Interfaith Insight - 2020

Permanent link for "Monuments tell stories, sometimes false ones" by Doug Kindschi on August 11, 2020

In the past two weeks’ Insights I have written about statues and

monuments, with particular attention to monuments that become symbols

that verge on the sacred and run the danger of becoming idols. Statues

and monuments tell stories, sometimes to inform about our history in

ways that can be educational, but sometimes to tell a different

political story that seeks to create a new history that is false.

As I have become more aware of the statues in Grand Rapids, I

have found both kinds. For example, I was not previously aware of the

story of three scientists from Grand Rapids who made the critical

discoveries leading to the vaccine against whooping cough. In the

1930s, bacteriologists Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering, working in

Grand Rapids with Michigan Department of Health laboratories, began

collecting samples from children who were suffering from whooping

cough, one of the deadliest childhood diseases of that time. Their

research led to the development and field testing on one of the first

effective vaccines to prevent the disease. In the 1940s an African

American scientist named Loney Clinton Gordon joined the lab. She

isolated a new strain of pertussis that led to a more effective

vaccine. The work of these three women supported research on the DTP

shot that protects against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis or

whooping cough. This standard vaccine is used today enabling parents

to safely vaccinate their children against multiple diseases at once.

The work of these scientists in Grand Rapids in the middle of the

Depression resulted in tens of thousands of children being saved from

death by this terrible disease. Their story is introduced by a statue

at Michigan State University’s new research center for the College of

Human Medicine on the corner of Michigan Street and Monroe Avenue. Of

course a statue is only the beginning of the story of these three

women and the larger efforts of many others working in the state

laboratory in Grand Rapids. It did, however, lead me to learn more

about them and their inspiring story, including a report on the

History.com website that can be accessed at: www.bit.ly/GRscientists.

One also learns more from this report that Grand Valley State

University history professor Carolyn Shapiro-Shapin researched this

aspect of health and vaccine history and has written several scholarly

articles on it. The statue can’t tell the whole story, but it

introduces us to an important aspect of our city’s history and the

inspiring story of a disease conquered.

A half-block away on Monroe Avenue NW is a statue of Lyman Parks,

Grand Rapids’ first African American mayor. He served from 1971 to

1976 and is recognized for his important role in initiating the

revitalization of downtown Grand Rapids.

These stories are worth remembering as we seek to understand our community.

But there are other statues and monuments in our country and even

in our community that tell or seek to reinforce false narratives. The

statue of Noahquageshik, also referred to as Chief Noonday, located on

the riverbank near the Blue Bridge, has been described as portraying

him welcoming the settlers, while ignoring the suffering and genocide

of Native Americans by European settlers. I have benefited from

feedback from Native Americans who want the fuller story told.

The Civil War statue in Allendale’s Veterans Garden of Honor has

been controversial and properly protested against. Why a community in

Michigan, whose Civil War units sent 90,000 soldiers from our state to

fight for the Union, would depict a rebel Confederate soldier with

equal standing to the Union soldier is beyond my understanding. The

depiction of a diminished black slave at their feet reaching for

freedom is despicable and should also be protested. Why not portray

one of the 1,600 Black soldiers who also served with the 1st Michigan Infantry?

I have written in previous Insights about the idolizing of

Confederate statues that are also in the news, but now the question is

what should be our action. Instructive commentary, consistent with my

intent can be found in the current issue of Christian Century. Peter

Marty, the editor/publisher, writes an essay titled, “Sanitizing

history.” He decries “the fictional narrative behind the (Confederate)

monuments themselves … installed to rewrite history and whitewash

truths about the searing legacy of slavery.” He notes that “these

towering monuments served to disguise the Confederacy’s doomed act of

mass treason and failed attempt to preserve slavery.”

Marty continues to call for further attention to the issue of

removal of such monuments and quotes the former mayor of New Orleans,

Mitchell Landrieu, who led the process of the city taking down four

Confederate monuments, including a 60-foot one honoring Robert E. Lee.

He quotes Landrieu: “Consider these monuments from the perspective of

an African American mother or father trying to explain to their

fifth-grade daughter who Robert E. Lee is and why he stands atop our

beautiful city. Can you do it? Can you look into that young girl’s

eyes and convince her that Robert E. Lee is there to encourage her? Do

you think she will feel inspired and hopeful by that story?”

In a recent video interview, Landrieu explained that while it is

important to remove a memorial that depicts a false narrative, the

process of making that decision is also important. His efforts in New

Orleans took over three years and were difficult and laborious, but

that was also part of the community’s education about the sanitizing

of our history. However, when the authorities refuse to do this, then

protests are not only appropriate but patriotic and become the

beginning of that educational process.

