Life in the Tundra

The tundra biome is characterized by low temperatures, little nutrients, short growing season, low precipitation, and presence of permafrost. Permafrost is a layer of ground that is permanently frozen (in other words frozen all year round). Most notably tundra is treeless because it is too cold. The rule of thumb is trees occur when the average summer temperatures (July or January) are above 10 degrees Celcius or 50 degrees Fahrenheit. There are two main subcategories of the tundra biome: arctic tundra, and alpine tundra. Arctic tundra is found in the northern hemisphere North of the Arctic Circle along the northern coasts of North America, Europe, Asia, and some of Greenland. The North Slope of Alaska (where the ITEX-AON research occurs) is considered arctic tundra. Alpine tundra is found at high elevations in the mountains all over the world (above tree-line). Tundra also occurs in the Southern Hemisphere, while most is alpine tundra, Antarctic tundra exists in ice-free places along the continent and on Antarctic and subantarctic islands; in Antarctica very few vascular plants exist (none historically but now there are a few especially near research stations) and the vegetation is almost exclusively bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) and lichens.

Although the tundra is considered one of the most harsh biomes on earth, life persists, and many people, plants, and animals call tundra their home.

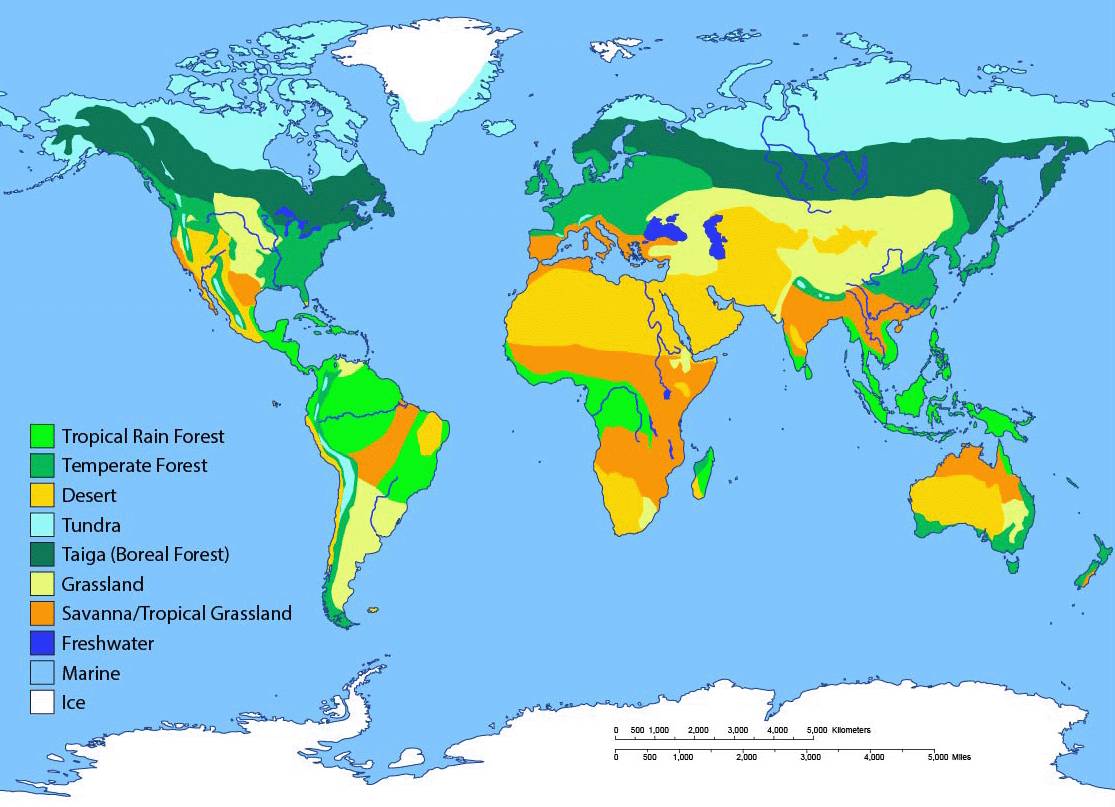

Biome map courtesy of Arizona State University. The tundra biome is highlighted in teal (although Antarctic tundra to small to see).

