A History of Grand Valley State, 1958-2010

1958-1963

I. High Hopes

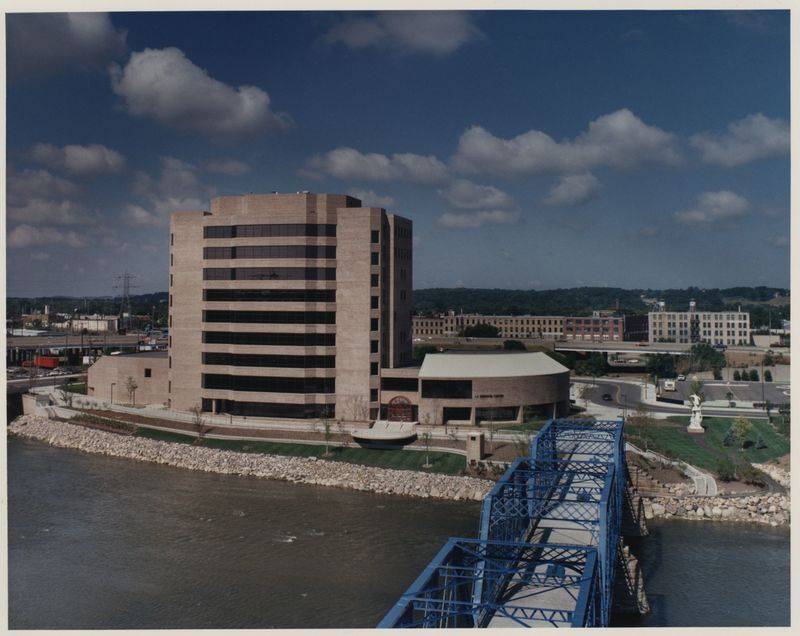

L. William Seidman, widely recognized as “the father of Grand Valley State University,” was interviewed for GVSU’s 50th Anniversary Video History Project shortly before his death in May of 2009. The Grand Rapids businessman, who became an economic advisor to Presidents Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, chair of the FDIC and head of the Resolution Trust Corp., among other national positions, recounted his attempts in the late 1950s to gain community support for a somewhat radical idea. He proposed to establish an independent, state-supported, four-year institution of higher education in West Michigan.

“We started having meetings with all kinds of organizations,” he remembered, “the labor unions, the various luncheon clubs, anybody that would listen to us … I would come in and I would take out what we used to call a recording machine, and I would play ‘High Hopes.’ You know, the song ‘High Hopes,’” he continued, describing Frank Sinatra’s Top 40 hit of the day, “the ant moving a rubber tree plant? Then we would tell them about this (college proposal) and ask them for their support. We did that for about a year. I must have gone to hundreds of meetings.”

Seidman and his team of community leaders had reason to set their hopes high. Following the end of World War II in 1945, the birth rate in the U.S. began to rise dramatically, peaking in 1957 with 4.3 million babies born, compared to an average of about 2.5 million per year in the decade before 1946. Those babies would begin to reach college age in the early 1960s.

Michigan legislators were anticipating the impending tsunami of baby-boom college students as well. Beginning in 1955, a succession of appointed congressional and citizen committees resulted in the hiring of Dr. John Russell, Chancellor and Executive Secretary of the New Mexico Board of Educational Finance, to direct a survey of higher education needs in Michigan. Fourteen publications resulted from Russell’s work, but the most important conclusions for West Michigan were identification of the area as “the most likely location for a new state-controlled college,” and the recommendation that a new institution of higher education be created, “with its own administrative organization, fiscal structure, and program of offerings.”

Thanks to the conclusions of the Russell Report, and the agreement by community leaders that it would be best to transcend rivalries, the option of an independent, state-supported, four-year college was soon adopted by almost all involved. L. William Seidman, a 37-year-old partner in the accounting firm established by his father, had been active in the earliest efforts to establish a new, local four-year college. In late October of 1958 he joined a group of nine other men, including both U of M and MSU alumni, to form the Committee to Establish a Four Year College (CEFYC).

GVSC founder and Board of Control member L. William Seidman. Seidman served on the Board from 1960-1974 and 1977-1983, is named first "honorary life member" of the board.

President Zumberge, John Russell, John Jamrich, and George Potter on the steps of Lake Michigan Hall. Russell and Jamrich wrote early studies that led to the establishment of Grand Valley.

The CEFYC, often meeting in one of Seidman’s favorite haunts, The Peach Nook at the Pantlind Hotel, was successful in attracting wide support for the proposed new college. Editorials and columns supporting the idea appeared in newspapers throughout the area, and by the beginning of 1959, more than 30 organizations had signed on in support. Preliminary work also had been done to establish a larger citizens committee to undertake the long process of making the project happen.

In February of 1959, Seidman and the CEFYC applied to the Grand Rapids Foundation for funds to collect data on the need for higher education in the area. $7500 was granted, with the stipulation that the study be under the direction of the Michigan legislature, and completed by the end of the year. Although no state funding was involved, it took four months of political wrangling to gain legislative approval. The CEFYC didn’t lose momentum during the process. They proceeded with identifying likely candidates for a Citizens Advisory Committee, and distributing 12,000 questionnaires to parents and students in second, tenth and twelfth grades.

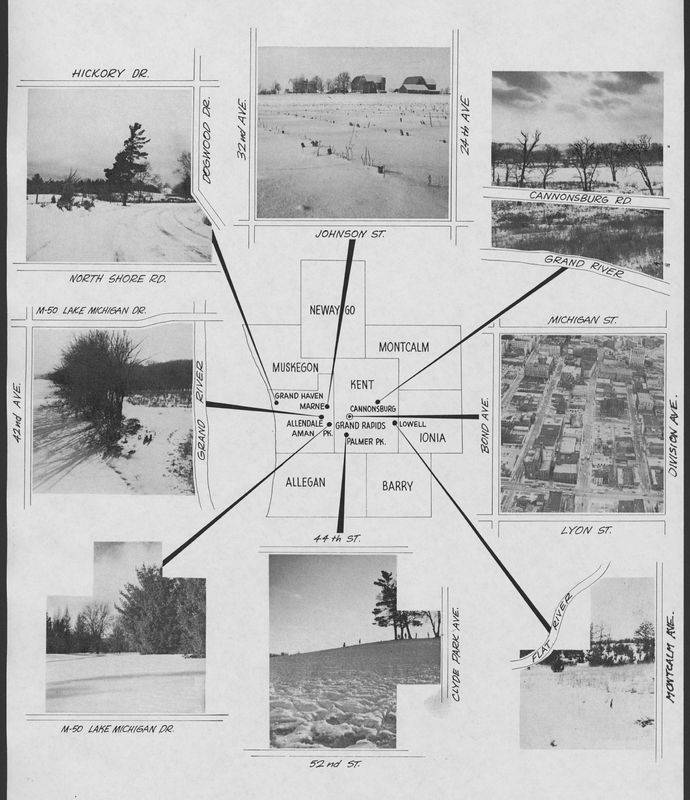

The House Resolution also required the appointment of a citizen’s advisory committee, “to assist, and to report its findings and recommendations to the 1960 Legislature.” Seidman and the CEFYC had been working since late 1958 to identify people in the 8-county area who would be most effective in realizing the dream of a new college. They solicited community leaders from labor, education, business and finance, service clubs, the farm bureau, PTAs, and many more, coming up with a group that included 52 from Kent County, 11 from Ottawa, seven from Muskegon, five from Allegan, three from Barry, four from Newaygo, and one from Montcalm. This group would not only help in the campaign to convince the legislature, and the West Michigan community, that the college was needed, they would provide the basis for the army of volunteers who brought the dream to reality.

II. High Aspirations

By the end of 1959, hopes were again soaring for the success of the fledgling college. At a November 30 meeting at the Peninsular Club in Grand Rapids, Jamrich presented his highly favorable report to 75 members of the Citizens Advisory Committee, area legislators and other invited guests. On December 30, The Grand Rapids Press ran a front-page, banner headline story reporting that Seidman expected to break ground for a new college in 1961.

But the community was ready to go. In September 1960 the Grand Rapids Press reported that the Grand Rapids Foundation pledged $50,000 to get the ball rolling. Before the Herculean task could begin, however, a legal entity to receive the donations had to be established.

Many buildings on Grand Valley’s Allendale campus are named for founding members of the Board of Control.

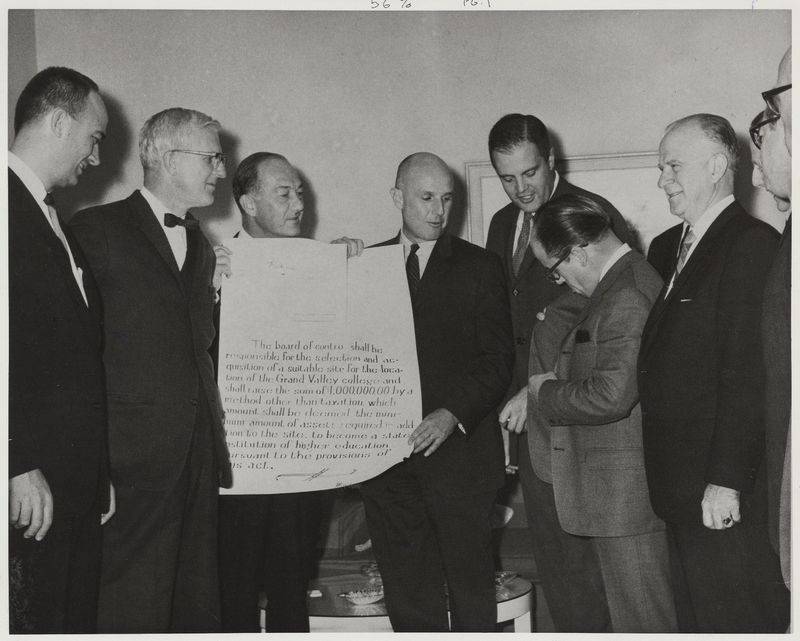

Governor G. Mennen Williams signing the bill that established Grand Valley State College as Michigan's 10th state-supported, four-year college on April 26, 1960.

Members of the first Board of Control: l to r back row-- Edward J. Frey, James Copeland, Dale Stafford, William Kirkpatrick, Icie Macy Hoobler, Kenneth Robinson. l to r front row--Arnold Ott, Grace Kistler, and L. William Seidman, Chair. The nine member board was later reduced to eight, 1960.

III. The Board of Control

In October of 1960, Governor Williams announced his selection for a nine-member Board of Control, as required in the legislation. Five had been recommended by Seidman and the CEFYC: Edward H. Frey, President of Union Bank of Michigan and the Grand Rapids Chamber of Commerce; Mrs. John Kistler of Grand Haven, former president of the Michigan Federation of Women’s Clubs and chair of the Adult Education Committee of the National Federation of Women’s Clubs; Dr. Arnold Ott of North Muskegon, President of Ott Chemical Co.; Dale Stafford, Editor and Publisher of the Greenville Daily News, and Seidman himself. Williams, with counsel from state and local democratic leaders, added Kenneth Robinson of Grand Rapids, Director of Region 1-D, AFL-CIO; James Copeland of Greenville, President of Security National Bank of Manistee and Wyoming State Bank in Kent County; Dr. Icie Macy Hoobler from Ann Arbor, a nationally recognized biochemist; and William Kirkpatrick of Kalamazoo, President of the Kalamazoo Paper Box Co. They were sworn in by G. Mennen Williams in his office in Lansing on October 17, 1960 and convened their first meeting there. Seidman was, according to the minutes, elected chairman by a “unanimous and enthusiastic” vote.

