Innovation Corner

Permanent link for Improvise, Adapt, Overcome on April 12, 2024

Entrepreneurs can glean invaluable insights from the Marine Corps Fighting Doctrine's mantra: "Improvise, Adapt, Overcome." In today's dynamic business environment, adaptability is not just beneficial—it's essential. Successful ventures pivot swiftly and innovate to navigate unforeseen challenges.

Improvise

Entrepreneurs often encounter unexpected obstacles that disrupt their plans. As the military adage goes, "No plan survives first contact with the enemy," entrepreneurs must be prepared to deviate from their original strategies. Similar to Marines on the battlefield, they must think creatively, leveraging available resources in unconventional ways to overcome adversity.

Adapt

Adaptability lies at the heart of both military strategy and entrepreneurship. "Slow is smooth, smooth is fast," emphasizing the importance of methodical action even under pressure. In entrepreneurship, staying agile and responsive to changing market dynamics is crucial. Being able to adjust strategies swiftly to new trends and competitive landscapes is key to success.

Overcome

Resilience is paramount in the face of adversity. "Embrace the suck," urging individuals to endure difficult situations without complaint. Entrepreneurs must confront challenges head-on, prioritizing both objectives and the well-being of individuals, as emphasized in "Mission first, people always." By navigating setbacks with determination and grit, entrepreneurs can emerge stronger and more successful.

Conclusion

The Marine Corps mantra illuminates the path to entrepreneurial success. By embracing flexibility, adaptability, and resilience, entrepreneurs can thrive amidst challenges. Channeling the spirit of improvisation, adaptation, and overcoming fosters excellence in entrepreneurship, ensuring ventures not only survive but flourish in the ever-evolving business landscape.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

management

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Improvise, Adapt, Overcome on April 12, 2024.

Permanent link for Mastering the Fail-Fast Approach: A Blueprint for Entrepreneurial Success on April 5, 2024

Throughout my career, I've focused on developing cutting-edge technologies and products. One of the most influential figures I've worked with, a brilliant scientist, introduced me to the concept of "fail fast."

Previously, my approach revolved around testing various inventive ideas and assessing their viability. As a team, we aimed to replicate successful outcomes and iterate on new concepts.

While we experienced some successes, we also encountered numerous failures, some of which were avoidable and overshadowed our achievements. Failure can come with significant costs.

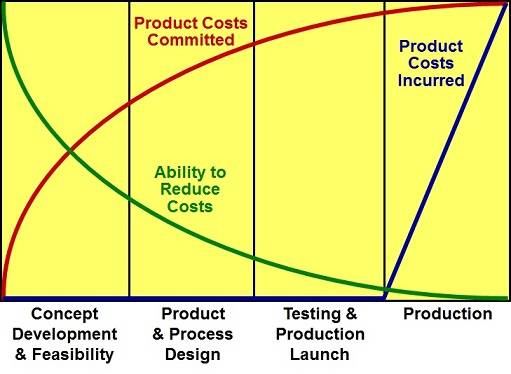

As we progress towards market launch, flexibility decreases, and changes become more expensive. Simultaneously, development expenses escalate, making it crucial to identify and address potential flaws early on to minimize costs.

The fail-fast mindset acknowledges that no idea is perfect and seeks to identify weaknesses swiftly and efficiently. Rather than focusing solely on success, the emphasis is on identifying and mitigating failure points.

To implement this approach, it's essential to define clear hypotheses and develop a comprehensive test plan. For example, testing different website designs through A/B testing to determine their impact on conversion rates.

By embracing the fail-fast approach, entrepreneurs can quickly learn from mistakes and make necessary improvements. Failure becomes an opportunity for growth rather than a setback.

When developing new products or services, the costs spent on development increases, while the flexibility in making changes to the design of the product or service decreases. Image from NPD Solutions.

Categories:

innovation

management

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Mastering the Fail-Fast Approach: A Blueprint for Entrepreneurial Success on April 5, 2024.

Permanent link for Unveiling the Synergy Between Business Model Canvas and the 4Ps in Product Innovation on March 29, 2024

Two common tools for strategizing and executing business plans are the Business Model Canvas (BMC) and the Marketing Mix, famously known as the 4Ps (Product, Price, Place, and Promotion). While these frameworks are often discussed independently, their overlap can unlock a powerful synergy, enhancing the depth and effectiveness of your business strategy.

