Interfaith Insight - 2021

Permanent link for "Appreciative knowledge helps build bridges" by Doug Kindschi on August 10, 2021

“Americans are highly religious but have little content knowledge about religious traditions – their own or those of others.”

So wrote Stephen Prothero in his best-selling book, Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know – And Doesn’t. His recommendation was that more education about religion be taught in our schools from an objective perspective, “leaving it up to students to make judgments about the virtues and vices of any one religion, or of religion in general.” Hardly any school boards adopted his suggestion, and in many places, the “objectivity” of the teacher would have been a significant issue.

Eboo Patel, founder and president of the Interfaith Youth Core, in his book Interfaith Leadership, takes issue with “just the basic understanding of other religions.” In the interfaith agenda, we are not just dealing with abstract systems or textbook knowledge, he argues, “but actual people interacting in real-world situations.” He calls for an “appreciative knowledge” of other traditions, actively seeking out “the beautiful, the admirable, and the life-giving rather than the deficits, the problems, and the ugliness. It is an orientation that does not take its knowledge about other religions primarily from the evening news, recognizing that, by definition, the evening news reports only the bad stuff. … By being attuned to the inspiring dimensions of other religious traditions, such ugliness is properly contextualized.”

Patel’s whole approach is to build bridges between people and communities across religious lines. Beautiful examples of such occurred in the past years (prior to Covid) when the At-Tawheed Mosque and Islamic Center sponsored a “Know Your Muslim Neighbor Open House.” Hundreds attended and had the opportunity to visit the Prayer Hall, try on a Hijab, write their name in Arabic, and ask questions to refugees, teens, and women and men of this community.

A similar example occurred when the Jewish community at Temple Emanuel sponsored its “Taste of the Passover” with a light meal and a sampling of the traditions of the Passover Seder. It included holiday music and reading, an opportunity to ask questions and learn more about this important Jewish holiday. We look forward to resuming these in-person events in the future.

Appreciative knowledge also involves the learning of important contributions to our current society and throughout history from the various religious traditions. How many of us know that the architect of the Sears Tower (now the Willis Tower) and the John Hancock Center in Chicago was a Muslim? Fazlur Rahman Khan, the architect known as “the Einstein of structural engineering,” was born in Bangladesh where he received his bachelor’s degree in engineering. He immigrated to the United States where he pioneered a new structural design that initiated the renaissance in skyscraper construction during the second half of the 20th century.

Khan advised engineers never to lose sight of the bigger picture: “The technical man must not be lost in his own technology. He must be able to appreciate life, and life is art, drama, music, and most importantly, people.”

Mathematics also owes much to the preservation and innovation that came from the Muslim community, especially from the House of Wisdom founded in the 8th Century in Baghdad. Our current Hindu-Arabic number system was introduced to the West from this center. Ever tried to multiply or do long division using Roman numerals? Many new techniques in solving equations came from the mathematician al-Khwarizimi, whose Latinized name became the term for algorithm. The word “algebra” came from one of the words, “al-jabr,” in the title of his famous book on solving equations.

The House of Wisdom was also where many of the Greek classic texts had been translated into Arabic and preserved. The West would likely not have many of the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Euclid, had it not been for the preservation of these texts by this major contribution of Islamic civilization. Appreciating these contributions also helps us understand how much we owe to other religious traditions.

Eboo Patel also discusses the Jewish author Chaim Potok and his novel The Chosen . It is the story of two Brooklyn Orthodox Jewish boys, one whose father is a Hasidic rabbi; the other is more liberal and seeks to put his Jewish faith in conversation with the broader intellectual traditions of the modern world. While the fathers disagreed on many things, the more liberal father tells his son, “There is enough to dislike about Hasidism without exaggerating its faults.” It can be a very different position and we can disagree but “it ought to be appreciated as well.”

One of the challenges of interfaith dialogue is to learn how to disagree and yet have appreciative knowledge about other faith commitments. Interfaith is not a new belief system that says everyone is the same and we all essentially believe the same things. We have important differences, but we can still learn from each other and appreciate the values expressed through these different ways of understanding.

Patel is calling us to build bridges of cooperation across differences, and one of the important building blocks is this appreciative knowledge. Networks of engagement help create relationships among those who orient around religion differently. In this way, we build understanding that can lead to new friendships.

He describes hearing the former president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, speak. Mandela appreciated the role that many faith traditions contributed to his freedom. As he pointed in the direction of Robben Island, he said: “I would still be there, where I spent a quarter century of my life, if it were not for the Muslims and the Christians, the Hindus and the Jews, the African traditionalists and the secular humanists, coming together to defeat Apartheid.”

Yes, we are different and have different faith traditions, but we can differ and even disagree while at the same time appreciate others through our knowledge and through our friendships.

Posted on Permanent link for "Appreciative knowledge helps build bridges" by Doug Kindschi on August 10, 2021.

Permanent link for "Modern society and finding true happiness" by Doug Kindschi on August 3, 2021

“But are we happier?”

This is the question asked in one of the last chapters of the best-selling book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Author historian Yuval Noah Harari reviews in his not so “brief” story (over 400 pages) the development of early human forms, going back over 2 million years to the first homo sapiens some 200,000 years ago, and their eventual domination of the planet today. Harari, an Oxford Ph.D., organizes his sweeping story around three major revolutions: the cognitive, agricultural, and scientific revolutions.

Since the scientific revolution, he describes the result of the last 500 years as follows:

“The earth has been united into a single ecological and historical sphere. The economy has grown exponentially, and humankind today enjoys the kind of wealth that used to be the stuff of fairy tales. Science and the Industrial Revolution have given humankind superhuman powers and practically limitless energy. The social order has been completely transformed, as have politics, daily life, and human psychology.

