A Day in the Arctic

Morning at the Nest

It’s mid-season by now. In Utqiaġvik (formerly called Barrow), we wake up around 8am. Each of us creeps out of our rooms, desperate for coffee. There’s a communal pot by the sink, and if we timed it right, there might be enough left to kickstart the first person up from our crew. By this time in the season, we’ve decided to offset our schedule from the rest of those calling the Nest home for the summer. The kitchen gets crowded during mealtimes, and avoiding the chaos of cooking is always nice.

The first one of us up, usually myself, makes coffee for the rest of the crew. I bring my laptop to check my email and back-up pictures while I wait for the pot to brew. Clair and Scott come out a little while later, and slowly we start making breakfast. I make oatmeal with protein powder, Clair has fruit and yogurt, and Scott, usually an egg and bacon sandwich. We’re all dragging a bit this morning, but the weather looks to be a balmy 45 degrees with blue skies, a great day in Utqiaġvik. We have breakfast and decide to leave around 9:30. We have a full day ahead of us. I send an email updating Bob on the week’s progress while the others finish eating. Everyone packs a lunch and puts on their coats and gear. We meet in the boot room and leave the Nest.

The Nest

The Ukpik Nest II is our home away from home during the summers. Ukpik is the Inupiaq word for the snowy owl, a common site across the tundra and at the ITEX sites outside Utqiaġvik. The nest is a former dormitory that oil executives used in the early 2000's while looking into oil production in the North Slope. After the project was scrapped, UIC repurposed and remodeled the building to house scientists and others coming to work in Utqiaġvik.

Kitchen at the Nest

We share this bank of ovens and refrigerators with several research groups during the summer. Cooking can be challenging because of the cramped space so being courteous towards others is very important!

Video tour of the Nest.

Video Credit: Ale Martinez, PolarTrec educator

To the BARC

It’s a short drive to the BARC (the Barrow Arctic Research Center). The BARC is the lab space set up by UIC (Ukpeagvik Iñupiat Corporation) that hosts scientists during field seasons. Each group rents a lab space for the summer and sets it up for their work. Our research isn’t particularly lab heavy, so we use the space to organize our data books, prep gear and work on data entry when we need a big space. We make our way to our lab room to grab supplies for the day. Scott gathers up the tram supplies and batteries while Clair and I grab our books. Today, we’re doing growth measures and flower counts on the ITEX plots. Clair grabs the flower count book for the wet site. I grab the dry site growth measures and a ruler. We make sure to bring along good clipboards to mitigate the wind and even better kneepads for the long day of kneeling ahead of us. After a handful of gummy bears (courtesy of Bob), we’re off.

We drive from the BARC, the Beatles Revolver album playing on the radio, and weave through the roads of the NARL. Our sites are spread along a drained thaw lake just south of Point Barrow and the Arctic coast. To get there, we drive through the DEW line station, down a one lane dirt road, and park at the Utqiaġvik NOAA building—one of the clean air observatories for the U.S. We back into our spot on the turn-around and walk out.

The BARC

The Barrow Arctic Research Center, owned by UIC science, provides laboratory space for the scientists visiting the North Slope. Here, we stage our gear for the season and work on data when we need a larger area.

The DEW Line

The DEW line (Distant Early Warning) is a line of military installations that were built in the mid 1950's to provide warning of possible incoming attacks by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. This one, outside of Utqiaġvik, AK, still houses military personnel year-round.

The NOAA Building

The NOAA Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory is the northernmost air, weather, and climate monitoring station in the U.S.

Our sites in Utqiagvik sit just a bit south of the station and the fine folks at NOAA let us park outside their station to minimize our hike out.

Walking Out

The walk to the sites is always nice. The snow has long melted away by now and the colors of the tundra are showing through. Lichen, moss and dwarf willows cover the ground in a beautiful array of yellow, green and red hues that almost glow under the sun and fog that roll through. There’s a snow bunting nest under a section of boardwalk near the first chunk of the dry site. Here, Scott passes the tram gear to Clair to drop off at the third boardwalk for later. He and I head up the first section of the dry site to start the week’s growth measures.