The Business Model Canvas, pioneered by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur, offers a holistic view of a business model by breaking it down into nine key building blocks: Customer Segments, Value Proposition, Channels, Customer Relationships, Revenue Streams, Key Resources, Key Activities, Key Partnerships, and Cost Structure. This framework serves as a blueprint for understanding how a company intends to create, deliver, and capture value.

The 4Ps framework, introduced by E. Jerome McCarthy, focuses on the essential elements of marketing strategy: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. It delves into the core components of a marketing plan, guiding businesses in crafting strategies to effectively market their products or services.

While the BMC and the 4Ps might seem distinct at first glance, they converge in several critical areas, particularly concerning product strategy:

-

Product (Part of 4Ps) and Value Proposition (Part of BMC): The product is central to both frameworks. In the 4Ps, product strategy involves decisions regarding product features, branding, and differentiation. Similarly, the Value Proposition block in the BMC encapsulates how a product or service solves a customer's problem or fulfills a need in a unique way. Aligning these two concepts ensures that the product's attributes resonate with the target market's preferences and demands.

-

Price (Part of 4Ps) and Revenue Streams (Part of BMC): Pricing decisions directly impact revenue generation, making the alignment between Price and Revenue Streams crucial. The Price component of the 4Ps framework guides entrepreneurs in setting optimal pricing strategies, considering factors such as costs, competition, and perceived value. Correspondingly, the Revenue Streams block in the BMC outlines how the company monetizes its value proposition. By harmonizing pricing strategies with revenue models, businesses can ensure profitability while delivering value to customers.

-

Place (Part of 4Ps) and Channels (Part of BMC): Place, in the context of the 4Ps, refers to the distribution channels through which products reach consumers. Channels, a key element of the BMC, delineate how a company delivers its value proposition to customers. Integrating these concepts involves selecting the most suitable distribution channels to reach target customers efficiently. Whether through direct sales, online platforms, or intermediaries, aligning Place with Channels optimizes the product's accessibility and enhances the overall customer experience.

-

Promotion (Part of 4Ps) and Customer Relationships (Part of BMC): Promotion encompasses marketing communications activities aimed at raising awareness and driving sales. On the BMC, Customer Relationships elucidate how a company interacts with its customers to cultivate loyalty and satisfaction. By aligning promotional efforts with the desired type of customer relationships (e.g., personal assistance, self-service), businesses can tailor their marketing campaigns to effectively engage with their target audience, fostering long-term relationships and brand advocacy.

In essence, while the Business Model Canvas provides a comprehensive framework for mapping out the various components of a business model, the 4Ps framework offers a focused lens on marketing strategy. By recognizing their intersections and aligning the relevant elements, entrepreneurs can craft cohesive and robust business strategies that resonate with customers, drive value creation, and fuel sustainable growth. Embracing this synergy empowers innovators to navigate the complexities of product innovation and entrepreneurship with clarity and purpose.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

marketing

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Unveiling the Synergy Between Business Model Canvas and the 4Ps in Product Innovation on March 29, 2024.

Permanent link for How to Price Your Product: Understanding the Difference Between Price and Cost on March 8, 2024

Understanding Product Pricing: Navigating the Price vs. Cost Conundrum

As entrepreneurs and intrepreneurs venture into the world of product development, they inevitably encounter the question: "How much does it cost?" This seemingly simple query actually warrants a deeper understanding, as it involves distinguishing between price—what the customer pays—and cost—what it takes for you to deliver the product to the customer's hands. Moreover, it's essential to differentiate between current costs and those at scale.