“But are we happier?”

He suggests that most ideologies and political promises are “based on rather flimsy ideas concerning the real source of human happiness.” Historians research everything from politics and economics to diseases and sexuality, but rarely ask how any of this affects human happiness.

There have been impressive medical gains in terms of child mortality and extension of life span, as well as in the reduction of famines and poverty. Studies have shown, however, that “family and community have more impact on happiness than money and health.” Have our material advances combined with more mobility and individual independence been at the cost of community and family?

Only recently have scientists attempted to measure and study human happiness. Harari notes the most important finding is that “happiness does not really depend on objective conditions of either wealth, health, or even community. Rather, it depends on the correlation between objective conditions and subjective expectations.” He adds, “Prophets, poets, and philosophers realized thousands of years ago that being satisfied with what you already have is far more important than getting more of what you want. Still, it’s nice when modern research – bolstered by lots of numbers and charts – reaches the same conclusions the ancients did.”

Expectations are also important to our perceived happiness, but thanks to the media and advertising we are continually exposed to idealized images of what we should want and how we should look. We are even presented with both legal and illegal chemical means to improve happiness, but likely providing just temporary pleasure.

Nobel laureate in economics Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, points out a paradox in temporary experiences of pleasure or displeasure versus a long-term sense of happiness. For example, the day-to-day experiences of raising children provide many opportunities for drudgery or discouragement. From changing diapers and dealing with tantrums, to the many disappointments in the growing-up years, these are not particularly inspiring. But most parents will reflect back and affirm that their children are their greatest source of happiness. Again, the important distinction between pleasure and happiness points to what Harari concludes, “happiness consists in seeing one’s life in its entirety as meaningful and worthwhile.”

While historian Harari takes a secular and scientific perspective on these issues, he does point to the philosophers, prophets, and religious leaders who have taken a different approach to happiness. We know from other authors that happiness is a much different concept than individual pleasure. For example, Mahatma Gandhi taught, “Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” It has more to do with one’s integrity and consistency with how one feels. There is also the issue of whether we can even seek happiness as a goal, or is it something that comes to us when we are seeking and working toward something bigger than oneself? As Eleanor Roosevelt said, “Happiness is not a goal; it is a by-product.”

In American culture, happiness is often connected to individuality and autonomy. The Declaration of Independence declares “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as a basic right. While this American tradition and law promotes individual rights and happiness, most religious expressions describe happiness in terms of duty and responsibility. It’s not so much having our desires met and being successful and prosperous that brings happiness, but being true to one’s responsibility to God and to one’s authentic self.

Buddhism teaches the liberation from suffering by rising above the craving for particular feelings. The Psalms tell us to “worship the Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful song.” (Psalms 100:2) Considered one of the greatest thinkers in Islam, al-Ghazali wrote the book, The Alchemy of Happiness in which he taught that one achieves ultimate happiness by rejecting worldliness and finding complete devotion to God.

Christians often refer to the Sermon on the Mount, when the vision expressed in Jesus’ teaching of the Beatitudes offers the best way to happiness. Jesus calls “blessed” the merciful, the pure in heart, the peacemakers, etc. Some modern translations use the word “Happy” to describe these blessings. The 19th century Scottish publisher Robert Young translated the Bible seeking to be faithful to the literal meaning of the original words. His rendering of Jesus’ teaching recorded in Matthew was as follows:

“Happy those hungering and thirsting for righteousness -- because they shall be filled.

Happy the kind -- because they shall find kindness.

Happy the clean in heart -- because they shall see God.

Happy the peacemakers -- because they shall be called Sons of God.”

(Matthew 5:6-9, YTL – Young’s Literal Translation)

So, does our modern society with its prosperity, freedoms, and opportunity for pleasure and entertainment provide us with more happiness? Perhaps the answer is not from the historians, economists, or scientists. We must look deeper into the traditions from the poets, prophets, and priests in our search.

Posted on Permanent link for "Modern society and finding true happiness" by Doug Kindschi on August 3, 2021.

Permanent link for "Responding with courage and faith" by Doug Kindschi on July 27, 2021

Standing for what is right sometimes demands courage. Unfortunately, there have been times of hate speech and acts of hate in our world where our response may be put to the test.

Eboo Patel, the interfaith leader and founder of the Interfaith Youth Core, wrote about his fellow Chicagoan, Rami Nashashibi, whose deep Muslim faith inspires him to work for social justice in the poor neighborhoods of South Chicago. While with his three children in his neighborhood park, he realized that it was time for the scheduled prayer Muslims do five times a day. However, Patel wrote in the magazine Sojourners, it was just a few “days after the terrible terrorist attack in San Bernardino, where extremists calling themselves Muslims murdered 14 people and injured many more. … He found himself suddenly struck by fear at the thought of praying in public and therefore being openly identified as Muslim at a time when so many equated that term with terrorist.”

Patel goes on to relate an incident 50 years previously in that same Chicago park, when Martin Luther King Jr. was leading a march protesting housing discrimination. King was also fearful because of the racists who had threatened violence. He was actually hit in the head and knocked down by a brick that was thrown his way. Nashashibi was aware of that incident and, in fact, had been working to erect a statue of King in that very area.

In Patel’s words: “In that same place, 50 years apart, two men of different faiths faced a similar question: Would their faith be the victim of fear or the source of courage? Thousands of fellow protesters were watching King. Three Muslim children were watching Nashashibi.”