The Board moved quickly to establish the new entity. At a meeting in the home of Bill Seidman at the beginning of November, they planned a contest to name the new college, and accepted the donation of office space by Union Bank, at the corner of Pearl and Monroe in downtown Grand Rapids. On November 22 the Board met in their new office and appointed 109 members to the new Citizens Advisory Council, many of whom had already served on the former committee which advised the Jamrich study.

It also became clear that professional help was needed to begin organizing the new college. Bill Seidman had had conversations and correspondence with representatives from many of the state’s universities, and they were approached to loan administrators to assist in the initial planning of the college. In early 1961 Michigan State University, University of Michigan, Western Michigan University and Wayne State University, as well as Grand Rapids Junior College, all loaned consultants to help with planning while a search for administrators was conducted.

The Board agreed on the need to hire professional administrators to coordinate planning for many crucial areas. Fortuitously, at the same time, Dr. Chris DeYoung, Dean Emeritus of Illinois State Normal University, was living in Grand Rapids temporarily following his marriage to a local teacher. A native of Zeeland, Dr. DeYoung volunteered his services in late 1960 to help the fledgling college, and served as coordinator of the consultants team until April of 1961. He was compensated for his services by the Board at a later date.

A flurry of meetings, dinners, conferences, reports, recommendations, and correspondence in the first quarter of 1961 resulted in principles and suggestions for site selection, fundraising, president and faculty, curriculum and many other aspects of the new college that would have far-reaching effects that continue to be felt at Grand Valley State University fifty years later. (Exhaustive detailing of this process can be found in the Swets report, Chapter VI.)

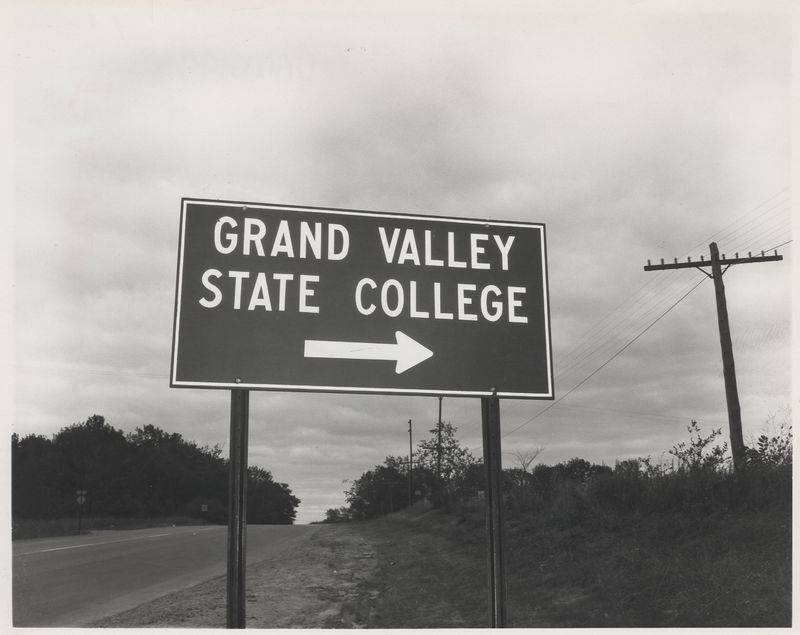

IV. A Place for Us

Even before the legislation enabling the new college was passed, rivalry for its potential location was heating up in the 8-county area. A committee had been appointed as early as 1959 to begin looking at potential campus sites, and area communities were quick to come forth with proposals and rationales for locating it within their boundaries. Grand Haven offered 150 acres of duneland along its north shore; even Whitehall, far north of the center of the 8-county area, came up with a proposed site in 1959.

The most serious early contender was a parcel of land donated to the city of Grand Rapids by Jacob Aman, who requested that it become a park. That was somewhat problematic, as the land on M-45 was several miles west of the city limits. Several city politicians saw the opportunity to turn it over to a new college as a solution. The issue became something of a football in city politics, however, while several other attractive proposals were floated. A group of enterprising citizens in Allendale, a small community about ten miles west of Grand Rapids, actually secured options on land along the Grand River they felt was supremely suitable for a campus. A Grand Rapids architect designed a 13-story “Tower of Learning,” to be located in the center city in an area slated for urban renewal. A group of Marne residents also were taking options on land near their community northwest of Grand Rapids, near what was to become Interstate 96, and Wyoming, southwest of the city, proposed a former industrial site.

In early 1961 the Board of Control appointed an official site selection committee of 36 members, chaired by Circuit Court Judge Fred N. Searl and Richard M. Gillett, executive vice-president of the trust division of Old Kent Bank and Trust Company. By February, 20 sites were under consideration, from Lowell to Muskegon, from Wyoming to Whitehall.

Map of original sites selected for the Grand Valley campus, published in the Grand Rapids Press, Jan 8, 1961.

The committee quickly narrowed the field. On February 15, 1961 they announced that they had chosen five finalists: Aman Park, Allendale, downtown Grand Rapids, Grand Haven, and Marne. Two communities scrambled to add their proposals after the deadline, Muskegon and Rockford, and the committee added them to the final consideration list. On March 10 the committee met to review its work to date. All sites had been visited and evaluated, and two were chosen as top contenders: Allendale and Marne.

Letters, telegrams, phone calls and petitions began to fly. The newspapers had a field day with recriminations and counter arguments. Backers of the Muskegon site were especially vehement, putting political, social, corporate and union contacts to work for their bid, and even taking their case to a committee of the Michigan legislature. But in the end, the central location of the Allendale site, unanimously recommended by the group of university consultants, as well as its physical beauty, won the day. Arnold Ott, the Board of Control member from Muskegon, told The Muskegon Chronicle that although he had been leaning toward the Marne location, after flying over the Allendale site he felt the “beauty of it could not be bought for a million dollars.”

On Friday, April 7, 1961, the Board met into the wee hours of the next morning considering the selection, and on April 8 at a public meeting at Grand Rapids Junior College, announced that the Allendale site had been chosen.

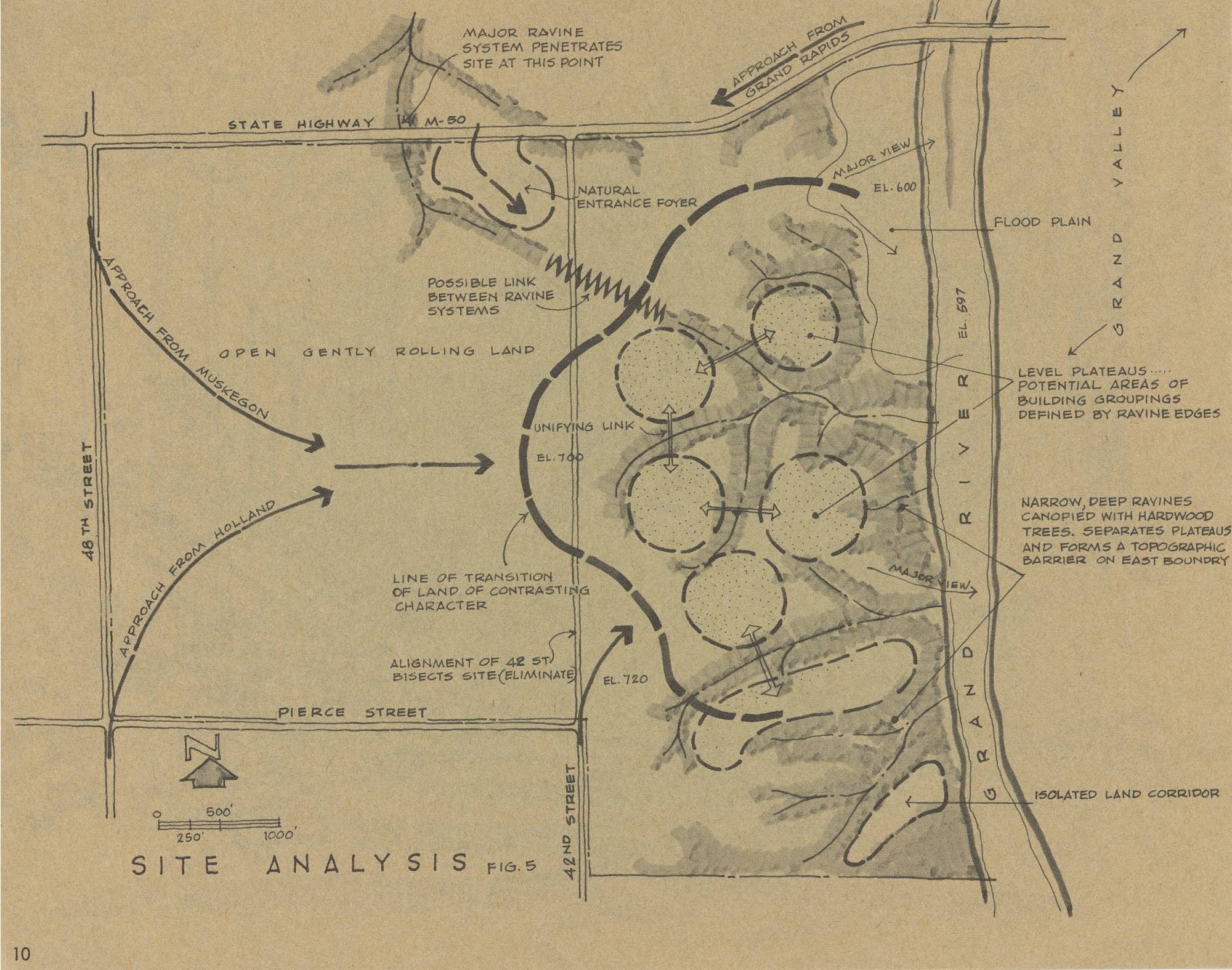

The 876-acre site on the Grand River once included Blendon’s Landing, a 19th century logging settlement long since vanished. Cut by ravines, the land slopes up sharply from the river, with several large areas of buildable terrain. The natural beauty of the campus would become a touchstone for the college community, even as, in decades to come, it began to expand into many of the areas which so hotly contested its initial selection.

V. A Name for Us

Although the legislation enabling the new institution of higher education for West Michigan refers to the entity as Grand Valley, there was not universal agreement that the somewhat bucolic moniker was suitable for the high aspirations of the new college. Bill Seidman, in correspondence cited in the Swets thesis, leaned toward something along the lines of Kent State, variations on the names of the constituent counties, or Michigan College at Grand Rapids.

At the meeting of the Board of Control in early November 1960, Greenville Daily News Editor and Publisher Dale Stafford was appointed to organize a contest among area schools to submit proposals for a new name. The prize offered was a four-year tuition scholarship to the new college.

By mid-January of 1961, more than 2500 entries had been received from approximately 1500 people. Among the most popular suggestions were: Wolverine State (59); Vandenberg (44); Wolverine (31); Wonderland (23); Great Lakes (19); Lakeland (16); Ko-mi-ban (many similar entries also were based on names of the area counties) (14); and 10 each for Arthur H. Vandenberg, Lake Michigan, Southwestern Michigan, Water Wonderland, and Western Michigan. Some suggestions had that mid-20th century ring of optimism: Learning for Life College, Bright Future, Bright Purpose, Bright Tomorrow, Dream Fulfilled, Paradise Gates, Peace, Utopia. Others set an idealistic academic tone: Athena, Cogito, Delphian, Octavo, Pallas Athene, Theta, Vade Mecum, Vale Vista.