Path to the Dry Site

The tundra at the ITEX sites in Utqiaġvik. It is technically a desert based on rainfall volume, but also a wetland based on squishy wet soil. The tundra here is filled with bright colors this time of year. Here, you can see a wide variety of plants, lichen, and mosses that fill the landscape.

Snow Bunting

A snow bunting chick peaks through the board walk. The birds grow up quickly in the Arctic, so we were able to avoid this section of the boardwalk while the chicks grew up. After a week or two, the chicks were finally large enough and flew off.

Growth Measures, Flower Counts

Growth measures are exactly what they sound like. Each week, we record how long the biggest leaf and/or flower on an individual plant is. We only measure graminoids (the grassy looking species including sedges, rushes, and of course grasses). Each species has three individuals marked that we’ve followed through the years. It’s a tedious process that yields a massive dataset showing how the plants are growing. More importantly for a field tech, though, is that this measurement gives you incredible familiarity with the plots. Partway through the season, you’ve adopted these plants as your own and by the end, you probably know where every single tiny plant lives within each plot. They can be tricky, though. Thin leaved Poa species can sometimes disappear in a light breeze, and the orange-ish leaves of Luzala confusa can easily blend in with the backdrop of soil and standing dead from previous seasons. Even with the sticks marking them, growth measures can be challenging. Each previous AEP member always refers to a certain site as “my site”. Though I’m working at the dry site in Utqiaġvik this summer, I always think of the Atqasuk wet site as “my site”. Even after not working it for a few years, I remember each of the plants well. They’re your plants, after all.

By now, Scott and I have developed a routine to smooth out the lengthy process of growth measures. I kneel on my kneeboard in front of the plot, scanning from corner to corner looking for each stick. “LARC 2!” I say.

Scott replies “4.2”, the previous week’s measure.

“4.8” I reply. This is the new leaf length. “CARSTA 3?”

“6.3”

“7.1”

And on and on until the plot is done. You might have noticed the strange words here don’t align to much of anything plant related. Those words are some codes to a few of the species we work on here. Each species has a four and six letter code tied to them by genus and species. So, here, LARC 2 is the code for the second marked individual of Luzula arctica and CARSTA 3, the third marked individual of Carex stans. These codes extend across all measurements and help us shorten the time spent on complicated scientific names in an area where it can be hard to hear someone next you over the constant wind. Like all data in ITEX, these codes are part of a master dataset with all other plant information tied to that code. This way, all the data can be kept brief and tidy for analysis later on.

After each marked individual is recorded, the largest individual or the first one with a flower (inflorescence, more properly) is recorded. These individuals can change from week to week, depending on flowering time and growth rates. During all this, Scott will also record any changes to phenology that I notice while going through the plot. Maybe I notice only a single new flower open here or there, or a new plant popped up through the soil, but each development is crucial. It’s important to use the books together to keep everything consistent. At the end of the season, all the dates are compared and inconsistencies are flagged and corrected. Getting data right in the books is the most important thing an AEP member can do to make the work successful. After each species is measured and recorded, we move on to the next plot.