Despite his misgivings, he refused to teach his children fear. So he put his prayer rug down and began his prayers. In Nashashibi’s words, “I want them to understand that sometimes faith will be tested, and that we will be asked to show immense courage, like others have before us, to make our city, our country, and our world a better reflection of all our ideals.”

At one of the National Prayer Breakfasts, former President Obama spoke about the danger of fear. “Fear can lead us to lash out against those who are different, or can lead us to succumb to despair, or paralysis, or cynicism. Fear can feed our most selfish impulses, and erode the bonds of community. It is a primal emotion -- fear -- one that we all experience. And it can be contagious, spreading through societies, and through nations. And if we let it consume us, the consequences of that fear can be worse than any outward threat.”

Obama then spoke from his own Christian faith, quoting from II Timothy: “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love and of a sound mind” (1:7). Obama continued, “For me, and I know for so many of you, faith is the great cure for fear. … God gives us the courage to reach out to others across that divide, rather than push people away. He gives us the courage to go against the conventional wisdom and stand up for what’s right, even when it’s not popular.”

Sometimes courage is also required to stand up for someone else who is under threat. Obama went on to relate the story of the late Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds of the 422nd Infantry Regiment in the United States Armed Forces, who had been recognized by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. He is the first American soldier to be named as Righteous Among the Nations for rescuing Jewish servicemen at a POW Camp in Germany during World War II.

When Edmonds, the Christian prisoner, was ordered to identify which of the soldiers were Jewish, he ordered all of the troops to line up, all 1,000 of them. The Nazi colonel said, “I asked only for the Jewish POWs. These can’t all be Jewish.” Sgt. Edmonds stood there and said, “We are all Jews.” And the colonel took out his pistol and held it to the master sergeant’s head and said, “Tell me who the Jews are.” And he repeated, “We are all Jews.” Faced with the choice of shooting all 1,000 soldiers, the Nazis relented. Through his courage and faith, Sgt. Edmonds saved the lives of 200 of his Jewish fellow soldiers.

Should we ever be faced with fear as we seek to protect those we love, let our faith give us the courage to do what is right.

Posted on Permanent link for "Responding with courage and faith" by Doug Kindschi on July 27, 2021.

Permanent link for BELIEVING THAT, OR "BELIEVING IN," AS WE SEEK PEACE on July 20, 2021

“So, the people feared the Lord and believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses.” (Exodus 14:31)

This passage from the Exodus story was cited by a Jewish philosopher that I once heard speak. She went on to make the distinction between “believing that” and “believing in.” In citing the story from Exodus of the Israelites after being saved from pursuing Egyptian armies at the Red Sea, she commented that “belief in” God and in Moses is not merely belief that God and Moses exist, but reflects a trust in the persons, not just their existence.

Too often our philosophical and theological efforts are directed to questions of existence when we should instead concern ourselves with what and whom do we trust. The book of James in the Bible makes a similar distinction from a Christian perspective when we read, “You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe — and shudder.” (James 2:19) “Believing that” is of some interest, but the real question is in what or in whom does one trust? Where do I place my confidence? Or, if you will, how will I live my life; what values will I seek to follow?

Putting trust in a relationship is critical to life in general, not just to one’s theological commitments. One doesn’t just believe that a person exists, but believes in that person, has confidence and trust in that person. It is the basis of a marriage, or family, or any important relationship that one has.

This distinction applies not only to personal relationships but also to other commitments and beliefs that one engages. My work this past decade reflects my belief in interfaith understanding, not just that it exists. I trust that these efforts will contribute to better human relationships and peace. I am committed to working to know others better and to respect the way they see the world and their faith.

When the famous philosopher and mathematician Pascal died, his servant found a parchment stitched to the lining of Pascal’s coat. It recorded a profound religious experience that Pascal had years earlier and included the reference to the “God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and scholars.” Pascal was more interested in belief in God rather than merely the philosophical arguments for God’s existence.

As my interfaith work has progressed, I find this distinction more and more relevant to what I do. The philosophical arguments are of interest, but much more important for me has become what do I believe in. I believe that God can and does address humanity in various ways and traditions, but I have also come to believe in the person that my Christian tradition holds up as the one who most reflects God’s desire for what it means to be fully human.

It is not so much trying to speculate on “What Would Jesus Do? (remember that fad to wear the initials WWJD on a bracelet?) but seeking to follow Jesus in terms of what he did do. Call it WDJD – What Did Jesus Do?

As I read about Jesus’ encounter with the Canaanite woman who wanted her daughter healed, I look to see, what did Jesus do? She was not Jewish, she was a different race and belief, but Jesus did heal her daughter.

I read of the Centurion who was not only from a different nationality, but was part of the occupying forces. He asked Jesus to heal his servant. What did Jesus do? He healed the servant and praised him for his faith.

When Jesus met the Samaritan woman at the well, what did Jesus do? In the book of John, it says the Jews had no dealing with Samaritans, who were considered heretics. What did he do? He conversed, asked her for a drink, and respected her without judging her past.

And what did Jesus do, when the young lawyer asked him what he must do to inherit eternal life? If there is an ultimate religious question, it must be that.

Jesus told him to love God and love his neighbor.

When pressed by the lawyer regarding who is my neighbor, Jesus tells the story of a Samaritan, again someone from that rejected tribe.

In each case we don’t see Jesus discussing philosophy or theology. He doesn’t ask them to believe something abstract or agree to a creed. He expects them to believe in him and have confidence that he will act.

In our lives together in this increasingly diverse world, let us believe in each other and in the power of love to bring us to respect, acceptance and peace.

