This is the story of an immigrant who settled in West

Michigan, who contended with rapid and immense societal change, who

withstood the isolation of a pandemic and who, while influenced by

world travels, celebrated the beauty in his local surroundings.

It is a story told through a paintbrush as the 20th century dawned,

by a German-born artist who always stayed true to himself by painting

the world his way, in the way he saw it.

When Mathias Alten saw modernization, he favored depicting nostalgic

rural scenes. When he experienced the isolation of the 1918 pandemic,

he looked within, resulting in a notable number of self-portraits

during that era. When he traveled domestically and internationally, he

often painted with a burst of inspired creativity.

But no matter the inspiration from international travels, which

included many major artistic and cultural centers, he always came back

to Michigan.

“Alten painted the landscape of Michigan throughout his entire career

from different perspectives,” said Nathan Kemler, director of Grand

Valley’s galleries and collections. “He painted the lakeshore, the

cities and the rural areas.”

Joel Zwart, curator of exhibitions for the Art Gallery, moves artwork

for the exhibition.

Kemler said these environmental landscapes were what initially spoke

to George Gordon, who along with his wife, Barbara, donated 35

paintings in 1998 to initiate Grand Valley’s collection of the

impressionist artist referred to as the Dean of Michigan painters.

The momentum that ensued after that initial donation, and with

continued support, has led to Grand Valley holding not only the

world’s largest public collection of the artist’s work but also the

entire artist Catalogue Raisonné and published scholarship.

“All of this is only possible because of the Gordons’ contributions

and their passion not only for Mathias Alten but also art in general,”

Kemler said. “The Gordons could have done several different things

with that collection. They shared our vision that works need to be

seen, they need to be shared and they need to be out in front as much

as possible, not in storage.”

That is why it is appropriate that on the occasion of the 150th

anniversary of Alten’s birth in 1871, the Art Gallery is sharing his

enduring legacy throughout the state in a traveling exhibition.

Preparing the pieces for the traveling exhibition involved meticulous work.

Telling Alten’s Story Statewide

The first stop for the exhibition, “Mathias J. Alten: An American

Artist at the Turn of the Century,” was the Dennos Museum Center in

Traverse City. Other scheduled venues are the Daughtrey Gallery at

Hillsdale College, the Michigan Historical Museum in Lansing and the

Muskegon Museum of Art, said Joel Zwart, curator of exhibitions for

the Art Gallery, who added officials are working through hosting dates

due to the uncertainty from COVID-19.

The exhibition includes more than 40 works drawn from the Art Gallery

collection, historical photos and personal artifacts such as brushes

to fully tell the story of Alten’s life, Zwart said.

“In some ways, we see this exhibition as a gift to the state of

Michigan,” Zwart said.

Said Kemler: “Narratives of empathy, peace, love, social justice,

equity — all core elements to what it means to be human — are told

through art. I believe the stories art tells belong to everybody, and

we want to take these stories into our communities and across our state.”

One artist’s take on change

Alten’s story is in many ways a timeless one of someone trying to

make sense of change, Kemler said. In Alten’s time, he witnessed rapid

advances in transportation, industry, agricultural machinery and more.

“While he was living with it in his every day, he decided to paint

what was happening before these great changes,” Kemler said. “Everyone

embraces change differently.”

Alten would use artistic license to hide modernization, Kemler said.

If Alten was painting a landscape dominated by a smokestack, he would

omit it. Kemler also noted that of the approximately 3,000 works Alten

created, only one contained the image of a car.

Alten showed a particular affinity for painting agricultural scenes

showing oxen, horses or more traditional equipment, Kemler said. Alten

would even depict these operations from what he saw while traveling

internationally to such places as the Netherlands or Spain, but many

of the prevalent scenes were from Michigan.

In fact, Alten would use modern transportation such as the electric

interurban to travel to Ottawa County farmlands to paint these favored

scenarios, said Matthew Daley, associate professor of history and an

expert on West Michigan history. Many farmers in that area had small

operations and it made sense to continue with traditional agricultural

methods such as animal power.

Daley incorporates Alten into his coursework on local history as well

as urban and industrial history. While some art of that era glorified

industry, Daley said Alten’s general shunning of modernization

provides an important counterpoint for students as they study

industrialization and how it affected Grand Rapids.

“I want students to think of other depictions of Grand Rapids, the

industrial life, and the different representations of West Michigan

especially during his lifetime and that transformation,” Daley said.