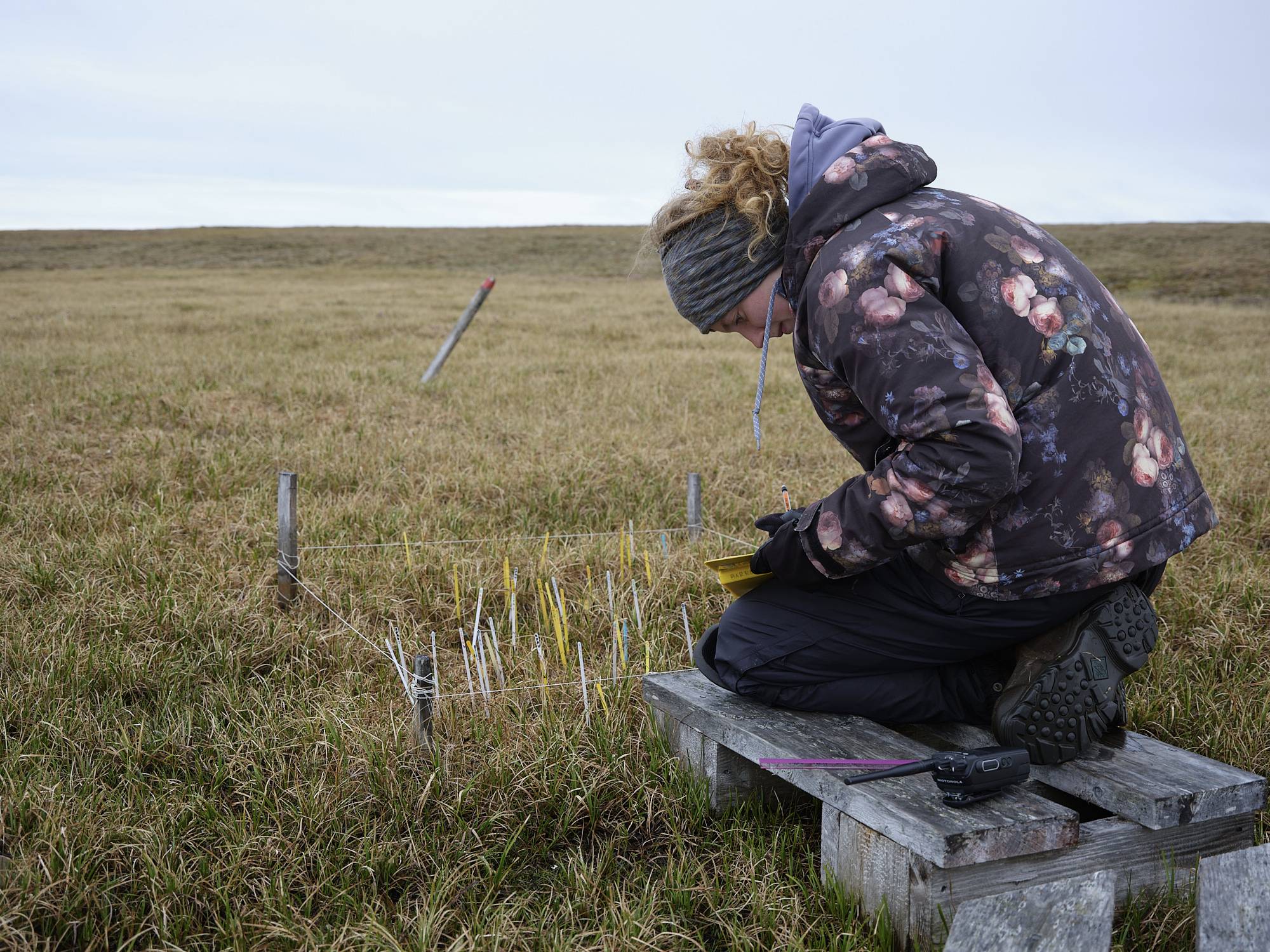

Clair measuring plants at the Barrow wet site.

Each week of the field season, we record the leaf length of 3 marked individuals from each graminoid species in the ITEX plots. Each individual is marked with a white stick with a four-letter species code. Yellow sticks represent shrubs and forbs that we record data on at the end of the season.

While we run through growth measures at the dry site, Clair is down at the wet site recording her flower counts for the week. By this point in the season, each type of plant is flowering in full force. The wet site in Utqiaġvik is filled with a large variety of forbs. Yellow Ranunculus nivalis fill in the gaps between sedges here and there, and purple balloon-like flower heads of Melandrium (apetelum) mix in with a mat of bluish Poa. While counting flowers seems like a breeze, we also use this measurement to record the different stages that each flower goes through. In mid-season, it can be intense. We count pre-flowers (tiny buds that haven’t opened yet), open flowers (flowers that have opened or produced yellow anthers or stigma), withered flowers (those that have reached seed or have died off), and flowers that have been eaten. During peak-season, each species might have dozens or hundreds of flowers at any of these stages all at once. Recording the stages gives us two advantages—one, being able to cross-reference each stage with phenology and earlier season measurements to check for mistakes, and two, allowing us to compare the timing and amount of reproduction happening to a given species in a given plot across many years.

Each week, these numbers should grow. Sometimes, finding a tiny Poa inflorescence can be tough among a sea of taller grasses. It’s a game of needle-in-a-haystack, except the needle is a different color of hay, and the whole haystack is swaying in the breeze. Needless to say, we can go a bit crazy staring at the plots all day, but it is all worth it in the end. Nothing trains your focus better.

