Reflection and Learning

Composition studies scholar Kathleen Blake Yancey defines reflection as:

"...1) the processes by which we know what we have accomplished and by which we articulate that accomplishments and 2) the products of those processes (eg, as in, 'in a reflection')." As such, it is a "dialectical process by which we develop and achieve, first, specific goals for learning; second, strategies for reaching those goals; and third, means of determining whether or not we have met those goals or other goals" (Yancey 6).

Yancey's framing emphasizes the role of reflection in learning. We may also add that reflection involves the process of actively thinking about experiences and/or decisions, and is therefore a mode of inquiry (Taczak 2016). and typically involves asking questions. Furthermore, reflection is a learned, active skill.

Reflection for Students

The purpose of reflection is for self-learning and improvement – to learn about themselves and make sense of their experiences. Students who engage in reflection will become more self-direct/regulated learners. Reflection also helps students connect what they are doing and how it helps them learn.

Writing Effective Reflection Questions

- Write Open-Ended Questions

- Avoid question that could be answered with a Yes/No or one-word response.

- Poor Example: "Did you learn anything from the last project?"

- Better Example: "What did you learn from completing the last project, and how will that help you prepare for the next assignment?"

- Avoid question that could be answered with a Yes/No or one-word response.

- Try to Be Specific in Application.

- Student may struggle to answer questions that are too broad. To help them make learning connections, try identifying a heuristic or strategy with which you want them to be familiar.

- Poor Example: "How will you use what you learned in the future?"

- Better Example: "How might you apply audience analysis strategies to help you evaluate sources for the next project?"

- Student may struggle to answer questions that are too broad. To help them make learning connections, try identifying a heuristic or strategy with which you want them to be familiar.

- Focus on Relevant Content

- Asking students what they like or prefer isn't always relevant to their learning, and doing so can mistakenly frame their educational experience as one that needs to be easy, comfortable, and predictable.

- Poor Example: "What did you like about this assignment/reading?"

- Better Example: "What did you find most challenging about this assignment and how did you overcome that challenge?"

- Asking students what they like or prefer isn't always relevant to their learning, and doing so can mistakenly frame their educational experience as one that needs to be easy, comfortable, and predictable.

More example reflection questions based on the different learning and development domains.

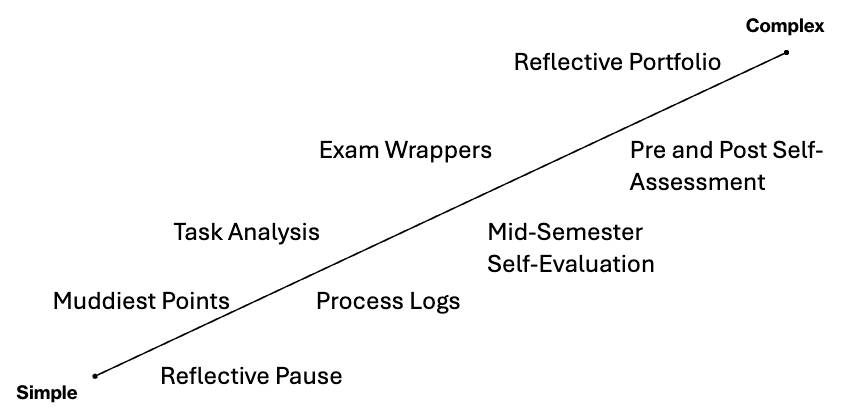

Examples of Reflection Activities

There are many types of reflection activities that can be adapted to different classrooms. For a full description of each activity view our Reflection Activities handout.

- Task Analysis

- Muddiest Points or One-Minute Paper

- Collaborative Troubleshooting

- Self-Reflective Comments on Draft

- Troubleshooting Journal

- Mid-Semester Self Evaluation

- Revision Memo

- Process Logs

- Exam Wrappers

- Transferrable Skills Discussion

- Project Post-Write

Tips for Talking to Students about Reflection

Provide rationale for the reflection activity or assignment. Why do you want to students to reflect? Here you can describe not just why they're reflecting, but how it helps them learn. No need to be coy here. Here are some example of what you could say:

- "I'm asking you to reflect on your choices in revising this draft because effective communicators are able to articulate their decision-making process. I want you to practice articulating your decisions."

- "We're spending time in class talking about how you might apply these strategies in the next project because I want to see your thinking."

- "Taking time to identify what worked or didn't work so well in your study approach can help you prepare more effectively for the next exam."

Common Questions about Reflection

Student’s motivation determines, directs, and sustains what they do to learn. Theories of motivation to pursue specific learning goals often focus on two factors (1) Value and (2) Expectancy (Lovett et al 2023). (1) A goal's importance, or subjective value, directly influences how people's behavior (or what goals they seek to obtain, based on their perceived value). For example, if a student does not find the content of a course interesting or relevant, they may see little to no value in learning the material. To help students see the subjective value of reflecting, instructors can explain the value of reflecting relative to students’ own interests. For example, if collaboration, you could ask students: “How might you use Wolf’s group writing strategy of a Team Contract in your GVSU student organization?” (2) While individuals typically need to find value in a goal to pursue it, they also are motivated to pursue outcomes they expect they can successfully achieve. For example, if a student doesn't think they can be successful in a Writing course, they will likely disengage from behaviors required for deep learning.