“Alten did a number of works depicting Grand Rapids with his style,

and he presents a particular image of the city, always with a focus on

the river.”

Daley has taken his students to the George and Barbara Gordon Gallery

on the Pew Grand Rapids Campus and has enjoyed watching them reflect

on what they saw in paintings when they then go out into the city.

He said a number of students find they connect with Alten’s more

straightforward artistic style. Kemler noted Alten’s work is more

subtle as opposed to hitting viewers with emotion, inviting them to

slow down and reflect.

The gallery named for George and Barbara Gordon, whose initial

donation set Grand Valley on course to hold the world’s largest public

collection of Mathias Alten paintings.

Lasting Impact

Since that initial donation more than 20 years ago, the collection

has grown well beyond initial expectations, Kemler said. It includes

120 works in two dedicated galleries as well as three different

dedicated endowment funds set up around Alten.

The gallery is generally open for free every Friday and Saturday,

which matches Grand Valley’s mission of offering a borderless,

barrier-free gallery. Kemler is envisioning ways to continue to tell

Alten’s story and highlight the nuances, helping us see ourselves.

The impact from the faith that the Gordons put in Grand Valley to be

stewards of these works, part of the third-largest art collection in

the state, was both immediate and long-lasting, Kemler said.

“The magnitude of the Alten collection is that it is a premier

collection that initially put Grand Valley on the art map,” Kemler

said. “Alten is one of the most important painters in the history of

Michigan and is a known painter across the country, and we have been

able to raise awareness about him through Grand Valley, giving him

higher visibility.”

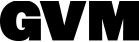

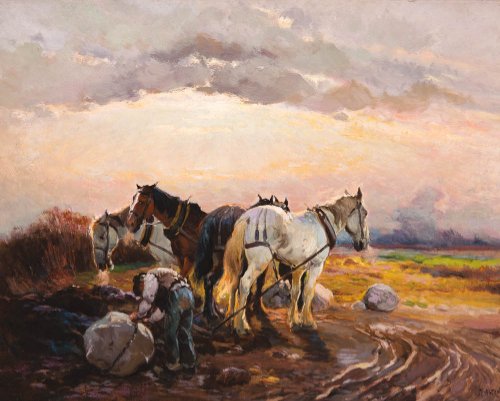

Mathias J. Alten, Hauling the Boulder, 1910, oil on canvas.

GVSU Art Gallery, Gift of George H. and Barbara Gordon (2016.65.1)

Over his career, Alten returned to paint scenes that combined manual

labor and the rural Michigan landscape. This piece illustrates Alten’s

commitment to that subject matter. In it, we see a farmer bending down

to connect a boulder to his team of horses, whose breath is visible in

the cold air. Above them, the sun begins to break through dark clouds,

illuminating and warming this agrarian landscape.

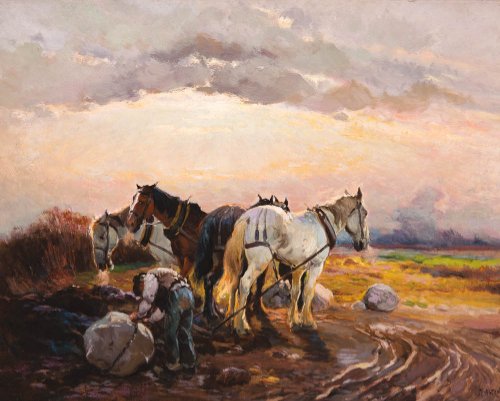

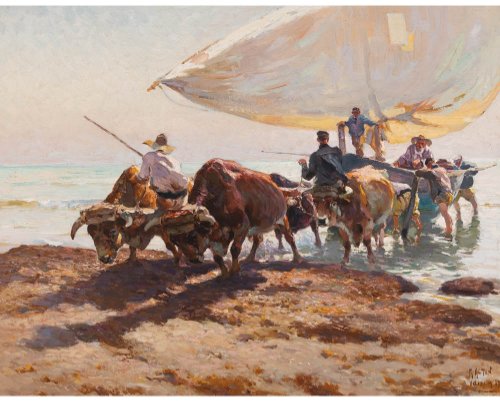

Mathias J. Alten, Oxen, Boat and Fishermen, Valencia, 1912,

oil on canvas. GVSU Art Gallery, Gift of George H. and Barbara

Gordon (2018.66.1)

Alten’s visits to Spain had a profound effect on his work, and

contributed to the lightening of his palette. As in his experience in

the Netherlands and other locations, Alten sought out environments

with traditional laborers and nostalgic settings. Here we see

traditional Spanish sardine fishermen using oxen to pull their boats

onshore near Cabañal.

