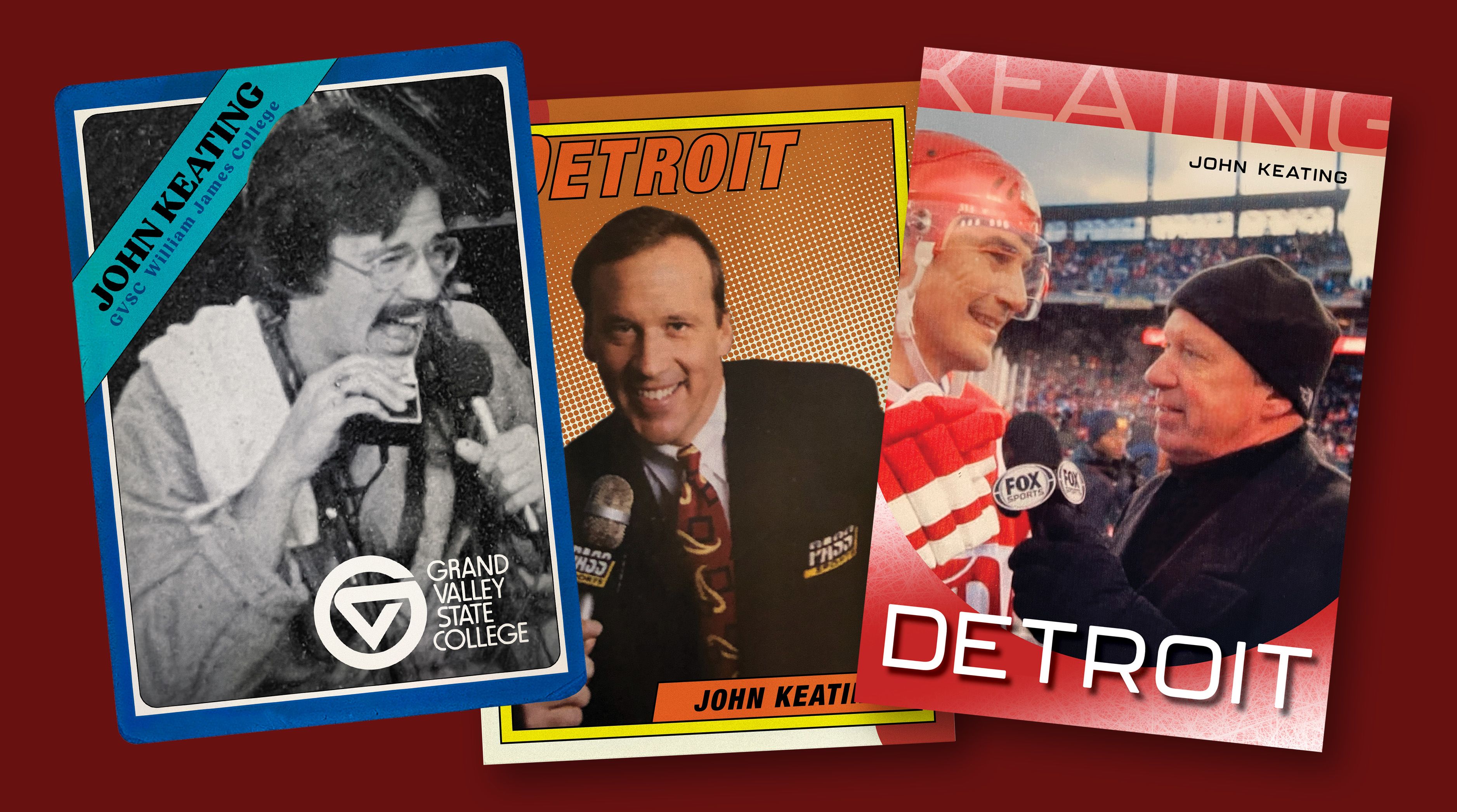

FEATURE

Spider Sense

A tiny arachnid helps a GVSU research team track chemicals in Michigan’s waterways

STORY BY BRIAN VERNELLIS

PHOTOS BY CORY MORSE

Under a blazing June sun, two Grand Valley graduate students tread through the shallow waters of the Flat River, a tributary of the Grand River in Lowell that runs through Montcalm, Ionia and Kent counties.

Wearing waders, biology majors Addison Plummer and Josie Kuhlman are on the hunt, slowly making their way along the shoreline’s shin-deep waterline.

While Plummer collects soil samples from the riverbed, Kuhlman examines any tree branches that overhang the gentle stream. Along this section of the Flat River, there are plenty. A bit of movement has caught her eye, so Kuhlman crouches to get a better look at the protruding branch.

“It led us to start asking questions out of curiosity.”

Ryan Otter, interim vice provost

of Research and Innovation

Eventually, after collecting enough soil samples, Plummer joins the search. Their quest? A spider — the long-jawed orb weaver — that is key to the research of Ryan Otter, a professor at the Robert B. Annis Water Resources Institute, who was recently named as the interim vice provost of Research and Innovation.

“The biggest ones are about the size of your middle finger’s fingernail,” Otter said. “Then their front legs are probably twice the size of their body length, probably even longer than that. They're long and skinny.”