Posted on Permanent link for BELIEVING THAT, OR "BELIEVING IN," AS WE SEEK PEACE on July 20, 2021.

Permanent link for "PICKING FAVORITES FROM THE LAST SEVEN AND A HALF YEARS' BY DOUG KINDSCHI on July 13, 2021

In the past seven and a half years the Grand Rapids Press has published each Thursday in its Religion section the column Interfaith Insights. That represents nearly 400 columns plus other special articles and features to which we have contributed. Because of staff reductions and financial constraints at The Press, this week’s Insight will be the last one published in this format. We will, however, continue to write columns that you may read at the Kaufman Interfaith Institute website or delivered by mail.

For this last column in the Press, I’m sharing some of my favorite quotes from previous installments. I trust this will serve as a brief summary of those individuals and resources that have inspired my own insights these past years.

Jonathan Sacks: “Don’t think we can confine God into our categories. God is bigger than religion.”

Krister Stendahl: “In the eyes of God, we are all minorities. That’s a rude awakening for many Christians, who have never come to grips with the pluralism of the world.”

David Brooks: “To be religious, as I understand it, is to perceive reality through a sacred lens, to feel that there are spiritual realities in physical, imminent things.”

Elliot Cosgrove: “The great strength of a quest-driven faith is that it permits me to affirm my own beliefs, even as they develop, all the while respecting the integrity of another person’s path.”

Pope Francis “We do not have to make a distinction between believers and nonbelievers; let’s go to the root: humanity. Before God, we are all his children.”

Krister Stendahl: “Three rules for interfaith understanding:

1. When trying to understand another religion, you should ask the adherents of that religion and not its enemies.

2. Don’t compare your best to their worst.

3. Leave room for holy envy.”

Barbara Brown Taylor: “Could my faith be improved by the faith of others? … My envy of other traditions turned into holy envy, offering me the chance to be born again within my own tradition.”

Avishai Margalit: “Can Judaism, Christianity and Islam be pluralistic? The question is not whether they can tolerate one another, but whether they can accept the idea that the other religions have intrinsic value. … They will not only refrain from persecuting the others but will also encourage the flourishing of their way of life.”

Dick Rhem: “Good religion does not divide, but unites; good religion does not denigrate, but affirms; good religion enables us to transform all that would divide us.”

Eboo Patel: “It’s a potluck dinner versus the melting pot. The melting pot says we’re going to eliminate distinctiveness, but a potluck says we should bring something to the big, open table that welcomes different contributions from communities, and that’s the way the nation feasts.”

Amy-Jill Levine: “Conversations across religions need not, and should not, end with all the participants proclaiming an ultimate unity of belief. Such an exercise only waters down both traditions into a bland universalism that, in an attempt to be inoffensive, winds up offending everyone.”

Richard Mouw: “God is God, and we are not, which means that we fall far short of omniscience. … This means that what might at first glance appear to be our radical disagreement with a certain point of view might, upon humble reflection, require a confession of sin … It requires a spirit of theological humility.”

Nancy Fuchs Kreimer: “We are not God, so we don’t know how God most wants to be worshipped. We have a better idea how people want to be treated. We are not commanded to love our religions. We are commanded to love our neighbors.”

Billy Graham: (when asked whether he believes heaven will be closed to good Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus or secular people), “Those are decisions only the Lord will make. It would be foolish for me to speculate on who will be there and who won’t. ... I don’t want to speculate about all that. I believe the love of God is absolute. He said he gave his son for the whole world, and I think he loves everybody regardless of what label they have.”

Martin Luther King Jr.: “This is the great new problem of mankind. We have inherited a big house, a great ‘world house’ in which we have to live together – black and white, Easterners and Westerners, Gentiles and Jews, Catholics and Protestants, Muslim and Hindu, a family unduly separated in ideas, culture, and interests who, because we can never again live without each other, must learn, somehow, in this one big world, to live with each other.”

John Lewis: “In the final analysis, we are one people, one family, one house — not just the house of black and white, but … the house of America. We can move ahead, we can move forward, we can create a multiracial community, a truly democratic society. I think we’re on our way there. … We have to be hopeful. Never give up, never give in, keep moving on.”

Nelson Mandela: (pointing towards Robben Island, where he spent over 25 years in prison),/"I would still be there if it were not for the Christians, the Jews, the Hindus, the Muslims, the Baha'is, the Quakers, those from indigenous African religions and those of no religion at all, working together in the struggle against apartheid."

Donniel Hartman: “The human religious desire to live in relationship with God often distracts religious believers from their traditions’ core moral truths. Religious believers must hold their traditions accountable by the highest independent moral standards. Decency toward one’s neighbor must always take precedence over acts of religious devotion and ethical piety must trump ritual piety.”

Abraham Lincoln: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.”

John F. Kennedy: “This nation … will not be fully free until all its citizens are free. … While we rejoice over the liberation of the ancient Israelites, we remember that many others are still not free. … We give voice to those around the world and within our community who are excluded, oppressed, or enslaved. We are all part of one human family, all connected, and all responsible for one another.”

Abraham Joshua Heschel: “In a free society some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

Jonathan Sacks: “What will be the shape of a post-COVID-19 world? Will we use this unparalleled moment to reevaluate our priorities, or will we strive to get back as quickly as possible to business as usual? Will we have changed or merely endured? Will the pandemic turn out to have been a transformation of history or merely an interruption of it?”

Jim Wallis: “Hope is believing in spite of the evidence, and then watching the evidence change.”

Martin Luther King Jr.: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

I will continue my reading and sharing insights as we go forward and thank the readers who have joined us either through the Grand Rapids Press or from our weekly online Interfaith Inform newsletter. I trust you will continue.