In the end, nothing presented a more attractive alternative to the Board than the all-inclusive Grand Valley. In his Video History Project interview, Bill Seidman noted that "we decided we wanted a name that really sounded much more like an institution for the area that it was in."

GVSC Seal, 1960

Five people had submitted the name Grand Valley State College (a slight amendment to the HB 477 name Grand Valley College), so their entries were put in a hat and the winner selected. Frederick H. Brack of Grandville, age 20, was already a senior at Michigan State University. He designated his young sister Marianne Lovins, age 7, as the scholarship recipient, and in the fall of 1971 Marianne became a freshman at Grand Valley.

V. Million Dollar Mission Accomplished

The issues of site and name for the new college drew much public attention, but at the same time the more crucial issue of finance was being quietly pursued by some of the area's most influential movers and shakers.

The legislation enabling the new college in the spring of 1960 stipulated that a million dollar nest egg must first be raised, as well as funds for a campus site. Bill Seidman told The Grand Rapids Press in October of that year, "We are the only college to start with no assets and a million dollar debt."

At their second meeting, November 1, 1960, the Board of Control decided to organize the fund drive themselves instead of hiring professional consultants, and named Union Bank President Edward H. Frey as finance chair. Drawing on the strengths of their members, they also put Kenneth Robinson in charge of organizing support from the union community, and James Copeland was asked to establish the fundraising program in counties outside Kent County.

Much of the task for the group was to convince their peers in the area that the new college was necessary, and would be a good investment.

And there were some who needed convincing. There were objections on economic grounds by those opposed to increased taxation. Others questioned whether the state was obligated to provide higher education opportunities to students of limited academic accomplishment (a prominent Grand Rapids woman resigned from the CEFYC because of that belief). The Muskegon area, smarting from their unsuccessful bid to locate the campus there, was not forthcoming in financial support. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce president was quoted as saying the "so-called shortage" of college and university facilities existed only in the minds of those who wished to see the Federal government take over the responsibility of managing and financing higher education. Luckily, the Grand Rapids Chamber of Commerce, and its president, Edward Frey, were wholeheartedly in support of Grand Valley.

More than 5000 donors pitched in, with contributions ranging from $1 to $200,000. The Grand Rapids Press on April 29, 1961 announced that contributions from members of the Kent County Medical Society and the GR District of the Michigan State Nurses Association brought the total to $1,010,000. Along with generous individuals and businesses, many organizations collectively supported the effort, such as the United Auto Workers, the Michigan Education Association, and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). The Grand Rapids Foundation (now the Grand Rapids Community Foundation), made a mid-April contribution of $150,000, bringing their total participation in the effort to $200,000, more than eight times any grant they had to that date given any individual campaign. It matched another $200,000 gift that had been given anonymously.

Board of control members: Dave Dutcher, Phil Buchan, Ed Frey, Bill Seidman, Dick Gillett, Arnold Ott holding facsimile of GVSC mortgage. The group was about to celebrate paying off the mortgage by burning it.

Many individuals worked long and hard to raise the staggering sum. But, according to Swets, in conversations regarding the effort Bill Seidman strongly emphasized the role of Richard Gillett, by then Old Kent Bank President. "He just went out and got 25 of the best fundraisers in the community and went to work," he said.

The legislature's requirements had been met. Governor John Swainson had proposed funding the new college in his January budget message, and on June 2, 1961, signed a higher education appropriations act that provided $150,000 for operational funding for Grand Valley State College for fiscal year 1961-62.

Grand Valley was now a reality -- the first new four-year institution of higher education to be established in Michigan in 60 years. In his concluding section, Swets writes about the unique role of the new college. "Seidman … stated that they had done research on the establishment of new institutions of higher education in the U.S. and that they had been able to find no new college that had been established as GVSC had been established within a quarter of a century. There had been branch colleges and several municipal colleges, scores of community-junior colleges, many private colleges converted into state-supported colleges, but no new institutions such as this one. And this occurred in a community that has been labeled the stereotype of the arch-conservative, arch-reactionary community. Their success refuted the gloomy prophecies of local seers and seem to belie the statements made by those who had pointed to the inhibiting factor of a conservative or reactionary community."

Expectations for the new college were high. It was up to the hard-working group of supporters to take a deep breath, marshal their forces, and plunge into the next step: hiring a president and establishing a curriculum.

VII. The Right People; The Right Program

The Board of Control, as usual, was prepared to move immediately when their appropriation was approved. They named Philip Buchen as the first officer of Grand Valley State College, to serve as chief executive beginning July 1, 1961 while the search for a college president proceeded. Buchen, a law partner of U.S. Representative, and future president, Gerald Ford, had served the Board as volunteer attorney.

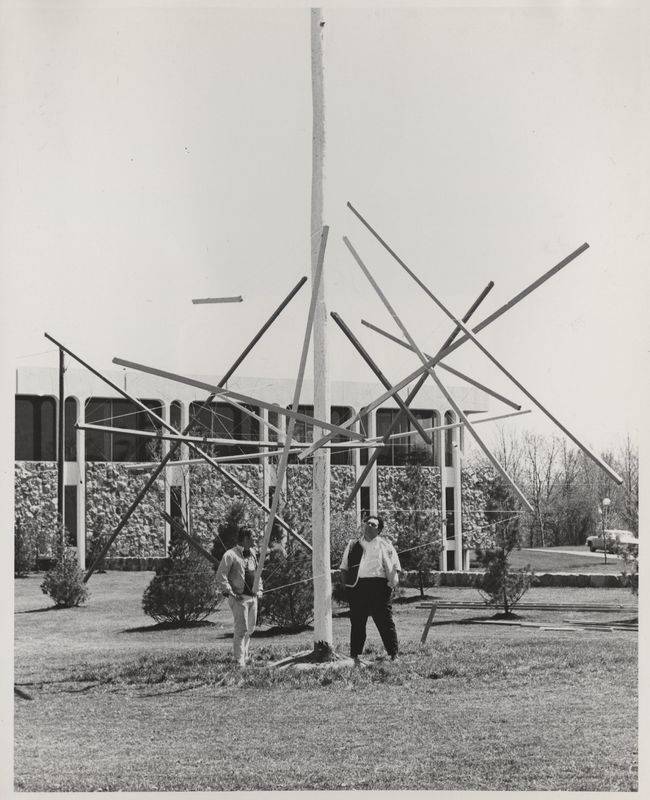

The Board also voted to purchase parcels on the Allendale site and to rent office space in the Manger Hotel on Michigan Street at Monroe in downtown Grand Rapids (later called the Randall House and then Olds Manor). The new office was "modernized with imaginative, unconventional methods that combine to give it a forward look," according to a Grand Rapids Press article July 27, 1961. This also included modernist sculpture and paintings, in keeping with the up-to-the-minute ideas envisioned for the new college. A furious debate in the newspaper's letters column about the merits of modern art ensued, foreshadowing the major role Grand Valley would come to play in the artistic life of West Michigan.

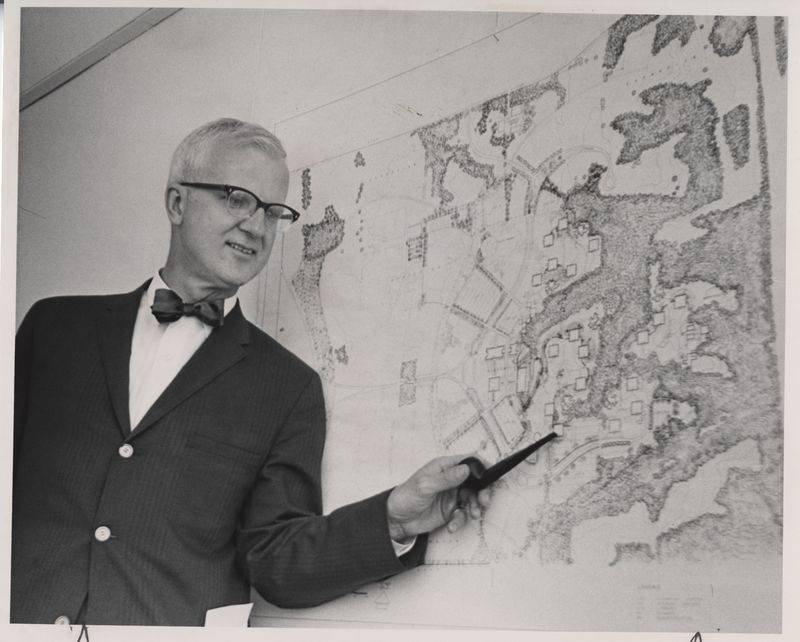

Philip W. Buchen reviews Grand Valley State College's Allendale campus map, 1963.

GVSC's first president, James H. Zumberge

Bill Seidman, Grace Kistler and Arnold Ott were appointed as a search committee charged with finding a president for the new college. A salary of $25,000 was proposed. A field of some 50 candidates was identified, and the position was first offered to a dean at the University of Michigan who had roots in West Michigan and had been assisting the Grand Valley group with curriculum planning. According to Bill Seidman, after Dr. Roger Heyns had accepted the job, he was offered another position he preferred (Heyns became Vice President of Academic Affairs at the University of Michigan in 1962 and Chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley in 1965). He asked to be released from his agreement with Grand Valley, and Seidman said that the stipulation they made was that he would assist them in continuing their search. Heyns was told, "We want to interview the top five candidates you have at the University of Michigan," Seidman remembered in his 2008 interview, "the ones you usually hide when recruiters come along."

Heyns complied, and in February of 1962 the first president of Grand Valley State College, James H. Zumberge, was appointed. A graduate of the University of Minnesota, Dr. Zumberge was a popular professor of geology at the University of Michigan and author of a widely used textbook. Only 38 years old, he had little experience in college administration. He was an internationally renowned geologist, and had led two expeditions to Antarctica, the first in 1957-58 during the International Geophysical Year, and a second two years later. Dr. Zumberge was appointed a delegate to the fifth IGY conference in Moscow in 1958, and a mountain in Antarctica was named for him.

One of the things that attracted the Board committee to Zumberge was his philosophy of education, closely aligned with the principles set out in the Russell and Jamrich reports. The new college would be targeted to a broad spectrum of potential students, and bold ideas about education would be embraced. In an interview with the Muskegon Chronicle, Zumberge said "We don't feel fettered by any previous program or system of ideas. We have to be bold in our moves and bold in our thinking, otherwise we'll be no different than the other nine state-supported schools."

Others in the West Michigan area were already agitating on behalf of their own bold, if somewhat retro, ideas. A group had formed, driven by the concerns mentioned above that providing higher education opportunities to students of limited academic accomplishment would not be a wise use of state tax dollars, and that it would dilute the prestige and tradition of excellence of a college degree. In July of 1961, the group, calling itself Grand Valley Citizens for a Better College, formulated ten principles which were published in The Grand Rapids Press, among them liberal education, enduring truths, intellectual discipline, and avoidance of vocationalism and highly commercialized programs of athletics.

Prominent in the movement to define the new school's focus, and a member of the citizens' group, was William Harry Jellema, founder in 1921 of the Department of Philosophy at Calvin College in Grand Rapids. He later chaired the same department at the University of Indiana, but returned to Calvin and retired at the mandatory age of 70 in 1963. He was hired first as a consultant to Grand Valley, and then as its first faculty member.

Jon Jellema, the son of Harry Jellema, joined Grand Valley's English faculty in 1972 and became Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs in 2005. In an article about Grand Valley Presidents in the Winter 2007 issue of Grand Valley Review, he wrote that, "Zumberge's strong credentials and academic reputation lent instant credibility to the foundling institution and helped attract a strong, albeit not very diverse, group of faculty."