1. Addressing Customer Inquiries: The Price Perspective

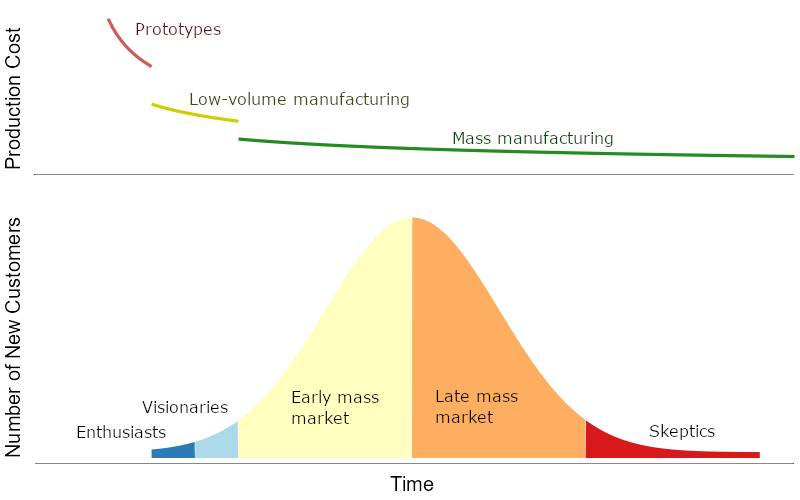

When engaging with potential customers, particularly those eager to make a purchase, their primary concern revolves around the immediate price. For them, the question translates to, "What's the price, right now?" It's imperative to have a response ready to validate the market and encourage sales. Initially, pricing should focus on market testing rather than operational efficiency. Aim for a premium price point to gauge market receptivity, keeping in mind that early pricing need not correlate with actual costs.

2. Meeting Investor and Stakeholder Expectations: The Cost at Volume

Conversations with investors or internal stakeholders typically revolve around the cost at volume. While estimating costs at scale may seem daunting, it's feasible with a strategic approach. Rather than pinpointing exact costs for every component, identify the key cost drivers and approximate their expenses at the highest feasible volume. For instance, if you're envisioning mass production of a smartphone, aim for a volume estimate that aligns with market demand while remaining realistic.

3. Illustrating Cost Dynamics: A Practical Example

Consider the scenario of manufacturing smartphones in China and shipping them to the U.S. west coast. Initially, shipping costs per phone may be significant. However, as volumes increase, economies of scale come into play, driving down the per-unit shipping cost substantially. Such insights allow you to provide stakeholders with informed estimates, demonstrating the potential cost reductions at scale.

4. Embracing the Cost-Volume Relationship

The relationship between cost and volume applies universally across products and services. As your operations scale, variable costs become increasingly dominant, leading to lower per-unit expenses. This dynamic underscores the importance of targeting high-value customer segments early on, prioritizing premium pricing over cost-conscious mass markets.

5. Navigating Market Opportunities

While high-value customer segments are often the initial focus for startups, exceptions exist. Certain market opportunities may lie in cost-conscious segments, where underserved customers seek affordable alternatives. By offering lower-margin substitutes with strategic feature adjustments, startups can carve out a niche and gain market share.

In conclusion, mastering the interplay between price and cost is essential for entrepreneurial success. By understanding customer expectations, investor perspectives, and cost dynamics, startups can navigate pricing challenges effectively, paving the way for sustainable growth and profitability.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

management

marketing

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for How to Price Your Product: Understanding the Difference Between Price and Cost on March 8, 2024.

Permanent link for Innovation on February 9, 2024

In today's fast-paced business landscape, the key to success often lies in the ability to innovate quickly and bring products to market faster than the competition. For businesses striving for relevance and growth, an efficient innovation process is not just a luxury; it's a necessity. In this blog, we'll explore strategic approaches and practical tips to help you streamline your innovation process and ensure that your product reaches the market swiftly and successfully.

- Start with a Clear Vision

Before embarking on the innovation journey, it's crucial to have a clear vision of what problem your product solves and who your target audience is. Define your value proposition and ensure that it aligns with market needs. A well-defined vision serves as a guiding light, helping your team stay focused and make informed decisions throughout the development process.

- Embrace Agile Methodology

Agile methodology has become synonymous with rapid innovation. By breaking down the development process into smaller, manageable tasks and regularly reassessing priorities, you can adapt to changes swiftly. This iterative approach allows for continuous improvement, reducing the risk of late-stage changes that could delay your time to market.

- Foster a Culture of Innovation

Innovation is not solely the responsibility of the R&D department; it should be ingrained in the entire organizational culture. Encourage cross-functional collaboration, reward creative thinking, and create an environment where employees feel empowered to share their ideas. A culture of innovation promotes a collective mindset that can significantly speed up the product development process.

- Conduct Rapid Prototyping

Waiting until the final stages to test your product can be a costly mistake. Rapid prototyping allows you to gather valuable feedback early in the process, enabling you to make necessary adjustments swiftly. By incorporating user feedback throughout development, you reduce the likelihood of major overhauls later on, saving both time and resources.

- Utilize Technology and Automation

Leverage technology to automate repetitive tasks, streamline workflows, and enhance collaboration. Project management tools, communication platforms, and collaborative software can significantly increase efficiency. Automation not only accelerates processes but also minimizes the risk of human error, ensuring that your product development stays on track.