Mathias J. Alten, Self Portrait, Myself at 66, 1937, oil on

canvas. GVSU Art Gallery, Gift of George H. and Barbara Gordon (2009.90.1)

This piece from 1937 is the last known self-portrait he completed, as

he passed away the following year from a heart attack.

Self-portraiture was something Alten returned to on a number of

occasions in his lifetime, including the period during WWI and the

1918 flu pandemic when he painted quite a few from the confines of his

studio (albeit more formal than this one).

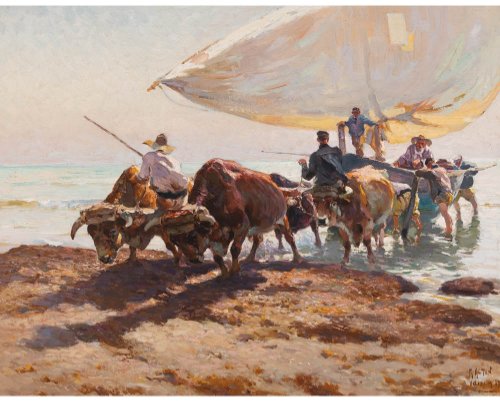

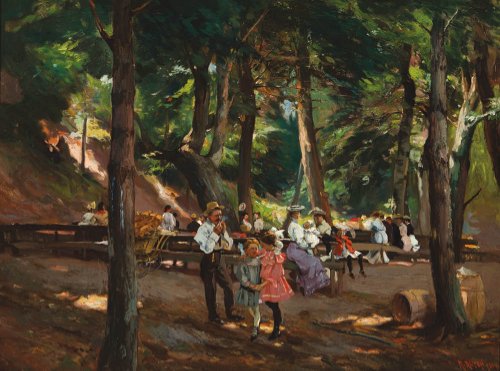

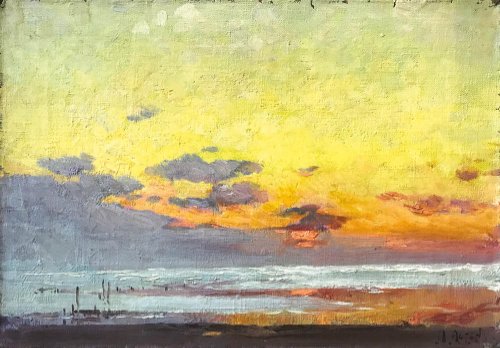

Mathias J. Alten, Picnic at Macatawa, 1904, oil on canvas.

GVSU Art Gallery, Gift of George H. and Barbara Gordon (1998.580.1)

This is a quintessential West Michigan scene. Alten painted many

landscapes around the interior of the state of Michigan during his

lifetime, and also spent time along the lakeshore. Here we see the sun

slowly sinking amidst clouds over Lake Michigan, casting pink, orange,

yellow and purple throughout the composition.

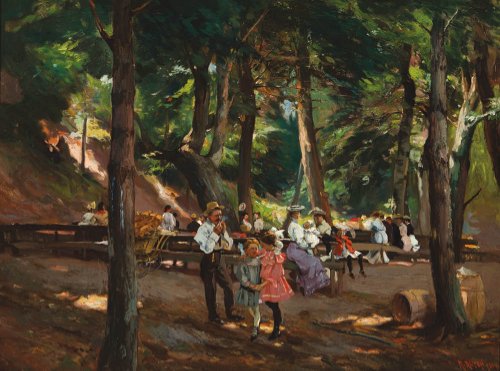

Mathias J. Alten, Picnic at Macatawa, 1904, oil on canvas.

GVSU Art Gallery, Gift of George H. and Barbara Gordon (1998.580.1)

Finally, this earlier work by Alten is an autobiographical account of

his family enjoying a picnic in the dunes near Holland, Michigan. By

the start of the 20th century, recreational activities became

increasingly accessible to the middle and working classes. Residents

of Grand Rapids, such as the Altens, would take the electric

interurban to the lakeshore to enjoy time away from work and the city.

This wonderfully intimate scene also illustrates the influence of

Impressionism on Alten. Using visible brush strokes, Alten emphasizes

the changing qualities of light as it is filtered through the trees.