In an article for the Fall 1995 GV Review, Dewey Hoitenga, who became a professor in the philosophy department at Grand Valley in 1965, quotes a letter written by Zumberge to Jellema's family at his death in 1982. "Harry Jellema began his second academic career at GVSC when he became the first professor that I engaged for the new college. He was the reason that we were able to field an unusually good faculty of fifteen to start things going. His presence set the level of quality that I was looking for."

William Harry Jellema

Vice President George Potter

Whether one or the other was more influential in the academic foundation of the new college, Zumberge and Jellema were definitely a powerhouse duo. Along with Bill Seidman, the fourth person to have a profound effect on the development of Grand Valley's first curriculum was George Potter. A graduate of Oxford University's Oriel College, founded in 1326, Potter was a strong advocate for the collegiate societies formed in venerable English universities, emphasizing a common curriculum of classic liberal arts. Potter was hired as President's Assistant for Academic Affairs in 1962, and became Grand Valley's first Vice President of Academic Affairs in 1966.

In a report written by Zumberge in 1964 describing the formative years of Grand Valley, he gives an account of a meeting he convened in June 1962 at Hidden Valley, a private club in northern Michigan. The weekend curriculum conference included Zumberge, Seidman, Jellema, and Potter, as well as Buchen, Grand Valley's new librarian Stephen Ford, and consultants from Michigan State University and the University of Michigan. Their goal for the weekend was to answer one question: what shall be the freshman program of instruction at GVSC? The pressing need was to produce a catalog with defined course offerings to begin recruiting faculty and students. The decisions made that weekend would have far-reaching consequences for the fledgling college.

The group decided to establish a foundation program in which all entering freshmen would be required to take nine courses, three each in the three 11-week quarters of the academic year. Each course would carry five credits, and students would also take a non-credit course in physical education. The proposed curriculum included courses such as History of Greece and Rome, Introduction to Moral Philosophy, Problems of Modern American Society, Frontiers of Science, and Foreign Languages 1 and 2, with choice of French, German or Russian. (The complete listing can be found on p. 14 of the Zumberge Report). Grand Valley would be strongly committed to undergraduate education and avoid the professional schools and graduate programs that dominated other regional universities.

Dr. Anthony Travis, who joined the Grand Valley History faculty in 1971, has written extensively about the college's early years. In an essay for the Grand Valley Review Fall 1995 titled "Community Pragmatism vs. Academic Foundationalism: The Beginnings of GVSU," he traces developments in American higher education across two centuries, and the conflict between those who were committed to a 19th-century classic liberal arts college model and the more contemporary idea that tax-supported institutions had a responsibility to the community to provide professional education in areas such as business and education. "The first ten years of Grand Valley State College … were dominated by two philosophical paradigms that competed to test which would form the academic culture of the new institution," he wrote. "The first of these I have termed 'community pragmatism' and the other 'academic foundationalism.' During the first ten years of (GVSC) these two educational philosophies were in creative tension."

There was another conflict for the idealistic group who were urging the latter model. They were under a mandate from the state legislature to keep costs low and enrollment high. The curriculum they proposed required intensive faculty-student contact, with small group discussions and tutorials in the classical education vein as the hallmark of the institution.

A definitely modern solution was proposed for the dilemma of how to inexpensively provide a faculty-intensive program to a large number of students. Bill Seidman had become interested in the earliest stirrings of information technology. He proposed an innovative system of audio-visual study carrels. Professors could tape their lectures and other materials, and students could dial up the tapes in individual carrels, greatly increasing the efficiency of student-teacher ratios.

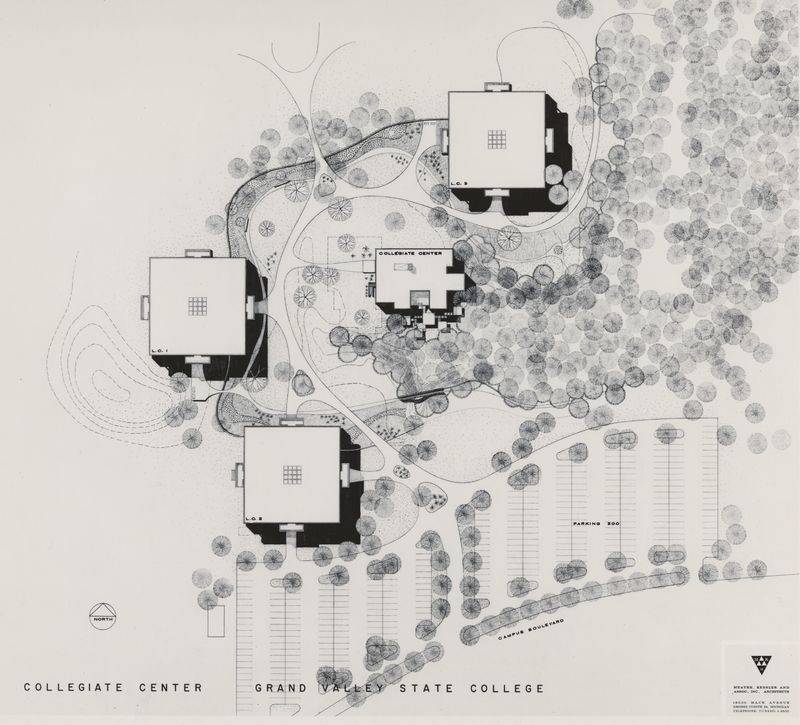

The expectation of large enrollments also presented a problem for the planned curriculum of individualized liberal arts education. George Potter, drawing on his experiences with small, relatively autonomous college societies within England's large major universities, designed a system in which new academic complexes would be created for every 500 students admitted to the college (later increased to 1500 students). They would share common facilities such as the library and science labs. The decentralization plan set the stage for what would become Grand Valley's famous cluster college era.

The decisions made that weekend about curriculum and campus organization would not only inform Grand Valley's development to this day, the vision of the group would find physical form in the architecture being conceived for the Allendale site.

VIII. Breaking Ground

The idea that the physical structure of the new campus site and buildings was integrally tied to the academic vision was evident in the decision made in September 1961 by the Grand Valley Board to hire the newly formed firm of Johnson, Johnson and Roy of Ann Arbor as chief consultants for site planning of the new campus.

The firm's principals included a landscape architecture professor at the University of Michigan, William Johnson; his brother Carl, and Clarence Roy, both practicing landscape architects. In a 2003 monograph about the firm, which became JJR, author Fiona Gruber quoted William Johnson in a statement of the firm's philosophy that still resonates on the Grand Valley campus today. "In most cases, the leading element shaping community is thought to be architecture, while open space is relegated to a secondary role. Properly understood and crafted, open space can often assume a primary position, well before building programs are defined. Open space can form the basis for a development strategy."

The firm moved quickly to propose a site plan that emphasized the deep wooded ravines and narrow plateaus of the campus overlooking the Grand River. James Zumberge, in his 1964 President's Report on the formation of Grand Valley, wrote that the firm had just one directive: that the planned academic program would be best served by groups of small general purpose buildings. "The site planners used a distinctive feature of the campus terrain to achieve the … objective," he explained. "Each plateau is ideally suited for the building of two clusters of general purpose academic structures constituting one of the collegiate units of the master plan."

Site analysis map, circa 1961. The map, labeled as Figure 5 of the publication, features a site analysis of the landscape located west of the Grand River and south of State Highway M-50 (later designated M-45), including the topographic barrier created by the ravines and the plateau areas for potential campus building groupings along the edges of the ravines.

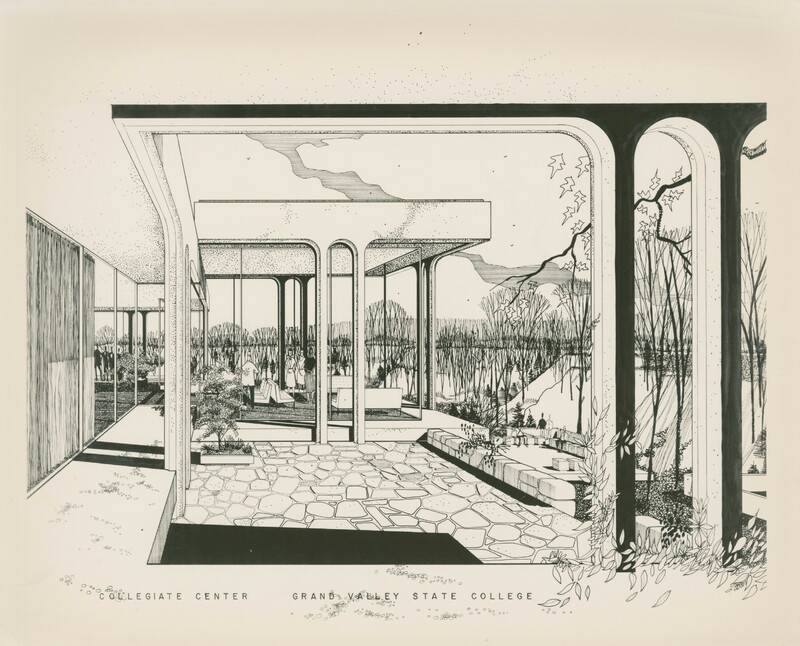

Architect's drawing of the interior and exterior of the Collegiate Center of Grand Valley State College, later named Seidman House, circa 1962. In the drawing, the study lounge and outdoor terrace of the Collegiate Center are featured among the wooded ravines, with people seen inside the windows of the building and outside enjoying the outdoor patio seating.

In November of 1961, the Board selected architects Meathe, Kessler & Associates of Grosse Pointe to design the college's first buildings. They were confirmed at the December 15 meeting, and within a week, William Kessler and Carl Johnson had set up a design shop in one of the old farmhouses on the Allendale site, spending hours walking the land and staying in a nearby motel.

It was an exciting time for architecture, mirroring the enthusiasm and drive of the era of President John F. Kennedy and the post-war confidence of America. William Kessler had been a student of Bauhaus icon Walter Gropius at Harvard, and had been attracted to Michigan, along with Philip Meathe, to join the firm of noted Detroit iconoclast Minoru Yamasaki. They were a part of a movement to transcend the international modernist style that had produced a popular backlash against mathematical, sterile exercises in concrete and glass. Their designs for Grand Valley's first buildings reflected new concepts about flexible space, interaction with the environment, and innovative use of materials and technology.

The plans for the new college's first buildings incorporated upright arched supporting columns made of cast concrete that came to be known as "concrete trees". Masonry walls between the columns were to be faced with split Michigan fieldstone, adding to the impression of living structures growing from the ravine-edge landscape.