- Build Strategic Partnerships

Collaborating with external partners can provide access to valuable resources and expertise, accelerating the development process. Whether it's forming strategic alliances, outsourcing specific tasks, or leveraging existing networks, partnerships can help you overcome challenges and bring your product to market faster.

- Prioritize Minimal Viable Product (MVP)

Instead of waiting for a fully polished product, focus on delivering a Minimal Viable Product (MVP) that addresses the core needs of your target audience. Launching an MVP allows you to gather real-world feedback, validate assumptions, and make necessary adjustments before investing in extensive features. This approach not only accelerates time to market but also reduces the risk of building a product that misses the mark.

To borrow from management guru Peter Drucker, businesses have only two core functions, and innovation is one of them. By incorporating these strategies into your innovation process, you can position your business as a dynamic force in your industry, delivering products to market faster and staying ahead of the competition. Remember, the key lies not only in developing groundbreaking ideas but also in executing them swiftly and efficiently. Embrace innovation, foster a culture of agility, and watch your business thrive in the ever-evolving landscape of today's market.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

management

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Innovation on February 9, 2024.

Permanent link for Build Your MVP on January 5, 2024

Launching a new product is an exhilarating journey that demands careful planning, strategic thinking, and a deep understanding of your target audience. To fully understand your target audience, you have to put product in their hands. Rather than spending time and money building the better mousetrap, it's best to start with the creation of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a crucial step that can make or break your venture. How do you build a winning MVP?

-

Define Your Core Value Proposition: Before diving into development, it's essential to clearly define your product's core value proposition. What problem does it solve? How does it meet the needs of your target audience? The answers to these questions will guide the development of your MVP and ensure it addresses the most critical aspects of your product.

-

Identify Key Features: An MVP is not about including every possible feature but about focusing on the essential functionalities that demonstrate the product's value. Identify the features that directly contribute to solving the core problem. This laser focus ensures a quicker development process and allows you to gather valuable feedback sooner.

-

Keep It Simple and User-Friendly: Simplicity is key when creating an MVP. A clean and intuitive user experience not only attracts users but also allows them to understand and use your product effortlessly. Avoid unnecessary complexities, and prioritize a seamless user experience to encourage user engagement.

-

Build Rapid Prototypes: Prototyping is a powerful tool in the MVP development process. Rapid prototypes act as a tangible representation of your product, helping you identify potential issues early on and to iterate quickly as you learn what works and what does not.

-

Embrace Iterative Development: The MVP is not a one-time effort but a process of continuous improvement. Embrace an iterative development approach, releasing small updates and improvements based on user feedback. This not only keeps your product aligned with user needs but also demonstrates a commitment to ongoing enhancement. The frequency of updates and amount of development that goes into each iteration will depend critically the economics of developing, producing and testing prototypes.

-

Collect User Feedback: User feedback is the lifeblood of a successful MVP. Release your product to a select group of users, gather their feedback, and use it to refine and enhance your offering. Leverage feedback loops to continuously optimize your product based on real-world user experiences.

-

Measure and Analyze: Implement analytics tools to track user behavior and engagement. This data provides valuable insights into how users interact with your product, allowing you to make data-driven decisions. Metrics such as user retention, conversion rates, and user satisfaction are crucial indicators of your MVP's success.

-

Prepare for Scalability: While the focus is on building a minimum viable product, it's crucial to plan for scalability. Choose a robust architecture that can grow with your user base. Anticipate potential challenges associated with increased demand and have a roadmap for scaling your infrastructure accordingly.

Building a Minimum Viable Product is an exciting and transformative phase in the product development journey. By staying focused on your core value proposition, embracing simplicity, iterating based on user feedback, and planning for scalability, you set the foundation for a successful product launch. Remember, the MVP is not the end but the beginning of a journey toward creating a product that truly meets the needs of your audience.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

Posted

on

Permanent link for Build Your MVP on January 5, 2024.

Permanent link for Slow is Smooth; Smooth is Fast on November 10, 2023

Entrepreneurs and innovators exist in rapidly changing environments with high degrees of uncertainty and a need to move fast. Success often hinges on strategic thinking, resilience, and adaptability. There are other professions and organizations that face similar pressures, and which have been dealing with them for much longer. We can learn from them.

The Navy SEALs is one such organization, where the stakes are much higher than those entrepreneurs face. The SEALs are renowned for their mental toughness and ability to thrive in challenging environments. "Get comfortable being uncomfortable" is a mantra that resonates with the challenges of starting a business or launching a new product. Entrepreneurs can embrace adversity as an opportunity for growth.