People

The people who inhabit the Arctic are resilient. Most of the people in the Arctic of North America are still a subsistence based culture. The Inuit (Inupiat in Alaska) population have a history extending back to the formation of the Bering Strait land bridge, and while other tribes inhabit other areas of Alaska the Inuit remained on the coast of the Arctic Ocean. Coastal populations largely get their food from the sea. Bowhead whale are a hallmark of their diet, consuming every part of the whale, and distributing it to the entire community. The villages in the Arctic are very community based, with a large respect for each other and the land they inhabit.

The people have lived harmoniously with the land and adapted to the conditions that it provides. Living in the Arctic is not easy. Indigenous knowledge is critical to the successful implementation of research. Residences provide the must useful logistical support and are a source of natural history for the region. For example, whaling captains in Utqiaġvik have assisted scientist in studying Bowhead whale populations for decades, and as a result Bowhead whales off the coast of Alaska are one of the best studied whale populations in the world.

Foraging of berries and greens has significant cultural significance, they are also a good source of micro-nutrients in an otherwise meat dominated diet.

Landscape

The Arctic has a beautiful landscape, and on sunny days one can see for miles. The North Slope of Alaska is flat and rivers meander in S-shaped patterns as they all flow towards the northern seas.

The Arctic can be categorized in two different types: low Arctic and high Arctic. The high Arctic is a more barren ecosystem, in generally have bare ground and the vascular plants are short and are often restricted to areas protected from the winds such as depressions and the lee side of hills, whereas the low Arctic is composed of tall shrubs and has higher biodiversity. Throughout both types of Arctic, permafrost exist and controls hydrology. Permafrost is continuously frozen ground that stays frozen for over two years.

The area above the permafrost, where plants roots may develop, and below the soil surface is referred to as the active layer. The freeze-thaw process of saturated soils results in cracks that then fill with water to create ice wedges, as these ice wedges accumulate across the landscape they create polygonal patterns. These polygons may be referred to as low or high center polygons. Low center polygons have a center that is lower elevation than the edges and typically have saturated soils and water on the surface. High center polygons have centers that are raised or similar elevation to the edges, they generally occur in areas that are drier and the center of the polygons are typically heavily vegetated.

Permafrost can be between 90-600 meters deep, being closer to the soil surface as you increase in latitude throughout the North Slope. In areas where the permafrost thaws and degrades thermokarsts may occur. Thermokarst is the degradation of soil that typically occurs in the form of mudslides or sinkholes. This can be a serious issue for those that inhabit landscapes with permafrost. Structures (building and houses) are raised off the ground on legs to prevent heat from the structure from raising the temperature of the soil and facilitating permafrost thaw. Roads overlain on permafrost can be destroyed quickly by permafrost degradation and can be an expensive problem.

Most villages occur on the coast. Sea ice is generally present throughout the winter, however, it has been melting quickly and occasionally there may be open water temporarily during the winter. During the summer the ice drifts away with the winds, it may return throughout the summer depending again on the winds. Many different species rely on the sea ice such as seals and polar bears. It has been predicted that the Arctic Ocean will be entirely ice free by the summer of 2050. Recently commercial shipping is possible because most of the Arctic Ocean is ice-free most of the summer and the ice that does exist is generally much thinner than it used to be. Before the 1980s it was common to find 10 year old ice, now most ice is annual ice, and more than 3 year old ice is rare.

Coastal erosion issues are accelerating quickly for most villages. Not only is the coast exposed longer due to a longer ice-free summer, the fetch is greater which creates larger waves, and storms are becoming more frequent and more powerful.

Plant Life

Vascular plant species diversity is very low in the arctic; you may have noticed the tundra doesn't have any trees - but why?

Sitting just above the deep layer of permafrost is the active layer, a shallow layer of soil that thaws during the summer. This thin layer does not provide adequate support for large trees, but the roots of smaller plants like grasses, shrubs, mosses, lichens, or other flowering plants don't need much to grab on to.