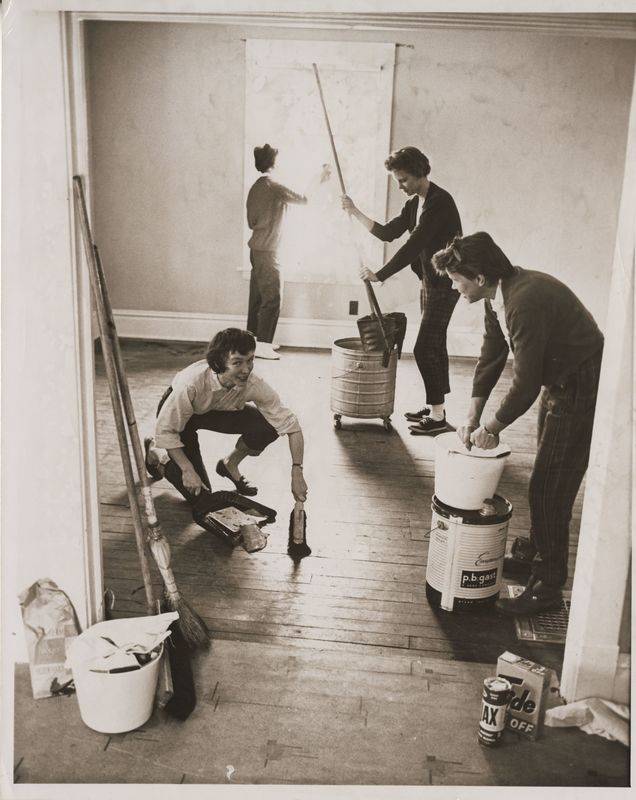

In the spring of 1962, Grand Valley was asked to vacate its downtown Grand Rapids offices in the building which was slated to become Olds Manor senior housing. An army of volunteers -- cleaners, painter, plumbers -- descended on one of the old farmhouses on the Allendale campus to transform it into a new campus office. The college's Public Relations director, Nancy Bryant, and buildings and grounds superintendent Don Lautenbach, even planted a vegetable garden behind the old farmhouse, foreshadowing the renewed interest in local food that is sweeping the campus as it celebrates its 50th anniversary.

All the pieces were in place for the new college officially to break ground. On August 28, 1962, dignitaries gathered for the ceremony. Thoughtful and idealistic speeches were made, including James Zumberge's description of the design of the new buildings as "the marriage of the bride of beauty with the groom of function." Governor John B. Swainson hit the button to trigger a dynamite blast to break the ground, literally, at the site of the first new building. Nothing happened. He hit it again, and again nothing. In the archives of Grand Valley is a file of memos from Zumberge preparing for the event, including a detailed back-up plan for thoroughly cleaning out a barn to be used in case of rain. But there was no back-up plan for the failure of detonation. After a half-dozen tries, the Governor good-naturedly gave up. Master of Ceremonies David Dutcher announced, "Let us consider the ground broken," and proceeded with bringing the august occasion to a close. As the spectators and participants were dispersing, the dynamite finally ignited with a stupendous blast, prompting cheers from the crowd and signaling an auspicious beginning for Grand Valley's new home.

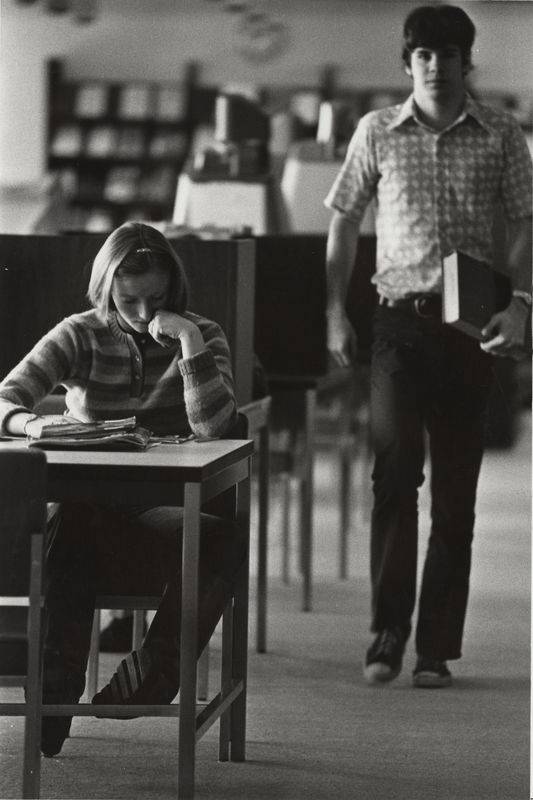

IX. Let the Learning Begin

Although there were some other glitches in the construction process (as was and ever shall be), including delayed bond sales and ill-timed workers' strikes, the stage was set for the first students to arrive at Grand Valley State College in the fall of 1963.

In the first brochure developed to describe the new college, the prospective student body was characterized: "The college will be searching for able surprises -- students with a talent for creativity who give promise of rising to the challenge of an imaginative college program."

That description might also have served for the men and women brought to remote Allendale to teach these "able surprises." In his 1964 Report of the President, Zumberge described the first faculty hires. "They saw an opportunity to participate in building a sound academic program in an atmosphere unshackled by tradition and unhampered by an existing 'old guard' faculty," he wrote. "That the first GVSC faculty looked for such opportunity is, in itself, an indication of the caliber of people who were attracted by our fledgling school. They realized that their contributions to the success of the college would be important."

Glenn Niemeyer, who would become one of Grand Valley's longest-serving academics, remembered his arrival in a 2008 Video History Project interview. With a just-earned doctorate in history from Michigan State, he said there were many openings for faculty across the country, many new and experimental ideas in education. But Grand Valley offered something else that attracted him, "the opportunity to craft a history curriculum … There was a kind of excitement," he remembered, "the fact that we were beginning a university."

In the fall of 1962, the first students were accepted and enrolled. It was not an easy task for the small staff charged with recruiting them. "Because GVSC was established to fill a need created by more students clamoring for a college education," Zumberge wrote in his 1964 Report, "it is paradoxical that we were not deluged with applications. But there was a reason for it. Students who could afford to go away from home to college were not likely to list Grand Valley as their first choice. And most students who could not afford to go away to school were inclined to select an institution of established reputation in the area before taking a chance on a new, non-accredited college whose physical plant was still on paper."

Cleaning Grey House, the location of the first campus administrative offices at Grand Valley State College, 1962.

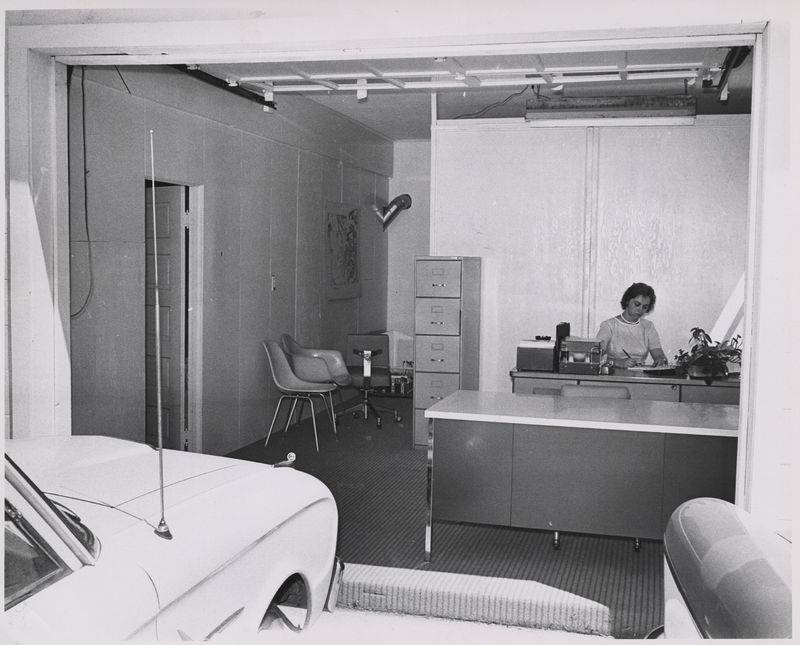

First administrative office in former garage of one of the original buildings called the Pink House.

Zumberge and his tiny admissions staff canvassed the area's high schools, attending College Night programs, talking to parents and potential students. He embarked on a vigorous fundraising program to establish tuition scholarships, and solicited letters from the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and Wayne State University stating that they would accept GVSC credits in transfers, prior to accreditation. He even hosted luncheons for high school counselors and principals, "hammering away," as he put it in his report, "at the virtues of the tutorial system." He concluded that it was this feature that finally won the sympathy and support of the counselors.

"My friends thought I was a little crazy," said Diane Paton in her 2008 Video History Project interview. Then Diane Hatch, she was the first accepted applicant to enroll at the new college. She describes being picked up in the college's VW bus with friends from Muskegon High School for a tour of the campus, which at the time was just a model on a table in a farmhouse, in the middle of cornfields.

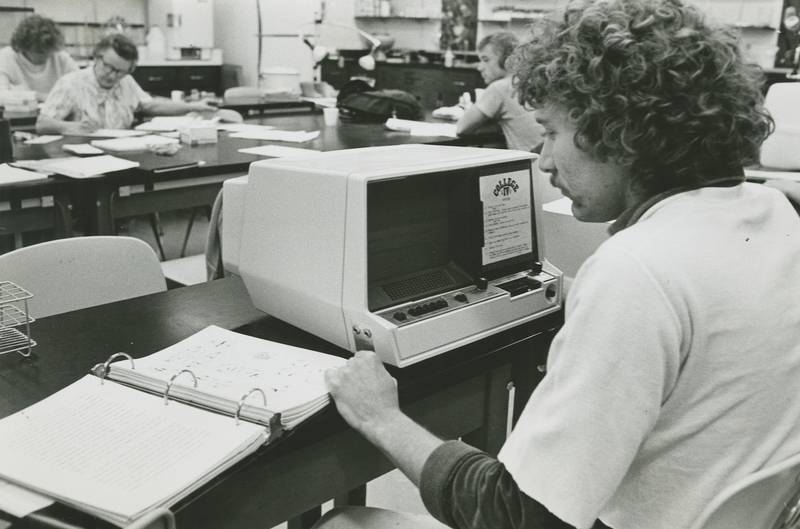

By the fall of 1962, several dozen pioneer freshman had been registered in a garage on Lake Michigan Drive. The surroundings may have been improvised, but the college continued its innovative approach by becoming one of the first in Michigan to employ IBM's new punch-card computer technology to register students. After a winter notable for very cold weather and heavy snow, and a flurry of construction in the spring and summer, the new college was ready (just) to open in September, 1963.

X. A College in the Cornfields

In May, 1963, the first faculty meeting was held in the Allendale Township hall. With only 15 faculty members in 11 different subjects, the group organized informally into three divisions: humanities, social sciences, and sciences. None of the technology that was planned to assist in the faculty-intensive teaching program was ready for use, but the group agreed to the outline developed in the earlier curriculum sessions. Students would meet in large lecture groups of 90-100, break into smaller discussion groups of 10-20, and meet with professors for tutorial sessions of no more than 3-5.

By the end of the summer, more than 200 students had enrolled, and in August the college threw them a welcoming party, a "hootenanny," according to Diane Paton, including singing, hayrides and a barbeque.

Hootenanny "Free For All" held for incoming students on the first day of classes, 1963

Board member William Seidman speaks at opening day ceremony, 1963.