Another principle that I am frequently reminded of is "slow is smooth; smooth is fast." When applied to manual operations like drawing a weapon or playing an instrument, it's an admonition to take the time to get muscle memory right and then let training make you fast. For entrepreneurs, it underscores the importance of careful planning and execution for sustained success. Get the process right; let process improvement make you fast.

Brent Gleeson, writing at Forbes, offers nine such sayings.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Slow is Smooth; Smooth is Fast on November 10, 2023.

Permanent link for Why new products and services fail on October 27, 2023

There are lots of reasons why businesses fail, but some reasons are more common than others, and many entrepreneurs bump up against at least one of these three:

- No market

- Team is missing key experience or expertise

- New product category, requiring extensive customer education

No market

Few customers will adopt a new product or service if they aren't experiencing a pain with existing solutions. Without a thorough understanding of your target audience's pain points, preferences, and behavior, you risk creating something that people simply don't want or need. This disconnect can lead to wasted resources, low adoption rates, and ultimately, business failure. Successful innovation starts with robust market research, customer feedback, and a deep understanding of the problem you're solving. Only by aligning your product or service with a clear market demand can you increase your chances of success, ensuring that your innovation meets real customer needs and creates value in the market.

Another incarnation of this failure occurs when the pain customers experience is so ubiquitous—so ingrained into everyday experience—that they don't recognize it as a pain. In such cases, the innovator needs to educate potential customers to get them to see the problem, recognize it as a pain, and perceive the new product or service as a solution.

Missing team expertise

A lack of diverse expertise within a startup team can significantly contribute to venture failure. Critical skill gaps often include financial expertise, marketing and sales expertise, and technical skills. Without these essential competencies, ventures may make costly mistakes, miss growth opportunities, or struggle to adapt in a rapidly changing market. Building a well-rounded team with expertise in these areas is crucial to navigating the challenges of entrepreneurship and increasing the odds of success.

New product category

Much like lacking a market, customers will often struggle with making sense of a new product that carves out a new product category. They will need to be convinced of the need for a product.

The Segway provides a classic example of the product category failure. Even on the company's website, the product has been variously identified as "personal, green transportation" and "small electric vehicle." Does the Segway compete with bicycles? Walking? The inventor said that the Segway would "do for walking what the calculator did for pad and pencil." In the end, despite abundant hype, the Segway just hasn't quite connected with consumers, and the evidence points to a failure of consumers to "get" the product.

How to avoid

- Try to intentionally test your business model against these failure modes

- Conduct thorough market research

- Work on being clear about the value proposition you're providing…from your customer's perspective

- Look for market, financial, and social trends that would make your idea inevitable, and get to market just ahead of the competition

- Be prepared to pivot

CB Insights did a big study that confirms the above, and Harvard Business Review have a slightly different take on why most product launches fail, and it's worth reading.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Why new products and services fail on October 27, 2023.

Permanent link for Fail fast on September 8, 2023

Much of my career has been spent developing new technologies and new products. One of the smartest people I ever worked for, a brilliant scientist, introduced me to the concept of "fail fast."

Up to that point, my approach had been mainly about trying different inventive ideas and seeing what worked. As a team, we would try to figure out what we did right, replicate that, and introduce the next Good Idea.

We had some good ideas. We also had lots of failures. Some of those failures were avoidable and many of them overshadowed the successes. Failure can be expensive.

The flexibility to make changes to a product or service decreases as we get closer to launching in the market. Decisions made earlier in the process become harder and more expensive to change. At the same time, as we approach commercial launch, we're spending more money on development and to acquire goods needed for launch. Potential failure points in our product or service design therefore become more expensive to fix as we get closer to launch. Figuring out why the good parts of an idea work doesn't make for more success, but finding failure points does.

The failing fast mindset accepts that while no idea is perfect, most ideas have merit with some weaknesses. In failing fast, we seek to exploit those weaknesses early in order to identify and either eliminate or mitigate them as early and as cheaply as possible. Instead of testing to verify possible success, test to find potential failure points.

Put another way: we want to learn as fast as possible. Fail fast means to deliberately test for failure points so that we can learn about and eliminate defects in our product, our service, and our business model.