Permanent link for "CAN WE EMERGE FROM THE PANDEMIC TO A "WE" CULTURE?" by Doug Kindschi on July 6, 2021

“What will be the shape of a post-Covid-19 world? That will be the defining question of the year ahead.”

This is the question Rabbi Jonathan Sacks asks in the Epilogue of his latest book, “Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times.” His questions continue: “Will we use this unparalleled moment to reevaluate our priorities, or will we strive to get back as quickly as possible to business as usual? Will we have changed or merely endured? Will the pandemic turn out to have been a transformation of history or merely an interruption of it?”

The book was released in the United States shortly before his untimely death in November of 2020. In the preface he wrote of his hope that “in the context of a post-pandemic world, the book might serve as a guide to how, after a long period of isolation, we might think about rebuilding our lives together, using the insights and energies this time has evoked.”

Morality and religion are closely connected in virtually every religious tradition, and for Sacks his Jewish faith is made clear as he summarized in the following paragraph:

“Love your neighbor. Love the stranger. Hear the cry of the otherwise unheard. Liberate the poor from their poverty. Care for the dignity of all. Let those who have more than they need share their blessing with those who have less. Feed the hungry, house the homeless, and heal the sick in body and mind. Fight injustice, whoever it is done by and whoever it is done against. And do these things because, being human, we are bound by a covenant of human solidarity, whatever our color or culture, class or creed.”

He notes that the coronavirus pandemic has challenged our exercise of self-restraint for the safety of others as our society has become more “I” centered. “We have had,” Sacks writes, “for some time now …too much pursuit of self, too little commitment to the common good.”

In recent times we have experienced polarization in our communities and unfortunately religion has been a component. Islamophobia and anti-Semitism incidents have increased. Christian communities have been divided over social and political issues. As we come out of extended isolation during the COVID shutdown and restrictions have been relaxed, let us also seek to renew personal relationships in ways that open us up to better understanding of each other. Following our time of coming together physically for the July Fourth celebrations, let us also come together across religious and political divisions for a renewed understanding of our shared humanity.

In the closing epilogue of the book, Rabbi Sacks sets forth five aspects of his hope “that we emerge from this long dark night with an enhanced sense of ‘We.’”

Rarely has all of humanity faced the same challenges, dangers, and fears at the same time, and Sacks writes, “I hope we will see a stronger sense of human solidarity.”

A tiny virus has threatened the whole of humanity despite our affluence and power, so “I hope we will have a keener sense of human vulnerability.”

Noting that countries with high-trust cultures and faith in government to be honest fared best in their response, Sacks says, “I hope we strengthen our sense of social responsibility.”

Responding to the many who during lockdown and isolation reached out to others in need, Sacks continues, “I hope that we will retain the spirit of kindness and neighborliness.”

Finally, “I hope we will emerge from this time of distance and isolation with an enhanced sense of what most we have missed — the ‘We’ that happens whenever two or more people come together face-to-face and soul touches soul.”

Let us not let this crisis go to waste, but let it be the opportunity to recover a basic morality that has been taught throughout our religious history and is needed again at this time.

Permanent link for "OUR NATION FACING A CHOICE BY HEEDING THE PROPHETS" BY DOUG KINDSCHI on June 29, 2021

As we look to another Fourth of July, do we celebrate the 245th

anniversary of our country’s independence or should we worry about our

country’s future? Our polarization has led to multiple expressions of

concern about our ability to survive and thrive as a nation. Can we

come together or are we on a track to decline? A few years before his

death, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks addressed the question of “Why

Civilizations Fail,” and began by quoting Moses:

"Be careful that you do not forget the Lord your God. …

Otherwise, when you eat and are satisfied, when you build fine houses

and settle down, and when your herds and flocks grow large and your

silver and gold increase and all you have is multiplied, then your

heart will become proud and you will forget the Lord your God, who

brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. … You may say to

yourself, ‘My power and the strength of my hands have produced this

wealth for me.’… If you ever forget the Lord your God … I testify

against you today that you will surely be destroyed.” (Deut. 8:11-19)

Reflecting on this passage, Sacks continued with the warning that

it is not the suffering in the wilderness that is the real test. The

real challenge will begin “precisely when all your physical needs are

met – when you have land and sovereignty and rich harvests and safe

homes – that your spiritual trial will commence.”

This is seen as an early version of what many historians have

observed over the centuries as they look at the history of

civilizations. Sacks points to the 14th century Islamic thinker, Ibn

Khaldun, who in his introduction to history was one of the first to

observe that great civilizations become too comfortable and

complacent, leading to a period of decay and eventual decline.

In his “History of Western Philosophy,” Bertrand Russell notes a

similar pattern in what he considered to be examples of great

civilizations. In his introduction he notes: “What had happened in

the great age of Greece happened again in Renaissance Italy:

traditional moral restraints disappeared … the decay of morals made

Italians collectively impotent, and they fell, like the Greeks, under

the domination of nations less civilized than themselves but not so

destitute of social cohesion.”

British historian of the last century, Arnold Toynbee, studied 26

different civilizations in his 12-volume “A Study of History.” I

don’t claim to have read this major work, but according to Britannica

on the web, he concluded: “Civilizations declined when their leaders

stopped responding creatively, and the civilizations then sank owing

to the sins of nationalism, militarism, and the tyranny of a despotic

minority.” The Britannica also noted that Toynbee “saw history as

shaped by spiritual, not economic forces.”

Sacks summarized this spiritual decline thus: “Inequalities will

grow. The rich will become self-indulgent. The poor will feel

excluded. There will be social divisions, resentments and injustices.