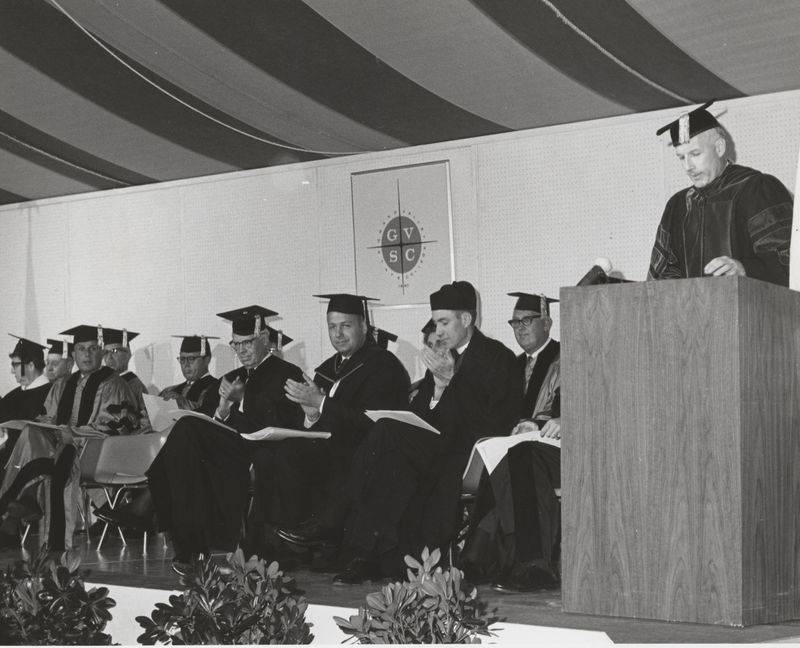

A more solemn, if somewhat steamy, atmosphere pervaded the second floor of the theoretically air-conditioned Lake Michigan Hall on September 26, 1963. Opening ceremonies for Grand Valley State College assembled students, faculty in academic robes, parents, donors, and members of the Board of Control in what was the dining room for the college. "No event such as this had occurred in Michigan for nearly sixty years," wrote Zumberge in his 1964 report, "and we all felt at once a deep sense of humility and exhilaration at the thought of being part of this important endeavor."

Because of the problems with weather and construction delays, only Lake Michigan Hall was completed to welcome the 226 members of the pioneer class. But, ever plucky, all made do with what was at hand. The library, which had been a priority for the new President, was on its way well before opening day to establishing an impressive collection. Head Librarian Stephen Ford had been working on acquiring books for over a year, operating out of a small private house on the campus site. By the time they moved into temporary headquarters in Lake Michigan Hall, a staff of seven had been appointed and nearly 10,000 books had been catalogued. Business and administrative offices remained in the remodeled farmhouse, and faculty members doubled up in makeshift office space. Some of the problems were alleviated at the beginning of winter quarter, when Lake Superior Hall was completed in time for occupancy right after the Christmas recess.

The pioneer class rose to the challenge of creating student life on the new campus. A student government was formed and a student charter drafted. Physical Education, a requirement in the curriculum, was limited to outdoor track activities and shooting baskets in the hayloft of one of the old barns. A few showers were installed in one of the farmhouses. But the seeds of Grand Valley's longest running sport were sown before opening day, when racing shells for the rowing competition known as crew were purchased with a fund organized for that purpose by Grand Rapids businessman Mike Keeler. A crew house, nicknamed "Muscle & Corpuscle," opened in November and athletes began to train for what would become the college's debut in national intercollegiate competition. During the winter a ski club made use of the rolling terrain of the riverside campus, and a variety of inter-mural games were organized.

Also in November, the first student newspaper, The Keystone, published its first edition. Editor Elaine Rosendall wrote, "This is your paper; not the theorizing tool of the faculty." President Zumberge added a column enumerating his conception of the role of student newspapers, describing it as a "...forum for expression of student opinion and editorial comment." Somewhat presciently, if erroneously, considering events five years later, he concluded, "It is in this last role where many newspapers published by college students eventually end up at odds with the administration, faculty, townspeople, and parents. I don't think this is inevitable, however."

College administrators holding racing shell as rowing is initiated as the first sport offered by Grand Valley.

Grand Valley State College was on its way. In August 1963, a foundation had been established to receive gifts, donations and bequests for the benefit of the new college with Richard Gillett as its first president. The Loutit Foundation of Grand Haven contributed $300,000 to help construct a science building, the college's most significant gift to date and beginning a tradition of community support for growth that was to help the new college blossom over the next 50 years.

But not before some intense growing pains, and radical rethinking of almost every initial premise the founders had developed. The times, as one bard so famously put it, they were a'changing.

1964-1969

I. High Anxiety

"There is no question that the original academic program of Grand Valley College was a good one in theory. There was only one thing wrong with it: not very many students found it appealing."

Everything seemed to be going well as Grand Valley State College's pioneer class came to the end of its first academic year. Despite a sea of mud and the constant clamor of construction, there was a palpable sense of pride in being part of an innovative and creative new institution that was drawing national attention.

The November 1964 issue of Fortune magazine cited five new campuses in the U.S. chosen "because their superior architecture and design seem best to anticipate the kind of educational world they will serve." In the section about Grand Valley, titled "Self-Reliance Near Grand Rapids," the article dubbed it "a brand-new college, not just a new campus for an old college," praising it as "handsomely designed to fit its unique setting," and enthusing about its "latest teaching devices," which, they said, would "encourage the students' self-reliance and avoid overdependency on formal instruction."

In November 1966, Architectural Record ran a large section about the designs of Meathe, Kessler which prominently featured their work for Grand Valley. Interiors magazine featured the school in December 1964, and in September 1965 College and University Business ran a long cover story about Grand Valley's educational philosophy and the design of its first group of buildings.

Architect's plan of the Great Lakes Group with the Collegiate Center (later Seidman House), and Learning Centers (LC1) Lake Superior Hall, (LC2) Lake Michigan Hall, and (LC3) Lake Huron Hall by architects Meathe, Kessler & Associates, 1962.

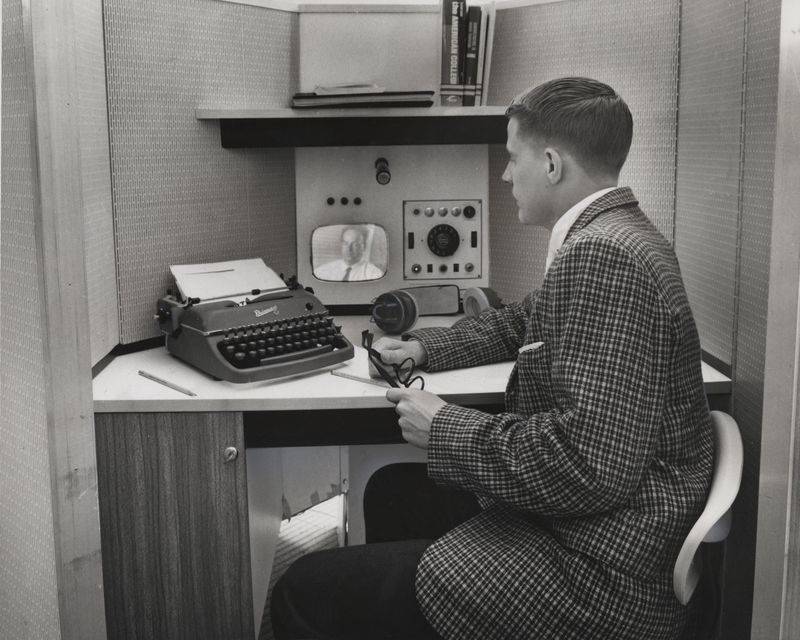

Student using audio-visual services at a sound-protected study carrel. The carrel is equipped with headphones, a microphone, video screen, and a typewriter, ca. 1964.

The innovative technology envisioned for Grand Valley had also drawn national press attention. The August 1963 issue of Architectural Forum had a special issue focusing on "Plug-In Schools." Grand Valley was called a "radically new kind of facility: the learning center." The school's carrels and audio-visual system were described as "instant access through the twirl of a telephone dial." An article in The New York Times on September 5, 1965 noted that "Students at Grand Valley State College … are at work on experimental Astra-Carrels, made by the American Seating Company."

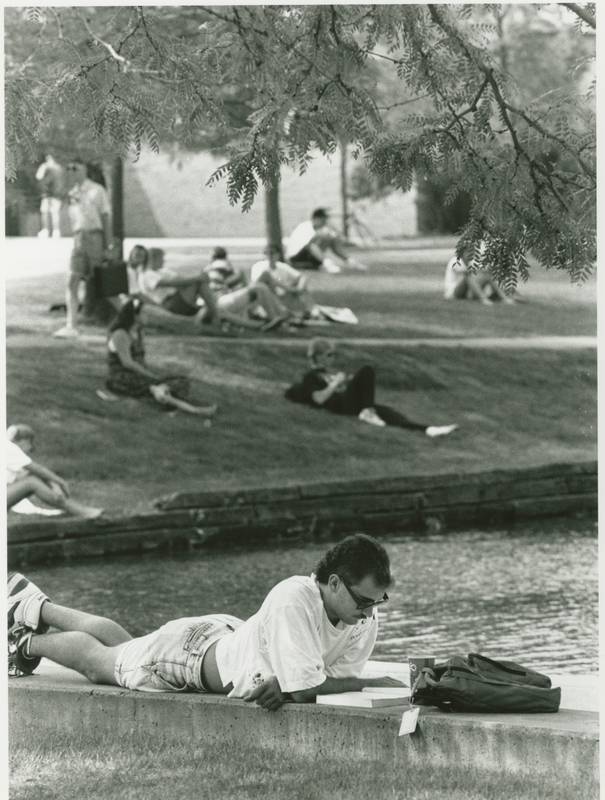

Meanwhile, back in Allendale, the Grand Valley campus was growing by leaps and bounds. The Great Lakes Group of classroom buildings, including Lake Michigan, Lake Superior and Lake Huron Halls were open, as well as Seidman House, which provided space for a student center, bookstore, and offices for student groups. The Little Mac Bridge was dedicated in September 1965, connecting the north and south areas of campus and opening access to the site of the college's first residence hall, Copeland House, and the Loutit Hall of Science. By the end of August, 1966, work was progressing on seven buildings, including a domed fieldhouse.

By the fall term of 1966, however, it was becoming clear that some things were not proceeding according to plan. Projections for enrollment that fall had been in the neighborhood of 1,800; only 1,340 students had registered. Earlier that summer, The Grand Rapids Press ran a stinging feature about problems at the new college, suggesting that Grand Valley "rushed into operation" and that enrollment predictions had been "wildly optimistic." Because admissions were slow, the article reported, the college had accepted two of every three students who applied, resulting in a student body that had been cited in an early visit by an accreditation team from the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools (NCA) as the school's "weakest link."

The administration were not unaware of the factors that hampered the college's appeal. In the fall of 1965, programs in teacher training and business administration had been added to the curriculum, over the objections of some who cherished the pure liberal arts dream of the founders. And some conditions that had pushed the creation of new colleges in Michigan had changed. In his 1969 report, "Grand Valley State College: Its Developmental Years 1964-68," President Zumberge wrote that once the recession of the late 1950s was over, parents could afford to send their students to colleges away from home. "On the very day it opened," he explained, "GVSC was in a buyer's market instead of a seller's market, exactly the opposite of what the experts had predicted."

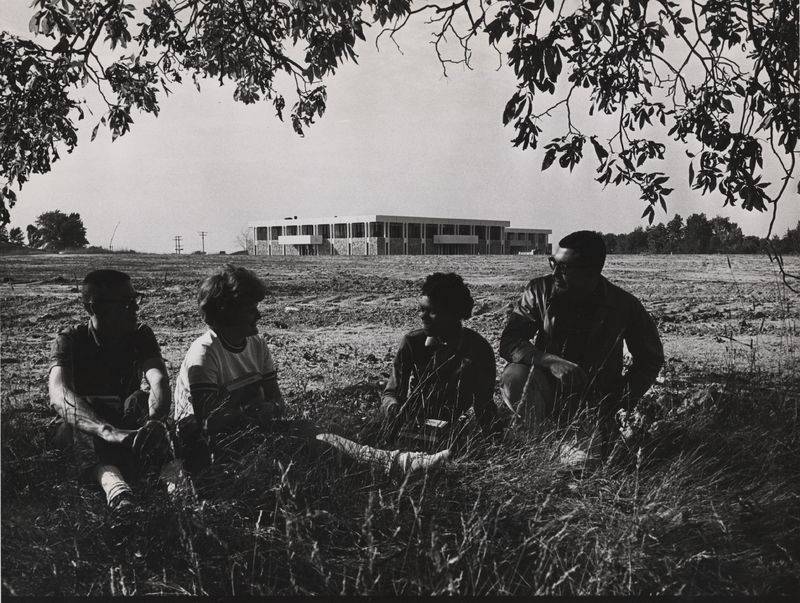

Students seated in a field on the GVSC Allendale Campus, 1960s.

