Barney Boyer used to only care about how a fish tasted on a plate, then he began to study them.

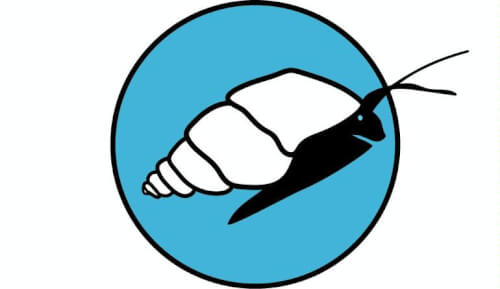

Boyer, a graduate student at Annis Water Resources Institute (AWRI), is studying the invasive mud snail, a pest with the potential to have a significant impact on several fisheries in the Great Lakes.

Even before he decided to study aquatic biology, fish played a big role in his original career choice. After high school and a three-year stint in the Air Force, Boyer followed a dream he shared with his brother to become a chef in his hometown of Chicago.

He went to culinary school, and worked his way up through the Chicago restaurant scene, ultimately ending up as a chef at Spiaggia, a Michelin-starred Italian restaurant. On several occasions, Boyer cooked for President Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle — he enjoyed the scallops — including the night after he won the 2008 election.

At the same time, a new trend in food was growing. Consumers started caring about the source of what was on their plate. The farm-to-table movement was born, and just eating a delicious dish wasn't enough for some consumers, Boyer said. So he started researching where his food was coming from.

"I got into environmental science because everyone was interested in where food came from, where it was raised, what the agricultural process was, how far it traveled, all of that," Boyer said. "I started looking into these things because I had to have an answer to give customers when they asked about the dish on their plate."

He researched everything from proteins to vegetables. He talked to farmers and dug into the local food system. He wasn't sure he liked what he found.

"I started to really wrap my mind around the impacts that we were having in the food industry," Boyer said. "I think that was when I really got interested in understanding what being a responsible consumer is."

Boyer took a hiatus from working in high-end kitchens, and began taking classes at a community college; he used G.I. Bill funding to earn a bachelor's degree in environmental science from the University of Illinois.

He joined the Veterans Conservation Corps, a division of the Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington state, where he studied Pacific Northwest salmon — some of the same fish that live in the Great Lakes commercial fishery.

Boyer said he conducted biomonitoring of salmon in the Snohomish River estuary along with other waterways and understood the importance of a healthy ecosystem to sustaining a viable population of fish.

"I wanted to be able to understand sourcing sustainable food sources, especially fish," Boyer said. "Fish is really the last wild animal protein source that people still eat — basically everything else is farmed now, and it caught my interest."

Boyer reached out to Mark Luttenton, associate dean of the Graduate School and an associate research scientist at AWRI, and asked about potential graduate student positions.

Boyer earned a graduate student slot and is hoping to use his research on the mud snail to help impact fisheries, which are multi-billion dollar aspects of the Great Lakes ecosystem.

"The mud snails proliferate really fast and take up large areas of the substrate on the river bottoms, and they consume a lot of algae and the like, which doesn't leave much room for other small invertebrates. That affects the food web," Boyer said. "How that affects cold water streams also impacts rivers, which are habitats for the salmon."

The mud snails he is studying are a formidable, if tiny, foe. Domestic mud snails are generally no larger than 8 millimeters, or the size of a small marble. But a single snail can produce 40 million snails in a year because they can clone themselves. Boyer said transferring snails is as easy as having one stuck to your boot and moving it to another watershed.

A long-term goal is to understand the impact of the snails and then down the line, how to work to solve the problem.

"This is my passion now. When I was younger, cooking was," Boyer said. "The more I learned about the impact of sustainability on food production, I felt like I had to jump in."