The sky darkens and sirens blare as large chunks of hail batter the ground and the wind swirls, creating a funnel that has the potential to leave a path of destruction.

When a tornado occurs, the standard safety procedure is to take shelter, to run away from the storm. Ethan Mulnix, a junior majoring in geography, does the opposite: he runs toward the storm.

Mulnix has been fascinated with the how and why of severe weather systems, specifically tornadoes, since he was 4 years old. In high school, Mulnix began chasing storms more seriously, and now he serves as the vice president and department head of research for the global storm chasing team JWSevereWeather.

How did you first become interested in storm chasing?

When I was 4 years old, a tornado went through my backyard and ripped up an apple tree that I used to climb. Unfortunately, it also killed one of my dogs. Because of that, I wanted to know why and how these kinds of things happen.

When you were growing up, how would you investigate the weather?

Thank goodness for my parents and grandparents. They weren't fascinated with storms, but they would take me out on random trips when they knew a big storm was coming. Once when I was in high school, there was a chance for tornadoes in the Indiana-Kentucky area. I asked my mom, “Can I take the car and drive south and try to see some tornadoes?” She said no but after some begging, she finally said I could. That’s when I drove south and saw my first tornado. It was an EF-4. I’ve seen 65 tornadoes since that day, but I haven’t seen an EF-5 yet.

Talk about your storm chasing team, JWSevereWeather.

Jesse Walters and I co-founded the team in 2013, and it was purposed more for media and trying to get the word out to communities about severe weather threats.

Since then, we’ve developed five different focuses: research, education, media, immediate response, and search and rescue. We are a nonprofit organization, and we’re also a Weather-Ready Nation Ambassador™ through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That means within the U.S., we're certified to spread information that can protect people during potential severe weather situations.

Who are the members of the JWSevereWeather team?

Right now, we have 15 people all over the world. Three of us are in Michigan, including my brother. We'll collect data from the members of our team, and then Jesse and I will collaborate on how we'll go about tracking a system.

What was one of the scariest storms you found yourself in?

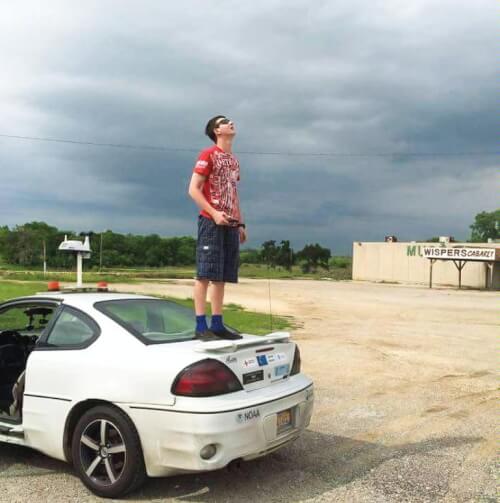

That would definitely be the Elmer, Oklahoma, tornado in 2015. I used my Pontiac Grand Am as my storm chasing vehicle, and it was equipped with weather instruments and a siren. The storm dropped about a mile-wide wedge on the ground near Elmer. I'm chasing it moving east and the tornado is moving in a northeastern direction, so I thought I would try to get in front of it.

As I was driving north, my radiator busted right in the path of the tornado. I tried to turn around, but the car kept overheating and turning off, and eventually it wouldn't turn back on. So, I'm sitting there with a mile-wide tornado to my west. The craziest moment was when the wind instruments measured about 113 mph and the car did a little shake toward the tornado, and then the tornado passed me slightly to the north.

Why do you keep chasing these storms when you know how dangerous they can be?

The research, really. My goal since high school has been to figure out what happens with tornadoes between the ground surface and 1,000 kilometers in the air. I want to know what's going on in the atmosphere that causes one super cell to produce a tornado while another super cell doesn't.

My team developed these tornado probes that we'll put inside tornadoes to measure wind speed, direction, pressure, humidity, temperature — all of the multiple factors that will help us understand how the tornado is forming.

I know what tools they used in the 1994 film “Twister,'’ but what do you use?

A lot of people think that our probes function like the ones in that movie, where they open up and send a bunch of tiny sensors up into a tornado. You can get equipment like that, but ours doesn't function that way. We do attach a Fly 360 Camera onto the top of one of our probes to get a 360-degree view inside of a tornado. One of our teammates used it during a 2016 tornado in Kansas, which was the first time anyone had captured a full 360-degree view inside of a tornado.

The sky is really my main tool, though, because you look out and try to figure out what's going on in the atmosphere around you. I also use the Radar Scope app, which is a live weather map that shows dots where other storm chasers are located. On my laptop, I have GRLevelX software, which shows a 3D model of what's happening inside of a storm. I have some instruments attached to my car that measure wind speed, direction and pressure, humidity, temperature, rain rate, and pretty much all of the essentials in the atmosphere.

What has been one of the neatest weather occurrences you've seen?

The twin tornadoes that occurred on June 16, 2014 in Pilger, Nebraska. That was actually my first chase out west. Just imagine two, twin EF-4 tornadoes dancing around each other, measuring 190 mile-per-hour winds, and then they do a little yo-yo effect and finally merge together. I was about a half-mile away when the tornadoes merged. That was by far the best event I've ever witnessed.

How can people benefit from your research?

Our research will help improve advance warning systems, especially in the U.S. All over the world, the most intense and damaging tornadoes happen in the Great Plains because all the necessary ingredients are there. There was a famous storm chaser named Tim Samaras who died in one of the 2013 tornadoes, but he was the first to put probes into tornadoes to collect new data. With that data, we've gone from 10 minutes to 17 minutes in advance lead time, and that's just from seven successful probes sent into a tornado. Now, imagine the kind of data we could gather to help improve advance warnings if we had 20 probes in a tornado.

What are your future plans with storm chasing and your education?

As long as I live, I plan to continue chasing storms. As for my education, I spoke with Elena Lioubimtseva, the current head of the Geography and Sustainable Planning Department, when I arrived at Grand Valley about what direction I could go with a geography degree. I didn't know this, but climate change can be a focus of a master's degree, so that might be a direction I go after Grand Valley.