Society will no longer cohere. People will not feel bound to one

another by a bond of collective responsibility. Individualism will

prevail. Trust will decline. Social capital will wane.” Is this our

situation today?

Sacks suggests that this decline is not inevitable and proposes

three rules to guard against it.

Rule 1: Never forget where you came from.

He admonishes us to

focus on justice, caring for the poor, ensuring dignity for everyone

and “making sure there are always prophets to remind the people of

their destiny and expose the corruptions of power.”

Rule 2: Never drift from your foundational principles and

ideals.

Sacks explained, “Societies start growing old when they

lose faith in the transcendent. They then lose faith in an objective

moral order and end by losing faith in themselves.”

Rule 3: A society is as strong as its faith.

This faith is

necessary in order “to honor the needs of others as well as ourselves

… (and) give us the humility that alone has the power to defeat the

arrogance of success and self-belief.”

Given this warning from Rabbi Sacks, I have recently reflected on

the current book “The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago

and How We can Do It Again,” by Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Garrett.

They point to an earlier time at the beginning of the 20th century

when as a nation we experienced great selfishness, division, and

income disparity. In their sociological research they point to the

“upswing” that happened in that century, when the disparities and

polarization of the early 1900s gave way to increased collaboration

and care for the larger good. This led to a more egalitarian and

cooperative society that peaked in the mid-century during the

Eisenhower presidency.

This upswing was marked by desegregation of the armed forces,

expanded Social Security coverage, more public housing, and better

health care and education. There was also cooperation on a massive

investment in infrastructure, notably the interstate highway system.

Putnam and Garrett also document the “downswing” during the second

half of the century leading to the current polarization and inequities

that are similar to the early part of the 1900s. But they do not give

up hope but instead analyze how the last century’s upswing developed

-- and why it can happen again.

So where are we this Fourth of July? Have we already gone too

far down this path of spiritual decline? Have we lost our social

cohesion? Do we honor the needs of others, especially the poor? Have

we lost faith in a moral order? Is it too late to regain a collective

responsibility? Rabbi Sacks also makes the distinction between

prediction and prophesy. Prophets do not predict -- they warn. “If a

prediction comes true it has succeeded; if a prophecy comes true it

has failed. The prophet tells of the future that will happen if we do

not heed the danger and mend our ways.”

Can we heed the current prophets like Sacks and look to an

upswing that will bring a renewed commitment to the common good? Let

us also heed the ancient Hebrew prophet’s call “to do justice, love

kindness, and walk humbly with our God.” (Micah 6:8)

Permanent link for "Seeking the common good through personal relationships" by Doug Kindschi on June 22, 2021

How do we encounter the increasing polarization in society and in ourselves?

Rabbi Jack Moline is the president of the Interfaith Alliance and

Rabbi Emeritus of Agudas Achim Congregation in Alexandria, Virginia,

where he served for 27 years. I heard him speak at a workshop

sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations on religion and foreign

policy. As a conservative rabbi he has become a national powerful

voice for religious freedom for all, regardless of faith or beliefs.

The Jewish rabbinic tradition holds that humans have two inclinations,

one to good and the other to evil. But noting that evil cannot be

redeemed but only destroyed, Moline proposed instead the contrast

between altruism and selfishness. Selfishness, he asserted, can be

changed and redeemed.

The key is the affirmation of love, which is taught by all of

the religious traditions. The first step is the act of invitation:

inviting into conversation the person who may seem to be the stranger

or the person with whom you totally disagree. It is by conversation

that we can move toward seeking the common good. As long as we stay in

our isolated echo chambers and fail to reach out to someone who

believes differently, either in terms of religion or in politics, we

will never move to the common good. It is in brave acts of conscience

that we can find the common ground that will enable us to change

attitudes, values, and even laws.

These brave acts are not likely to come from our politicians who

are reluctant to make bold statements that could alienate their base.

The point was made that politics is “downstream from culture.” Or as

one of the panelists put it, “Politicians look for a parade and then

try to get in front of it.” There are notable exceptions but in

general this is a reliable maxim.

Significant change toward the common good must come from our

basic values, and it is the religions that perpetuate and form our

values. In my years of interfaith work I have been privileged to not

only learn about the many differences between the religious stories

and differing truth claims, but to also learn about the essential

agreement on basic values. I have especially learned this by

developing personal relationships with people from very different

cultures and religious perspectives. We don’t have to agree on

everything in order to learn from each other. In fact, it can be

argued that we will never learn if we only interact with people with

whom we agree. That will only solidify our attitudes and prejudices.

Without personal relationships, all you have are categories.

When I put someone in a category I learn nothing, but merely reinforce

a limited and probably inaccurate stereotype. It is such stereotypes

that then lead to discrimination and prejudice. It is when we

encounter people in a personal relationship that we open ourselves to

being informed and even change. Of course in the process the other

person is also opening to change. In such encounters we have the

opportunity to find ways to promote the common good.

Whether it is an inclination to good vs. evil or altruism vs.

selfishness, we can make the decision to be open to new ideas, new

experiences, and new encounters with those we might be tempted to see

as “other” or as just a category.

The easy route is to just stay in our own ways and not take up

the challenge. But each decision we make is taking us down the road

to a more isolated and ultimately selfish perspective -- or to a

larger world of ideas and the potential to achieve the common good.

I am reminded of a story often attributed to the Cherokee

people. An old chief was teaching his grandson about life. He told

the boy that we are all born with two wolves within us, and there is a

terrible fight going on between these two wolves. One wolf is evil,

prone to anger, envy, greed, and selfishness. The other is good and

seeks peace, love, kindness, generosity, compassion, humility, and faith.