Grand Valley also was facing a high drop-out rate. In surveys completed by students who were eligible to return but didn’t, two issues stood out: a limited academic program with demanding foundation requirements, and the lack of social life on campus. Although the college had abandoned the idea of remaining a commuter college and was constructing housing for students as quickly as possible, there was very little to occupy students outside class time. Allendale offered only a bowling alley, and Grand Rapids was a long drive away for an evening's diversion. In the Grand Valley Review of 1995, which featured essays about the college's history, Math and Statistics Professor Donald VanderJagt, who came to Grand Valley in 1964, dryly commented, "The regular sight of herds of cows and sometimes herds of deer on campus was simply not sufficient to satisfy the extracurricular needs of the students." In the early spring of 1965, four students were fined and two suspended in "Grand Valley's first panty raid."

More seriously, leaders of the new college realized that one factor crucial to attracting top-notch students was accreditation from NCA, the largest of the five regional accrediting associations for higher education in the country. The process includes detailed internal study by the institution, along with examination by a team of peers.

Zumberge first made contact with NCA in 1962, hoping that Grand Valley could graduate its first class as an accredited college. He hired a consultant, who visited campus in November 1963, just a month after classes began. The consultant helped the college prepare for an official visit by an NCA team in November 1964 that would determine if Grand Valley could be accepted as a Candidate for Accreditation. Their report was very favorable, although it did contain the line quoted in the Press: "The weakest element in the present GV picture is the quality of the student body. Relatively, the students fall far short of the quality of the faculty."

Although the accrediting agency was critical of Grand Valley's early students, there were many who thought the school was attracting an impressive group of young people who brought an interesting perspective to the new college. John Tevebaugh, professor of history from 1962-1988, remembered in a 50th Anniversary Video History interview that, "It was impressive how much study they would undertake," describing them as among the first in their families who went to college, and teaching them as "a refreshing experience."

Zumberge Library under construction, 1968.

The college was accepted as a candidate in March 1965, and the administration were hopeful they might achieve their goal. But the NCA decided to deny the request for exemption from its requirement that one class graduate before considering the application for membership. "That ended the battle for early accreditation for GVSC," wrote Zumberge in his 1969 report.

Anticipating that possibility, however, the college had begun negotiations with the Michigan Commission on College Accreditation in December, 1964. "After much foot-dragging by that group and considerable prodding on our part," wrote Zumberge, an examining committee visited the campus in February 1966, and three-year accreditation was granted. Lack of NCA accreditation also prevented Grand Valley from providing teacher certification. An arrangement with Michigan State University made it possible for Grand Valley education students to enroll during their senior year so MSU could act as the legally authorized certifying authority, an arrangement which continued until Grand Valley was accredited in 1968.

II. Tweaking the Vision

In the fall of 1965, Academic Dean George Potter announced to the first meeting of the Faculty Assembly that changes must be made to the idealistic liberal arts curriculum in order to attract more students. A group calling itself the Committee on New Academic Programs was formed. In a 2009 interview for the 50th Anniversary Video History Project, Glenn Niemeyer, who retired from Grand Valley in 2001 as its first Provost, but in the mid-1960s was a professor of history, remembered informing President Zumberge about the group and their recommendations to expand the curriculum. "I went to talk to Jim about it," he recounted. "He and I had a very good conversation about it. He seemed openly receptive to the idea of expanding the curriculum and adding professional programs to it. Shortly thereafter, Jim left."

In the fall of 1966, the Faculty Assembly voted to recommend granting the Bachelor of Science degree at Grand Valley. By January 1967, the degree was in place. The doors were opened, wrote Zumberge, for a broader range of majors, including business administration, physical education, group majors in social studies and general science, medical technology (in cooperation with area hospitals), and engineering (a collaboration with the University of Michigan). "The college was able, by its own internal action, to initiate change when change was needed in order to survive," wrote Zumberge in his 1969 report.

The changes had an effect on enrollment, in both quantity and quality. By the fall of 1967, one-third of the entering freshmen had high school grade point averages of "B" or better, compared to one-tenth of entering students in the fall of 1963. Geographic distribution also changed. 75% of the student body still hailed from the eight-county area, but Grand Valley was now attracting students from throughout the state, plus 3% from other states and Puerto Rico. Only 65% lived at home compared to 90% of the pioneer student body.

On June 18, 1967, Grand Valley State College held its long-dreamed-of first commencement. In a tent on the Allendale campus, 138 seniors, including 86 members of the pioneer class that started in 1963, received their diplomas from Michigan's newest college. Harlan Hatcher, president of the University of Michigan, gave the commencement address. Coincidentally, for this 50th Anniversary History of Grand Valley, he spoke at length about the year 2010. "You will retire around 2010," he told the young graduates. "No one could possibly chart your course through these years, or risk foretelling what the world will be like ... One thing is reasonably certain: your grandchildren will think you aged and old-fashioned, out of tune with youth and the modern world of the 21st century. And they will try to redeem and overcome all the grave mistakes you will make in bringing up and educating your children, running the government, devising an intelligent foreign policy, and fighting unnecessary wars." He ended, "Best wishes between now and 2010."

President Zumberge speaking at the first GVSC Commencement Ceremony, 1967.

III. A Second Society

While most of the faculty at Grand Valley were happy with the academic changes that brought more students to the Allendale campus, there were some who were disappointed by the diminishment of the school's traditional liberal arts focus. George Potter, now Vice President of the college, had been pursuing his earliest suggestions for decentralized collegiate societies, based on European models, specifically his experiences at Oxford University in England. In 1966 he appointed a Committee on Collegiate Societies, from which developed the Second Collegiate Society Study Group. The report of the group in 1967 proposed that a new satellite collegiate society would "recover the early commitment of Grand Valley State College to the tradition of liberal studies, but will also restore as the central feature of its program the pedagogical ideal implicit in the tutorial." They proposed a curriculum that focused on a "continuing community meeting," what came to be know as the "common program." The new school also would offer opportunity for independent study such as examination courses, seminars, off-campus projects, and special studies. Grades would be either satisfactory or unsatisfactory, with narrative evaluations by professors appearing on student transcripts.

There was a movement occurring nationwide as part of the social, political and demographic changes that were deeply affecting higher education in the 1960s. Many experimental or innovative new colleges, or divisions within established institutions, were attempting to redefine the experience of college students. Words such as experiential, interdisciplinary, student-designed curriculum, and participatory governance have been used to describe these programs, which appeared from Maine to California, from Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington to the New College in Florida. In Michigan, Wayne State, Michigan State and the University of Michigan had opened new units to attract students interested in innovative educational ideas.

Poet Robert Bly instructing Thomas Jefferson College fine arts class.

In the fall of 1968, the School of General Studies (SGS, later renamed Thomas Jefferson College) opened at Grand Valley State College with 80 students and three full-time faculty. Other professors in the larger division at Grand Valley now known as the College of Arts and Sciences had dual appointments in both schools. The curriculum was not exactly what Vice President Potter had envisioned for his new academic society. In an article written by Grand Valley Professor Lynn Mapes in 1995 for a History Department project on the early history of the college, he describes Potter as unhappy with the substitution of "concentration" for the traditional major, and with "no grades, no courses, no degrees." Mapes, who joined the Grand Valley faculty in 1968, quotes Potter as huffing, "The Board of Control do not view decentralization primarily as an opportunity to play around with wild notions of what a liberal education can be."

In the first brochure developed to describe Grand Valley in 1962, the prospective student body was characterized as "able surprises -- students with a talent for creativity who give promise of rising to the challenge of an imaginative college program." It was apparent from the first days of SGS that the progressive new program would be attracting exactly those surprising students. Dan Clock, formerly in the math department at Grand Valley and now the new SGS chair, told the Valley View student newspaper, "There was a feeling of euphoria among the SGS faculty and students, and excitement in starting from scratch reminiscent of the esprit de corps when the Pioneer Class arrived." In an interview with the Detroit Free Press at the end of SGS's first academic year, he quoted Kierkegaard in describing the program: "A teacher cannot teach; he only makes an atmosphere in which a learner learns."

The academic euphoria shared by the SGS pioneers would be somewhat short-lived. But first, the college as a whole would have to rise to its next challenge: finding a new president.

IV. The Arrival of Arend Lubbers

While college faculty were hard at work determining the academic direction of Grand Valley, President James Zumberge and the administration were still deep in the accreditation process necessary for the success of any curriculum. Just before the college's first commencement ceremony, Zumberge flew to Chicago with two copies of the required institutional self-study in hand. In August NCA notified the college that the study was accepted and scheduled an accreditation exam. A team arrived in January 1968. Their report, though mostly favorable, questioned the launch of the Second Society. Zumberge and Potter were off to Chicago again, "with a suitcase full of data and reports," wrote Zumberge in his 1969 report. "By the time we were ready to appear before the (Committee) at 8:30 a.m. on March 25, 1968, I felt more like an attorney than a college president," he wrote. The committee meeting lasted less than a half hour, and all the prepared data and reports were accepted without questions. "The final decision to grant accreditation for a ten-year period … was delivered to me Wednesday (March 27, 1968) morning and was almost anticlimactic."

NCA accreditation certified that Grand Valley State College offered an acceptable academic program and had the necessary resources to accomplish its stated objectives. While that may seem like a bland statement, it was the culmination of a decade of work by community, faculty, administration and even students to bring the new college into existence and raise it to its proper place among its academic peers. Was it a coincidence that just the next month, James Zumberge announced that he would leave the presidency of Grand Valley to return to teaching as the director of the school of earth sciences at the University of Arizona? While many people who were at Grand Valley at the time said that the general feeling was that President Zumberge was frustrated by the tribulations of administration and wanted to return to a more academic life, he later served as president of Southern Methodist University, and retired as president of the University of Southern California in 1991. He died shortly afterward.

Grand Valley's second president, Arend D. "Don" Lubbers.

The Board of Trustees appointed a search committee including college faculty, alumni, students, and members of the committee who had worked to establish Grand Valley. Bill Seidman remembered the next events in his 50th Anniversary Video History Project interview. "We heard about this youngest college president in the United States and he was out there in the middle of nowhere in Iowa," he recounted. "I remember I flew out there in our plane to take a look at a guy named Arend Lubbers, who happened to be the son of the president of Hope College. And Hope College was not one of the institutions that was enthusiastic at that time about Grand Valley getting started. I spent about a half a day with Don Lubbers and I said, 'I think this is the man we want.' So we went forward from there, fortunately we got him. Today’s world, I doubt if ever we could do that. He didn’t have a Ph.D. at the time, he was going through a divorce, a lot of things that in today’s so-called “open society” or whatever you want to call it, would have made it difficult. Fortunately he came, he met with the Board, he introduced us to his new bride-to-be, Nancy, who was terrific, and he was unanimously elected by the Board to be the president. I’ve often said I’ve worked hard for Grand Valley, but the best thing I ever did was recruit Don Lubbers to be the president."