Ranunculus nivalis (the Snow Buttercup)

A stand of Ranunculus nivalis flowering near the Utqiaġvik wet site.

If you look closely, you might be able to spot an old lemming trail cutting through the patch.

Carex subspathacea

Tundra plants are notoriously small and this fact can sometimes make measurements a challenge. This Carex species is a great example since their full height is only a few centimeters tall! Could you find this in a patch of grasses?

Wet Site Control Plot

This is what a fairly typical wet site plot might look like. Though we call the measurement flower counts, we also count inflorescences too. An inflorescence is just a compound flower like those you might find on a dandelion (vs singular, like on a lily). Grasses, sedges, and rushes have this multi-flower structure and can make up the bulk of our measurements in some plots.

Click the above image for a high-resolution version. Can you find all the inflo's in this plot?

At around 1p.m. everyone heads to the tent for lunch. Scott and I have just made it to the third boardwalk of the dry site, roughly plot 17. We radio Clair to check in and she comes up for lunch. We hang out in the tent and warm up a bit. Lunch is usually a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, Pringles, and a Snickers bar. The sugar and calories are helpful when most of your day is spent moving through the tough terrain of the tundra, so we bulk up when we can. At the end of the last summer, we went through so many cans of Pringles that we filled a garbage bag while packing up! They came in handy though. It turns out that an empty Pringles can is the perfect size for a single soil core. We ended up using most of them to store and ship cores for a different project. Who knew.

The Tent

By the time lunch rolls around, our hands and toes are usually just about frozen. So we take the opportunity to get out the wind and hide in the tent while we eat. We set it up close to the MISP so that we can run the tram at the same time.

Taylor in the tent

We use Arctic Oven tents during our field season. They're great for drying out after a long morning of work and perfect for hiding a stash of pringles or extra gear for when you need them most. Plus the tents make everything inside look orange, maybe helping to trick your mind into believing it's not as cold as it is.

The Tram

During our break, Scott walks over and starts the tram. Well, we call it the tram. Its technical name is the MISP (short for Mobile Instrument Systems Platform). It is loaded with sensors and hangs on cables between two towers to record a 50m transect of undisturbed tundra.

Running the tram is a daily task, and it can be finicky. One of us sets up all of the instruments, attaching cables, and making sure the datalogger is playing nice with a laptop that rides along. Oftentimes, the spectrometer doesn’t cooperate, or a cable breaks. During the winter, the tram lives in a semi-heated storage building but even with careful storage, technology does not get along with the cold. After everything is checked and setup, we press ‘record’ on the 3D Fujifilm camera and recite the days conditions for the video of the transect:

“This is Justin Blough running the Barrow tram. It is July 17th, 2024 at 1:25 p.m. The temperature is 45 degrees, humidity is 50%. Wind is a constant 5mph with blue skies and no clouds in sight. Have a nice ride and see you on the other side.”

We usually record a little sign-off at the end, because, why not. After reciting the conditions, we turn on the drive-cable motor at the tower and send the tram off on its way. The tram moves about 10cm every three seconds so that gives us a good reason to take a long lunch. While it runs, we record the time the platform arrives at specific points along the transect, including start and stop times in a dedicated Rite in the Rain notebook. By tracking these timestamps, we can align all the various onboard data sources to combine or compare later on. Back at the lab, we back-up all of this data and send it off to Jeremy for quality checking.

Scott running the tram in Utqiaġvik

The tram is an important part of ITEX-AON. It records a host of data on the plants below that we can use to determine community structure and tundra health.

The MISP tram can also be used as a intermediary between plot level measurements and wider scale data collected by either drone or satellite.

Once the tram is finished, it’s time to go back to work. Occasionally a fox shows up near the third boardwalk of the dry site. This particular boardwalk is a great place to hunt lemmings, and he knows it. Seeing us, he gets distracted. He runs around, chewing at the boardwalk and any object in reach. He circles through the site, checking us out, making some half steps forward before lunging backwards at any movement from us. They seem friendly, almost like puppies, but don’t let them fool you. The playful attitude and curiosity are often accompanied by rabies so it’s important to keep your distance. Scott finally chases him off, yelling and clapping until it gets bored and leaves to chase birds further off on the tundra.

