In a Haas Center for Performing Arts room, performers rehearsing for the musical revue “Side by Side by Sondheim” had just received their instructions for how they should move while singing the next number.

Sitting behind a keyboard at the front of the room, Josh Keller, the production’s music director, called out one last instruction: “Big breaths, y’all.”

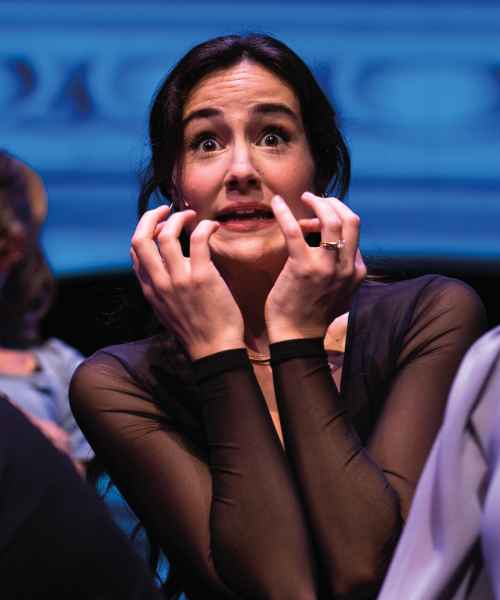

Keller sprinkled the rehearsal with reminders to take breaths at opportune times to maximize their singing output. Among the performers receiving the message was Joe Mayer, who was appearing in his fourth production for Grand Valley Opera Theatre and who along the way has learned something about the rigors of singing during a stage production.

(Valerie Hendrickson)

(photos by Valerie Hendrickson)

“Musical singing is a very different type of singing than classical recital singing — the way it sits in the voice and the tone that you use,” said Mayer, who is majoring in music education. “But also, running around and singing is a lot harder than standing next to a piano and singing Handel or something like that. It’s a very aerobic thing.

“I’ve built up stamina and now I can sing a recital with ease. It’s so much easier to breathe and to carry through a phrase and you have a better understanding of what you’re capable of when you do something like this.”

As an aspiring choir instructor, Mayer said these important lessons he learned about his voice in different performance settings have given him a solid base that will translate to his future career.

Helping students such as Mayer fully understand their artistry is at the heart of Dale Schriemer’s approach to developing their voice at the collegiate level. Schriemer, professor of voice and director of Grand Valley Opera Theatre, said his goal is for students to mature as artists and take ownership for how they express themselves.

“As a choir director, Joe will teach people how to perform. He has to understand the authenticity of his own experience,” Schriemer said. “The more self-informed students are and the more they understand their artistic process, the more successful they will be teaching that practice to another generation.”

One way Schriemer expands the voice abilities of his students is by choosing the work of challenging composers such as Stephen Sondheim. “Side by Side by Sondheim” contains an assortment of Sondheim’s complex songs from various musicals, which gave the students a formidable challenge to improve their performance skills, Schriemer said.

But in considering the continuum of students’ voice education while at Grand Valley, Schriemer said he takes a holistic approach that considers their emotions, their physical bodies, their spirit and their intellect.

“It’s very important for me that students understand that they are seen, heard and that they have agency,” Schriemer said.

“I’m not looking for obedience from students. I’m looking for a path forward.”

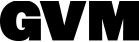

Elise Alvaro Dysart, who is pursuing a double major of music performance with a voice emphasis and advertising and public relations, has found her path forward as a performer. She said Schriemer has arranged for her to experience a wide range of music types.

“This has increased my depth as a performer and pushed me to blend and transfer my classical technique into entirely different styles of music,” Dysart said.

“I have sung opera, jazz, art song, musical theater and other styles that have stretched my abilities, deepened my knowledge of different vocal styles, shaped me into a more well-rounded performer, and furthered my skill as a vocal artist.”

As part of his instruction, Schriemer also wants to ensure students understand that their entire body is an instrument when singing.

That’s where Mr. Thrifty comes in.

The 3-foot skeleton — so named because it was the cheapest one Schriemer could find — allows Schriemer to show on the bony structure how respiration actually occurs, how the resonance is felt by the singer and how the whole unit creates the sound.

Color-coded anatomical drawings also help Schriemer explain the physical dimensions of singing. As Mayer can attest, singing requires intense physical exertion.

“When the entire physical being is coordinated in this effort, it looks so effortless,” Schriemer said. “The singer may be sweating, but the effect for the audience is a kind of smoothness and naturalness.”

Saying “It takes a village to raise great performers,” Schriemer credited the whole cadre of instructors and coaches who help students develop their voice and, ultimately, their confidence.

He also said outside experiences, such as the ones students receive working with industry professionals across the nation and abroad through the Linn Maxwell Keller Professional Vocalist Gift Fund, are critical for ensuring students are well-rounded as they leave Grand Valley.