The chief tells his grandson that the same fight is going on

inside you and every person. After thinking about it for a while the

grandson finally asks his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?”

To which the old chief simply replied, "The one you feed."

Whether it is the rabbinic scholars or the Native American chief,

we must face the choice we all have as we go through life. Are we

feeding the inclination to do good, encountering the other, and

seeking peace? Let’s make this our commitment in the days ahead; our

choice will either bring more polarization or move us toward the

common good. Let us feed the good inclination as we encounter those

not like us.

Permanent link for "In a climate of fear and hate, can we learn from a six-year-old?" by Doug Kindschi on June 15, 2021

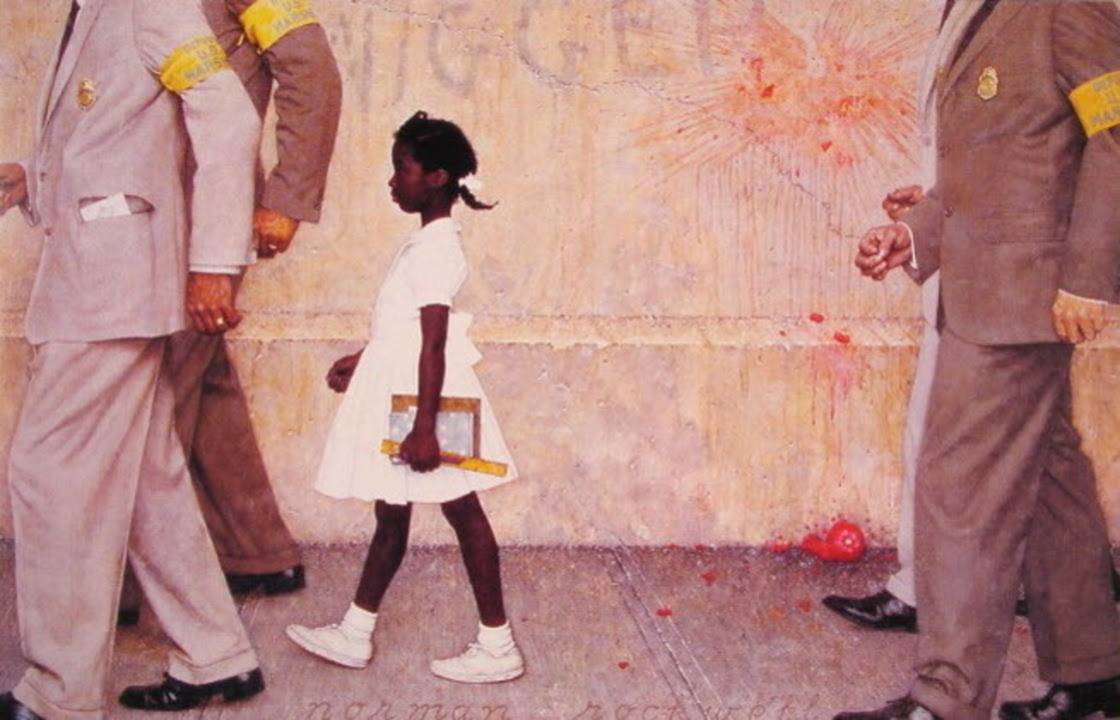

How can we deal with the division and even hatred we observe in our society? Recalling an earlier time, when our society was divided to the point of hate, can be instructive. In this case the teacher is the 6-year-old Ruby Bridges, who in 1960 was escorted by federal marshals to a white elementary school in New Orleans. As the only black student in the all-white school, she studied alone that year with Barbara Henry, a young teacher from Boston, and the two worked together in an otherwise vacant classroom for an entire year. Every day the marshals escorted Ruby Bridges to school, and she remained in the school even when all of the other parents withdrew their children.

Her case became known nationally in news reports and later when the artist Norman Rockwell painted the event of her attending school with federal marshal escort. The painting, titled “The Problem We All Live With,” was featured in Look magazine in 1964 and became an iconic representation of school integration efforts of that decade.

The protests against school integration aimed at this young child as she went to school each day were truly disturbing, as hundreds shouted their threats and hatred. The child psychiatrist Robert Coles took an interest in Ruby Bridges and wondered how she could stand up to all of this pressure. He began meeting with her weekly to learn more about how she was dealing with it all.

One day her teacher mentioned that she saw Ruby talking to the protesters outside the school building. When Coles asked Ruby what she was telling them, she responded that she wasn’t talking to them; she was talking to God and praying for the people in the streets.

In an interview, Coles asked her why she was praying for the people in the streets. She looked at him and said, “Don’t you think they need praying for?” When asked where she got that idea, she responded that she got it from her mother and father and from their minister in church. She said she prayed for them every morning on the way to school and also on the way home. Coles then asked what she prays, and she responded that she always said the same thing: “Please, dear God, forgive them because they don’t know what they are doing.”

This very young child had learned from her parents, who themselves could not read or write, this truth which Jesus had said from the cross and the Hebrew prophets had declared repeatedly. Forgiveness is also central in the Quran and taught by all of the religions. It is the key not only to peace among people but also to living with oneself without resentment and self-hate.

Robert Coles went on to teach at Harvard University’s School of Medicine and to write the Pulitzer Prize-winning series “Children of Crisis,” as well as books on the moral and spiritual intelligence of children. In addition to his over 80 scholarly books, he also wrote the illustrated children’s book, “The Story of Ruby Bridges.” In that same interview, Coles exhorts us to not just strive to get an A in biblical literature, or an A in moral analysis, but to “get the kind of ‘A’ Ruby got” by living out this attitude toward others.