Plants that can survive in the Arctic typically have other adaptations to aid them with survival in the harsh tundra. Adaptations are adjustments of organisms to their environment which increase their chances of survival and reproduction.

The plants in the Arctic survive and grow in extremely harsh conditions. They are adapted to the cold temperatures and short growing seasons. In the higher latitudes the snow melts around the end of May and beginning of June returning in September with mean summer temperatures around 5-8 degrees Celsius in the more northern coastal areas. The soils are generally acidic and often low in available nutrients.

Every plant has their own unique strategy to deal with the environment. For example, Arctic Wintergreen (Pyrola grandiflora) takes several growing seasons to produce a seed, investing smaller amounts of energy into reproduction and more into protection each growing season. Some plants have relationships with fungus in their roots, known as mycorrhizal association, in which the plant gets nutrients from the fungus and the fungus receives energy from the plant in the form of sugars. This is another way that plants are able to survive in the cold, however not all adaptations must be so dramatic. Some plants take a simpler approach by simply growing closer to the ground (where it is generally warmer).

The air temperature is actually warmer closer to the soil surface than it is several feet off the ground, so species like the Cushion plant (Diapensia lapponica) benefit from being shorter and smaller. The same plants often grow very tightly together to reduce wind stress. Some plants appear fuzzy, which are pubescent hairs that grow to protect against the wind and to better retain moisture. Another way of beating the wind is to hold on to the leaves from the previous growing season like the Least willow (Salix rotundifolia), which help protect the plant. Another relatively simple adaptation is to grow darker leaves, which more readily absorb radiation than lighter leaves and thus require less energy to stay warm.

You’ve heard of some pretty interesting ways that plants can defend against the cold and survive, but these last two examples are very cool. The first is to get your energy from other plants. This is done by parasitic plants, which essentially graft their roots together with a host plant. The wooly lousewort (Pedicularis kanei) is a parasitic plant in the Arctic that commonly uses the willows as hosts. They obtain soluble sugars from the host plant, supplementing energy they can’t get through photosynthesis. The second very beneficial adaptation is a phenomenon known as “supercooling”. This is something that plants do to prevent themselves from freezing during the colder months. The important things to note are that the plant lowers the water concentration in their cells while also producing proteins to stop the formation of ice and other compounds that help to resist the cold. Essentially the plants produce their very own anti-freeze to stay alive.

Animal Life

To survive the freezing cold temperatures, animals in the arctic have developed a number of useful adaptations. According to Allen’s Rule, animals that inhabit colder regions will have a lower surface area to volume ratio. This means that generally animals in the Arctic have stockier builds to prevent heat loss. Every animal on the tundra is also covered in either fur, fat, or feathers to help keep them insulated.

Large Arctic mammals such as Caribou tend to have the ability to thermoregulate specific body parts. Oftentimes using their legs, they can pull heat to their core body, allowing them to survive cold temperatures when fur and fat just isn’t enough. This additionally helps conserve heat because limbs will lose heat quicker than the core body. If an arctic mammal were to find itself too warm on a summer day, this ability can be used in reverse, dumping core body heat into the legs.

Small arctic animals can find help from an unlikely ally - the snow. In the winter time, small animals such as lemmings will build systems of tunnels under the snow. This allows them to get around without being noticed by predators, dig deep into last season's grass to eat, and the snow actually acts as an insulative material, keeping them warm throughout the winter.

To escape the cold, some animals in the Arctic simply hibernate just like animals in the lower 48. However, the extreme freezing temperatures pose a new risk. The arctic ground squirrel has risen to this challenge, and adapted a way to allow its body to super cool to temperatures below freezing. It is hypothesized that they cleanse their own blood of impurities to prevent water from having anything to form ice crystals on.

When you can fly, escaping the cold is a better option than surviving in it, and so many bird species do just that. Arctic birds will mate in the tundra during the summer, then return to places all over the world in the winter. They prefer coastlines, including the great lakes, but will travel to other continents depending on species. The Arctic Tern has the longest migratory route in the world, migrating from north pole to south pole every year.

[1702680074].jpg)

[1702680094].jpg)

[1702934903].jpg)