To set up testing, identify the specific hypothesis you want to test. Then, create a test plan that outlines the steps you will take to test the hypothesis. For example, if you want to test whether a new website design will increase conversion rates, you might create two versions of the website with different designs and send half of the traffic to each version. Use A/B testing to measure the conversion rate for each version and use the results to identify which version performed better.

By adopting a fail-fast approach, entrepreneurs can quickly identify mistakes, learn from them, and make improvements. Remember, failure is not something to be afraid of. Instead, it should be embraced as an opportunity to learn and grow.

When developing new products or services, the costs spent on development increases, while the flexibility in making changes to the design of the product or service decreases. Image from NPD Solutions.

Categories:

entrepreneurship

innovation

invention

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Fail fast on September 8, 2023.

Permanent link for Product Cost Modeling, Target Markets, and Pricing on April 14, 2023

Entrepreneurs and intrepreneurs developing new products are inevitably asked "how much does it cost?"

To answer this, we need to distinguish between price—how much the customer pays—and cost—how much it costs you to put it in the customer's hands. We also need to distinguish between how much it costs right now and how much it will cost at volume.

If you're talking to potential customers, who are interested in buying, they really mean "what's the price, right now?" You'll need an answer for them, because you want them to buy. You need that market validation. So what's the right price? Ideally, it's a premium price point, but early price points should have no relation to actual costs. You're testing the market; not your operational efficiency.

If you're talking to potential investors or internal stakeholders, they usually want to know about the cost at volume. Volume is a bit tricky. You cannot possibly obtain an accurate cost estimate to produce a product design that doesn't exist yet in volumes you can only guess at, and at a manufacturing site that you haven't selected. But that's o.k.! You don't need to know the exact costs of every component; you only need to know which components of production drive the bulk of your cost, and roughly what those components cost at volume. What we're really looking for is just a fair estimate, at the highest volume that makes sense. If you're developing the next whiz-bang smartphone, where the total market is running around 1.5 billion units per year, you don't want to estimate volumes of 10 billion units per year. But around a hundred million a year could be the basis of a perfectly reasonable volume cost estimate.

Let's try an example of part of your operation. Suppose you're manufacturing your next-gen smartphone in China and shipping to the U.S. west coast once a month. Your product is small and you can fit 500 units to a pallet. Shipping rates for that pallet will probably run you around $1,000 (mid-2022 prices), or $2 per phone. When sales grow enough to utilize an entire 40-foot shipping container, you'll spend $10,000 but ship 20 pallets, or 10,000 units, lowering the cost per phone to $1. If you could reach volumes of around 120 million phones per month, you can buy the capacity of an entire container ship, which a google search or a phone call to a major shipper tells you will cost around $100,000 per day. With shipping times of around two weeks, you'd spend about $1.4 million per month to ship those parts, but the cost per part would be just 1 penny. When an investor or stakeholder asks you "how much will it cost," your answer should not be "$1,000 for a pallet of 500 phones;" your answer should be "we estimate 1 cent per phone at volume."

If your investors instead want to know how much it costs today, you'll of course tell them that at today's very low volumes, shipping costs about $2 each to port; just $500 per month.

One startup manufacturer I'm familiar with had a product where the bulk of the cost came from labor and certain metals in the product. That manufacturer's answer to "how much does it cost" assumed production would (someday) be someplace where labor was cheap and that volumes would be sufficient to buy an entire mine's-worth of metal production—this resulted in the lowest potential costs. In the present day, their actual costs were many times higher, with production in the United States where it was easier to manager during scale-up and with lower volume metals purchases.

This cost-volume relationship holds for just about every product or service that a business provides. The more you do, the more your costs are dominated by variable costs rather than fixed costs, and cheaper the variable costs get per unit.

For this reason, early-stage startups should (almost*) never be trying to sell into cost-conscious mass markets. You should be looking for the high-value customer segments, those who are willing to pay a premium price for a premium product or service. As your volumes increase, you can work on reducing costs and then reducing price while holding your margins (or letting margins slip while raking in large revenues, the way oil companies do). We'll cover this more in a future blog post.

* almost never: there are some great market opportunities in cost-conscious markets, where customers are under-served or not served and cannot afford current offerings. Startups can offer a lower-margin substitute with fewer features at lower prices, staving off competition from established companies while gaining market share. Examples include the early personal computer market, transistor radios, and shared mobility (e.g. Uber). Harvard Business Review offers some additional insight.

Categories:

innovation

management

Posted

by

Thomas Hopper

on

Permanent link for Product Cost Modeling, Target Markets, and Pricing on April 14, 2023.