Another common way to think about motivation is through Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan 1985). According to Ambrose et all (2023), "grounded on the assumption that people inherently pursue growth and learning, self-determination theory suggests that students will find value when learning address three important needs" including autonomy, competence, and relatedness (92-33). In distinguishing between different needs and goals, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation emerge differentially. Intrinsic motivation deals with the satisfaction one gains by simply doing the task. Users typically already assign value to the content of the goal or activity. For example, if a student finds reading enjoyable and interesting, they are more likely to value reading, and thus more motivated to read for class. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation deals with the satisfaction one gains from a reward or doing something for a separate outcome (Ryan & Deci 2001). For instance, a student may choose to complete an extra credit assignment because they are extrinsically motivated by the extra points to improve their overall grade. Or a student may put more effort into a process reflection because they are motivated by the time it will save them completing a final project.

For more on strategies to improve student’s motivation, check out the Pew FTLC’s teaching guide on Motivation.

As faculty, consider what bias you may be introducing. Try using open-ended questions that encourage exploration in thinking rather than suggesting a certain answer. For instance, instead of: “Considering you did not perform well on this last exam, what do you think you need to do differently to earn a higher grade?” you might ask: “What did you do to prepare that helped you be successful? Why were those strategies helpful? Now that you’ve received feedback on your first exam, what might you differently?”

You may also avoid writing leading questions by eliminating inquiries about what students liked or disliked in an assignment, reading, class discussion, etc. E.g. “What was your favorite part of this assignment?” A more effective question to pose might be, “In this last assignment, what did you do well to support your learning?” This question could be even more specific by connecting the learning to a specific learning objective.

Transparency in expectations goes a long way. Clarify with students why you are asking them to reflect, and how that activity is connected to their learning. Students may be trying to please you because they don’t understand the task’s purpose or goal. If you’re concerned about using ChatGPT, talk to them about your concerns. Explain why you want to hear their thoughts because you’re interested in their learning process. Explicitly directing students to the learning goal or outcome can help students demystify some of the process. At the Pew FTLC we have a similar policy regarding the use of AI in Grant Applications:

“…we want faculty to engage in their own metacognitive thinking and reflect on their own experience./In other words, we are interested in your/originality of thought in applications and reflections. As readers, we want you to focus on the process, not the product” (FAQs – Grants).

You can also tailor the prompt so that it would be difficult for students to use ChatGPT. For example, if you are asking students to reflect on their process, require that they reference specific draft feedback from their peers or the instructor.

As for grade concerns, you might consider making reflections low stakes by reducing the number of points or weight or assessing the reflections on a 3–5-point scale. Concerns about grades often revolve around assessments being perceived as high stakes (e.g. a single assessment being worth 40% of their grade). To emphasize the importance of the learning process over product, structure the reflections so that if students miss one or two - or don’t provide what you consider to be a substance effort - it won’t tank their final grade.

Reflection for Faculty

Reflection for faculty, or "Reflective Teaching" is an important component of faculty development. For one, faculty are expected to self-assess their teaching as part of their institutional review process, so it's a good idea to practice this kind of metacognitive thinking. Institutional motivation aside, reflecting on your own practices can not only help you identify areas of success, but also opportunities for growth.

For example, after trying a new activity in class you may reflect on how it went. Were you able to accomplish your goals? Did students seem engaged? Would you do this activity again, and why or why not?

Additional Resources

Articles

Denton, A. W. (2018). The Use of a Reflective Learning Journal in an Introductory Statistics Course. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 17(1), 84–93.

Taczak, Kara. “Reflection is Critical for Writers’ Development.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Ed. Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle. Logan: Utah State UP, 2015. 78-81.

Taylor, D., Rogers, A. L., & Veal, W. R. (2009). Using Self-Reflection To Increase Science Process Skills in the General Chemistry Laboratory. Journal of Chemical Education, 86(3), 393.

Yancey, K. B. (1998). Getting beyond Exhaustion: Reflection, Self-Assessment, and Learning. The Clearing House, 72(1), 13–17.

Books

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Hartnell-Young, E., & Morriss, M. (2007). Digital Portfolios: Powerful Tools for Promoting Professional Growth and Reflection (2nd ed.). Sage. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/book/digital-portfolios

Shadiow, L. (2013). What our stories teach us: A guide to critical reflection for college faculty. Jossey-Bass, Wiley.

Yancey, K. B. (1998). Reflection In The Writing Classroom. Utah State University Press.

Webpages

Orlando, J. (2017, March 17). Reflective Learning through Journaling. The Teaching Professor.

Strategies for Deep and Lasting Learning: Questions for Reflection, Self-Assessment, and Discussion, Tyler Griffin, Teaching Professor Blog

"Cultivating Reflection and Metacognition" - Guide from The Sweetland Center for Writing at the University of Michigan

Bowen, J. (2013, August 22). Cognitive Wrappers: Using Metacognition and Reflection to Improve Learning. José Antonio Bowen.

Ways to Self-Assess Your Teaching, UCLA Center for Education Innovation and Learning in the Sciences