Have things changed since that year in the 1960s when Ruby was the only student who attended her school for the whole year? Yes, as the year progressed, Ruby continued to study alone with that teacher and eventually the crowds protesting outside began to thin. The following year the school enrolled additional Black students, and Ruby eventually graduated from a desegregated high school. Ruby later married and raised four sons.

In the 1990s she reunited with her first teacher and the two did speaking events together. Ruby later wrote two books about her early experiences and received the Carter G. Woodson Book Award. She continued her activism for racial equality and established the Ruby Bridges Foundation to promote tolerance and change in education.

Yes, we have made changes impacting many individual minority students, but there is still much to do. Systems of racial disparity permeate our education, culture, and economic structures. In our current political environment, when disagreement, misunderstanding and conflict often turn ugly to the point of hate talk and hate action, we need to learn again the simple truth that was expressed by this 6-year-old. As we examine our own attitudes toward those with whom we disagree, whether it is political or religious, we may need Ruby’s forgiveness prayer for ourselves.

In an issue of the magazine Christian Century, publisher Peter Marty reminded us of this story and wrote, “We ought to pray those Jesus words ourselves, speaking them with the confident spirit of Ruby Bridges: ‘Please dear God, forgive us because we often don’t know what we’re doing.’”

Permanent link for "Coming from the earth: humus, humanity, and humility" by Doug Kindschi on June 8, 2021

It is gardening season again and as we till the earth we are also

reminded that the whole Earth is our home. We have a responsibility to

live in our homes in relationship and reciprocity. We wouldn’t trash

our personal home and must live in our common home with the same kind

of respect. I would like to pursue this further into the actual dirt,

or earth, that is the base for gardens, as well as the source for what

it means to be human.

We know this image well. We are created from the dust of the

earth according to Genesis. And the first man is named Adam from the

Hebrew word adamah, meaning earth or ground. At funerals, the

committal rite often includes the phrase from the English Book of

Common Prayer, “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

The word human comes from the Latin word humus, meaning earth or

ground. In a meditation the Franciscan priest and author Richard Rohr

wrote: “Being human means acknowledging that we’re made from the earth

and will return to the earth. We are earth that has come to

consciousness. … And then we return to where we started — in the heart

of God. Everything in between is a school of love.”

Humus is also a gardening term that refers to the components of

soil that are rich in organic matter. It is the final result of

mixing yard material like leaves with leftover plant food products and

leaving them to decompose into what is called compost. It is the

recycling of plant material. Think of it as “earth to earth” for the

plant world.

Author and educator Parker Palmer also uses these images in an

essay titled “Autumn: A Season of Paradox”: “I find nature a

trustworthy guide … As I’ve come to understand that life ‘composts’

and ‘seeds’ us as autumn does the earth, I’ve seen how possibility

gets planted in us even in the most difficult of times.”

Philosopher Brian Austin, in his book “The End of Certainty and

the Beginning of Faith,” tells of hiking with his family along the

trails which parallel stream beds in the Great Smoky Mountains. They

often return with mud-caked hiking boots. While he finds himself

impressed with the majesty of the mountains, it is also (in his words)

“the mud, still glistening with the mist that makes dust come to life

[that] harbors mysteries as magnificent as the mountains …”

“From that mud, from its carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, and

assorted metals, a child can be woven. The atoms in that mud, the same

kinds of atoms that comprise my children and you and me, have existed

for billions of years. ... This mud is spectacular, and we believe

that God made it so. This mud is rich, pregnant with possibility. …

To see ourselves as made of the same stuff that rests under our boots

as we journey a mountain path is no insult to human dignity, no

affront to the image of God in us; it is rather a reminder of the

majesty of inspired mud, a reflected majesty that gives us but one

more fleeting glimpse of the blinding brilliance of the maker of the mud.”

These authors remind us that in the cycle of life we are closely

related to the earth. We have much in common with compost and mud,

which contain the chemicals that also make up our bodies. They affirm

that we are God-breathed dust, made from the humus. We are mud balls

who have been created in the image of God.

Another word that comes from the Latin root humus is humility. We

see it expressed by Abraham when he bargains with God to spare the

righteous people in Sodom. In Genesis 18 he expresses it thus: “Now

that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, though I am nothing

but dust and ashes.” Likewise, Job in his lamentation refers to God

as the one who “throws me into the mud and I am reduced to dust and

ashes.” (Job 30:19)

Eugene Peterson put it this way: “The Latin word humus,

soil/earth, and homo, human being, have a common derivation, from

which we also get our word 'humble.' This is the Genesis origin of who

we are: dust -- dust that the Lord God used to make us a human being.

If we cultivate a lively sense of our origin and nurture a sense of

continuity with it, who knows, we may also acquire humility.”

Fully understanding who we are requires the realization that we

are indeed part of the earth, the soil, the humus, to which we will

return. It is only by God’s grace that we have life. The confidence

and faith that we have is important to affirm, but we must also be

humble in recognizing that there is so much more that we do not

understand or possess.

As we plant and tend to our gardens this spring and early summer,

let it be a reminder that the whole Earth is a garden and our bodies

are made of the same dirt and humus that sustains the plants. Let us

also be reminded that every person in our community, be they refugees

or immigrants, people who are different in race or class or political

persuasion, or persons of a different faith or of no faith, have all

come from this same soil. The humus that comprises our bodies also

calls us to humility as we interact with all people comprised of the

same earth components. We are called to recognize our common humanity

with humility.