Despite its diminutive size, the arachnid plays a monumental role in his research across several fronts. Since his time as a doctoral candidate at Clemson University, Otter has been studying the spider’s function as a bioindicator in the ecological health of the nation’s waterways.

“At first, when I was a doctoral student and got involved, I was surprised,” Otter said. “These results that came out didn’t make any sense.

How could a spider that’s eating aquatic bugs have all this pollution?

“It led us to start asking questions out of curiosity. Once we realized the data was solid, and that this is actually what’s going on, it’s what drives me and a lot of the research teams I work with.”

His data is helping his fellow biologists, ecologists and environmental scientists get a better understanding of how synthetic chemicals and industrial byproducts accumulate and linger in the Great Lakes, Michigan’s water, and ultimately, its residents.

His work is also shedding light on whether remediation efforts at some of the nation’s most polluted rivers and lakes are making a difference.

Tracking toxins

Otter’s research examining contaminants, such as mercury and industrial chemicals, in the water has extended for nearly 20 years. After serving in an administrative role at Middle Tennessee State University, Otter said he was eager to return to hands-on research in the classroom, his lab and the field.

“One big reason why I wanted to move to Grand Valley was because I value the Great Lakes resource that we have,” Otter said. “Plus, it was the ability to bring my expertise and create a team of Grand Valley students and staff to work on Great Lakes projects from the AWRI, which sits on Muskegon Lake.”

Ryan Otter holds a long-jawed orb weaver spider on the Valley Campus.

Ryan Otter holds a long-jawed orb weaver spider on the Valley Campus.

At first glance, the long-jawed orb weaver spider may seem like an unlikely candidate to anchor years of ecological research, but Otter is quick to point out its many scientific advantages.

The spider, a member of the Tetragnathidae family, and its relatives are ubiquitous on the planet. The orb weaver is found on every continent, except Antarctica, said Otter, and yet, thanks to its natural camouflage and nocturnal habits, it often goes unnoticed.

“They're most active at night,” said Plummer. “You can find them during the day, and they blend in with the sticks that they live on. They just become very skinny and long.

“If you shake a branch, you can see them start to crawl and try to get away because they think the wind is shaking the branch.”

Otter added: “In terms of monitoring and assessing specific areas, we need something that's area-specific and these spiders are really good at doing that. I've taken undergrads who have never been in the field before, and we'll collect 300 in a night.”

For most of its short life — Otter estimates most orb weavers have a lifespan of about a year — the spider spends it within a small geographic area. Their non-nomadic life and short life span make it easier for Otter and other scientists to track pollutants.

“When you collect a spider, what you're looking at is information from right now,” he said. "If you count a fish, that fish might be alive for as many as 10 years. Because fish swim around, you don't know exactly when and where that pollution got into the fish.”

Because of its global presence, the spider also sits at a key junction within the ecosystem’s food chain.

Addison Plummer, left, and Josie Kuhlman prepare to collect samples from the Flat River.

Addison Plummer, left, and Josie Kuhlman prepare to collect samples from the Flat River.

“What makes them the most useful for monitoring water pollution is what they eat,” Otter said.

Aquatic insects, like mayflies, constitute the bulk of the orb weaver’s diet. When the insects reach maturity, they undergo a metamorphosis similar to a caterpillar, Otter said, growing wings and leaving the water for reproduction.

In preparation for their meal, the orb weavers make their way to the ends of over-hanging branches and spin thin webs, parallel to the water surface. As the insects emerge from the water, they’re snagged in the web.

Not only is the spiders’ role as predator important, but so is its role as prey.

“My major concern and research has not been about spider health,” Otter said. “It's about using them to understand the movement of pollution and, in this case, there are a lot of things that eat spiders. Birds and bats, some of which are threatened and endangered, eat high proportions of spiders in their diet.”

Plummer said most concerning is the way contaminant levels progress and amplify through the food chain.

“Birds can eat the spiders and then have higher concentrations of mercury than what was even found in the spider,” she said. “It’s the same with fish. Fish can eat these insects and have higher concentrations of mercury.

“That’s why we're wanting to see how, where and when the pollution moves and why it elevates up the food chain like that.”

Tiny spiders,

big clues

In addition to the orb weaver’s environmental value, one physiological trait makes it especially significant for Otter.

“They're small, but they’re power-packed, little packets of fat,” Otter said.

Lipids, or fats, play a critical role in storing energy, but Otter’s concerned with one of their aspects: the ability to absorb and retain contaminants. Once embedded in fatty tissue, many of these toxins become difficult for a body — spider or human — to metabolize or eliminate, leading to long-term accumulation.

“The reason why we are worried about most water pollution as humans is usually because it follows along in our fat,” Otter said. “This is why things like PCBs are considered to be really dangerous for things that live on the top of the food chain, like humans.”

Despite being banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1979, PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl) has lingered in the nation’s waterways. The chemical was widely used as lubricants and coolants in electrical equipment.

Recently, Otter has expanded his research. He and his colleagues published their findings on the effects of metals like dioxins and furans, the byproducts from the pulp and paper industry, and in the production of herbicides.

“It’s been a journey that I never thought I'd get a chance to do in my whole science career,” Otter said. “To see something from inception to utilization, and now it’s utilized in different countries, keeps me motivated to keep advancing the science because we do think that it's very useful in the real world.”