A Fox Visiting the Dry Site

An Arctic fox chews at equipment at the Utqiaġvik dry site. Foxes can be a problem in Utqiaġvik. Even though playful, they frequently have rabies and can easily spread it to local dogs.

A few hours later Scott and I have finished at the dry site. With the week’s growth measures complete, Scott radios down to Clair. She’s on the last plot, finishing up a count of Melandrium flowers. Tomorrow the tasks will be reversed, and I’ll record flower counts on the dry site.

Clair at the Wet Site

Clair recording data at a particularly packed plot at the wet site. Each stick corresponds to a marked individual of each species. White sticks represent graminoids, the grassy species we perform growth measures on. Yellow sticks represent shrubs or forbs.

Back at the Nest

It’s about 7 p.m. by the time Clair meets us at the dry site. Scott and I gather our gear and we all head back together. We stop by the BARC, drop off our kneepads and charge the tram batteries, and finally head home. By the time we get to the Nest, there’s only a few people left hanging around the kitchen. We’ve timed it again so that we miss the dinner rush and the crowd around the ovens. Scott is our resident chef, and tonight is an enchilada kind of night. We help mash pinto beans and mix spices, then Clair and I sit in the cafeteria with the crew from UTEP while Scott puts the pans in the oven. While we wait, we play cards. Hearts is the game. Scott wins, as usual. Counting cards, whatdyagonnado.

Scott making enchiladas at the Nest

Since food is so expensive to get in Utqiaġvik, most people that live here primarily live off the land. For us researchers, that is a bit tricky. Instead, we ship up most of our food and supplement what we can from the grocery store in town. Beans are an easy protein that we cook with often.

We eat and hang out in the cafeteria for a while. Sometimes, we’ll take a walk across the road to the beach. The Arctic coast is one of the most beautiful places I’ve seen with black sand and ice floating through the water. In the later parts of the summer, jellyfish can be found floating close to shore. If you’re lucky, you might see a polar bear off in the distance. We head home. At around 9, we put on a movie and enter the day’s data.

Taylor in the Nest

Taylor Doorn is the longest current term member of the Arctic Ecology Program at GVSU. He predominately works in Atqasuk, AK. At the end of the season, we all ship out to home together from Utqiagvik but spend the last week hanging out as a group in the Nest.

The Coast of the Arctic Ocean.

In Utqiaġvik, we stay right across the road from the ocean. Here, the whole coastline is made of black sand and lined with ice often up until mid-July.

Night Talks

We usually disperse one by one for the night. Some nights I stay up later and talk to whoever wanders through, others I’ll sit out and catch up on data and project work in the cafeteria. There are people from all over the world staying at the Nest in the summer, and late nights in the Nest cafeteria are perfect for conversation. People tend to let their guard down after a day of fieldwork and often are open to any prying about science, especially by eager grad students looking to learn. I’ve met scientists from Russia, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, Mexico, and other innumerable places around the world in the cafeteria of the Nest. Most of those spending time there are students, but some occupants have decades of research under their belts. Some of my favorite interactions have been with people like this, who started out in vastly different fields before moving to Arctic work. Once, I met a man from New Zealand who started his science career working on Kiwi birds, lived and worked in Bolivia for multiple years before moving to the States and publishing a book on his time with the tribes there. Another time, I spoke well into the small hours, discussing the similarities and differences between the U.S. and Russia with a man raised in the latter. Living and working in a research hub like Utqiaġvik is a special opportunity for conversations like these. Everyone in the Nest has a little bit of the same mix of drive, intelligence and peculiarity.

At night, the sun shines right into the windows of the Nest and the whole cafeteria glows from the reflections around the room. It is easy to lose track of time, and it happens often. The late hours offer a good chance to catch up with early risers or night owls back home (time depending, of course) and get a good dose of the familiar. 1am is probably the best time to be awake in Utqiaġvik. Just make sure to get a picture. Everyone loves to see the midnight sun.

Midnight on the Arctic Ocean

This picture was taken at around 1am on one of the last days of our 2023 field season in the Arctic. The sun typically doesn't go down during our time in Alaska, but it does get a bit darker in August. This is about as close as it gets to sunset in the summer months.