Arend Donselaar Lubbers, who urged everyone to call him Don, grew up on college campuses. His father was president of Hope College from 1945 to 1963, and was professor and president of other colleges before that. Don graduated from Hope and earned his MA in History from Rutgers University in 1956. He taught at Wittenberg College in Ohio before returning to Rutgers in 1958 to pursue a doctorate. In 1960 he was appointed president of Central College in Pella, Iowa at the age of 29, becoming the youngest college president in the nation. Two years later, the young academic attracted national attention when Life magazine included him in its 1962 feature "Red-Hot Hundred," profiling 100 outstanding American leaders under 40.

Lubbers was still among the youngest college presidents in the nation when he accepted Grand Valley's offer in December 1968. He would need all the youth and vigor he could muster as he stepped into a swirl of contention and controversy that mirrored the mood of the nation as the decade drew to a close.

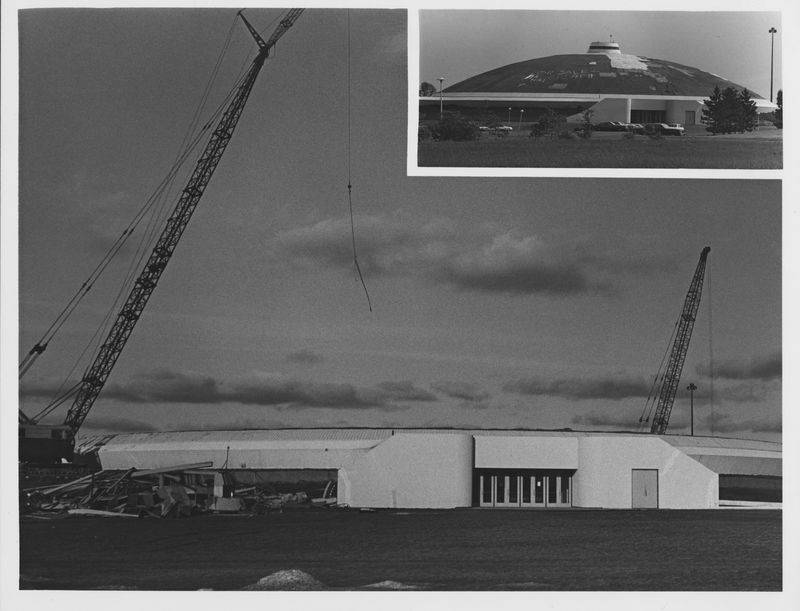

At the end of February 1968, the domed roof of the innovatively designed new Fieldhouse at Grand Valley had given way under construction, and a worker had been critically injured. Some with memories of Grand Valley's early years cite this as something of an omen, ushering in a period of dissension, strife and public criticism that would threaten the very existence of the fledgling college.

Before Don Lubbers' term of office officially began in January of 1969, calls from Board members alerted him to problems surrounding the college newspaper, the Lanthorn. Near the end of November 1968, deputies from the Ottawa County Sheriff's Department had entered the campus office of the newspaper and confiscated copies of the latest issue. On December 3, the Ottawa County Circuit Court issued a complaint charging its editor with publishing obscenity and an injunction stopping its publication. The offense was characterized as the use of supposedly obscene words. But it was felt by many that the real issue at stake was the newspaper's coverage of political matters that were tearing the country apart in the late 1960s: the war in Vietnam, the drug culture, criticism of military and police tactics, student rights and civil rights. The Lanthorn under the leadership of editor Jim Wasserman had improved in journalistic style and relevant academic, artistic and political content over its predecessor student newspapers, but no one could dispute that it had become radically left wing, at odds with the conservative values of Ottawa County.

Although the editor was fired and publication of the newspaper suspended, Grand Valley brought a lawsuit questioning the authority of the prosecuting attorney and the sheriff in issuing an injunction halting publication. In August 1969, the Attorney General of Michigan ruled that the Ottawa County authorities did not have legal authority in closing the newspaper. The editor stood trial in the district court and was found guilty. There was a great deal of debate among faculty, student, and alumni organizations about whether to ask the college to aid in the editor's defense; in the end the Board of Control decided it would not. According to a Grand Rapids Press article in October, 1969, "1968-69 was the year of the four-letter word on many campuses," citing clashes between administration and student journalists at Purdue and the University of Minnesota. "Only at GVSC, however," the article reported, "was the student editor actually arrested."

Students around the U.S. and internationally were mobilizing around issues of freedom, war, equal rights, and the environment, and even at remote Grand Valley, the wave of unrest could be felt. In 1967 the first political demonstration at Grand Valley was held by a group of anti-war students and faculty members who picketed U.S. Senator Phil Hart on a visit to campus, although his views about the war ended up being more in line with theirs. By the fall of 1969, when the campus was celebrating the inauguration of Don Lubbers, marches, demonstrations and moratoriums were an almost weekly function.

Grand Valley students were doing more than marching, however. Awakening activism spurred some to participate in community outreach programs established by the college, such as Project Make-It to help high school dropouts enter college, the Urban Studies Institute focusing on problems and needs in downtown Grand Rapids, and a new Latin American Studies program. Grand Valley also began to offer its first study abroad programs, offering students opportunities at the University of Lancaster in England beginning in 1969, a program in Merida, Mexico, and one in Tours, France.

Group of students protesting the Vietnam War., ca. 1968

The new President was sympathetic to the spirit of the students (not being all that much older than they were). He participated in National Moratorium Day activities, lighting a gas flame in Mackinac/Manitou Plaza intended to burn until the end of fighting in Vietnam. He encouraged debates, teach-ins, guerilla theatre and many opportunities for discussion of pressing issues, brought home to the campus by the deaths in Vietnam of two former students.

Lubbers and the Board of Control also realized, however, that the growing institution would continue to face the problems of any large group of people living and working together. In February of 1969, William A. Johnson was appointed the first Campus Police Chief at Grand Valley, responsible for setting up a college security force. Johnson joined the Grand Rapids Police force in 1940 and was Superintendent for over 11 years. In his initial statement to the Press, he referenced the civil unrest that had been sweeping the nation over the past few years, specifically riots in Detroit and Grand Rapids. "The philosophy of non-violence and persuasion that we advocated during Grand Rapids' summer disturbances," he stated, "is particularly applicable to work with students."

In his inaugural address on October 12, 1969, Don Lubbers faced the issues squarely. "Despair has grown in the midst of the affluence that characterizes this nation," he told the assembly in the newly dedicated Fieldhouse. "Our educational institutions were for generations the focal point of the nation's social and industrial optimism … they have not escaped from the spreading despair. …The conflict inherent in the outside society has incited simultaneously a vicious indictment of the entire American educational system. The same reason that young people see for despair in the world outside the university they see writ just as large inside."

Lubbers chose to frame the problem in terms of academic relevance. "I am not here to take sides," he declared. "I see the office of president of a college as a place where the inevitable human conflicts are arbitrated and issues settled. Let me bring some issues to bear to illustrate what I mean. I have been told by some that this college must choose between liberal arts and specialized or technical training. How many colleges have been fooled or pushed into a bifurcation of this issue? Is this college to take up the sword for liberal arts while ignoring a society that demands from its schools the trained personnel to keep our economy alive? Or are we to man the barricades for technical training at the expense of educating the critical and historically conscious minds that a healthy democracy demands? I will endorse neither such approach. This college was built on a solid liberal arts basis and there it will stay."

Grand Valley and President Lubbers set out to accomplish this broad goal by initiating a program of academic expansion and division that would result in the school's famous "cluster college" era, again drawing national attention for innovative new approaches to education while creating challenges of marketing these approaches to students and the surrounding community. It would take another decade of hard work to bring the goals put forth by the new President into sharp focus.

1970-1980

I. The Cluster Concept

As the 1960s drew to a close, it seemed as if the new ideas about education percolating at Grand Valley State College were beginning to reap rewards. Enrollment in 1969 hit an all-time high, and in fall 1970 passed the 3000 mark. Another living center, named for founding Board of Control member Grace O. Kistler, was constructed in the curving dorm complex along the north campus ravines in 1971, along with a Fine Arts Center on the south campus.

The new president of the college, Don Lubbers, moved swiftly to build on the cluster college concept that, although foreshadowed in the earliest talks about curriculum, had begun just before his arrival with the establishment of a "second society" in 1968. The School of General Studies (described in the previous section of this history), was renamed Thomas Jefferson College in the fall of 1969.

The idea of offering experimental education was not unique to Grand Valley. Lubbers, in a 2008 interview for the 50th Anniversary Video History Project, remembered that it reflected, "a society that was beginning to look for experiments in higher education - to change it, to improve it," or, he continued, "at least in that part of society that was young and college bound, there were a number of them who wanted alternative ideas in higher education."

While renewed interest in experimental education did not originate at Grand Valley, the college's 10-year process of developing separate academic units organized around ideas rather than residential groups was particularly inspired. Over the next decade, Grand Valley would become a proving ground for innovations in education that attracted faculty and students from across the country, and, while often problematic and controversial, set a stage for discussions of teaching and learning that still resonate at the college today, and, some believe, shaped Grand Valley as exceptional among similar public institutions nationwide.

II. William James College

As the School of General Studies (TJC) was emerging, yet another planning task force had been meeting, interested in new ideas about education but taking as a model the work of 19th century American philosopher William James.

Conceived as an interdisciplinary, non-departmentalized college with concentration programs instead of majors and a common core of study (similar to Thomas Jefferson), the new unit differed from the "second society" in a very specific delineation of goals in the original blueprint for the college: "William James College will be future-oriented, since its programs will correlate with society's projected needs; it will be career-oriented, since its concentrations will lead to clearly defined professional opportunities, as well as to advanced studies; it will be person-oriented, in that its programs will stress intellectual and personal maturation within a community of learners."

Student working on the William James College mural.

In the fall of 1971, 160 students and six faculty met in their new headquarters, Lake Superior Hall, for the first of what would become a hallmark of the school, the Synoptic Lectures. Designed as a counterpart to what many colleges offered as foundation or distribution courses, the Synoptic (literally "seeing together") Program that included the lecture series was planned to "acquaint students with a variety of intellectual fields," and provide an opportunity for "developing their own broad and comprehensive view of human experience." The initial series, titled "William James - Our Contemporary," featured scholars from the University of California Berkeley, Harvard, the University of Chicago, Yale and others, including Martin Marty, Jerome Kagan, and David Elkind.

In an article for the Grand Valley Review in Fall 1995, Richard Paschke, one of the first six WJC faculty, wrote that the demands of curriculum development and heavy teaching commitment "wreaked havoc on the personal lives and health of many WJC faculty and staff members in the early years. Yet," he continued, "so brightly burned the flame of William James' original vision that the pace of development held steady and even quickened in the second year of the college's existence: hired then were twelve new faculty members, including six women, one of whom, Adrian Tinsley, became its first full-time dean."

Over the next decade, the William James College philosophy of pragmatic education would draw national attention, including a prestigious 1977 grant from the U.S. Office of Education for a demonstration project in providing a career education at a liberal arts college. Students in several area concentrations would make an impact on the West Michigan community, including activities in urban and environmental studies, social relations, and information technology. But by the fall of 1974, according to a college self-study for NCA accreditation review, 34% of WJC students were concentrating in the Arts & Media program, a foundation for the strength of Grand Valley's current Film & Video major in the School of Communications.

Barbara Roos, a member of the Arts & Media faculty who joined the School of Communications when WJC was closed, has made a one-hour documentary titled "William James College: An Unfinished Conversation."

III. College IV (Kirkhof College)