I agree with all of these sentiments and it is what led me to

conclude in my July 30 column, “Remembering our history is important,

but we must be mindful that statues that become monuments can also

become symbols that verge on the sacred and run the danger of leading

to idolatry. Our faith traditions as well as our good sense should

warn us against such misuse.”

Statues and monuments tell stories and they should seek to be

honest in what they portray. They can never tell the whole story and

it is important to correct the errors or misguided impressions that

may have motivated such stories. This can be a process of education

and learning for our communities as we go through the often painful

process of correcting our history.

Permanent link for "History, statues, monuments, and idols: a long history" by Doug Kindschi on July 28, 2020

The current discussion about the removal or destruction of monuments remains in the news. This is not a new issue in American history, or even in world religious history. In 1776 following a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, a mob pulled down the equestrian statue of King George III. The metal was melted and used to make bullets for the Revolutionary War effort.

It is not necessary to preserve that statue of King George for us to remember the Declaration of Independence or the American Revolution that followed. The tearing down of the statue is also history. Please don’t get me wrong. I’m not advocating mob actions of tearing down statues, nor am I in favor of another violent revolution. But I do believe we need to think clearly about the proper role of statues and monuments in the telling of our history.

One of the earliest pre-revolution Anglican churches was King’s Chapel in Boston. Even though its members and clergy pledged their allegiance to the King of England, it is not necessary to tear down the church; but neither is it necessary to erect a monument to the king in order for that bit of history to be remembered.

But I do believe the status of honored memorials needs re-evaluation given current issues in our society. That said, we have forums and settings where that can be debated and decisions made on what is in the best interest for our society and for proper remembrance of our history.

Thomas S. Kidd, the Vardaman Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University, discussed this in a recent article in the magazine Christianity Today. He notes monuments were created at a particular time and for a certain purpose. The university in which he teaches was named for Judge R. E. B. Baylor, a Baptist leader, Southern politician, and a slave holder. The university has appointed a commission to discuss and recommend on how that history is to be remembered, including the future of a statue on campus honoring founder Judge Baylor.

His article also discussed a 7-foot monument in Selma, Alabama, not erected until 2000 to honor a Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest. While supposing to honor a general for his war efforts, the inscription does not mention that he was also responsible for the massacre of African American troops in Tennessee, and later was a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. The inscription reads, "This monument stands as a testament of our perpetual devotion and respect for Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest CSA 1821-1877, one of the South's finest heroes." It is not hard to imagine the message sent to the Black community living in proximity to the monument. I doubt that it enhances their historical understanding.

Professor Kidd concludes, “Removing monuments to figures such as Forrest should be an easy call for Americans, especially for Christians. … He committed racial atrocities in the name of a rebellion against the United States. If standing on public land, such monuments should be removed and at most be displayed in a museum, not in a place of honor.”

It gets more complicated when it is a confederate general who didn’t own slaves, or a founding father who played a major role in the creation of our nation but did own slaves. Kidd continues, “Deciding not to give someone a place of symbolic honor is hardly the same thing as erasing history. If all you know about Lincoln comes from viewing a statue of him, you don’t know much about Lincoln anyway. Libraries hold thousands of books on Washington, Lincoln, and even figures such as Nathan Bedford Forrest, and that should not change. What we’re talking about with monuments is publicly celebrating historical figures.”

The 20th century theologian Paul Tillich made the distinction between signs and symbols. Signs, he said, are arbitrary and provide information like a street or stop sign, or a sign identifying a business or historical place of interest. For Tillich, symbols participate in what it is that they signify, like a flag, the cross for Christians, or the Star of David for Jews. While seeking to point to that which is sacred, they can become almost sacred in themselves. It is idolatry when the symbol itself becomes worshiped, rather than just pointing to or symbolizing the sacred.

In our current discussions, I wonder if the monuments under consideration have gone beyond providing historical information, but have become objects representing a reality that has been lost, a memory that verges on worship of a bygone era. Why would there be over 1,700 confederate monuments put up some 50 years after the end of the Confederacy? Was it to provide historical information or was it to symbolize a mindset of what the Confederacy represented, including slavery? Was it seeking to keep alive an idea that refused to be totally defeated? And when do such monuments and other symbols like flags take on a symbolic meaning that tries to create a reality that becomes almost sacred?

The religious traditions on this matter are also instructive. The Hebrew Scriptures set forth the Ten Commandments in both Exodus and repeated in Deuteronomy, including the prohibition: “You shall not make for yourself a carved image.” (Exodus 20:4) The warning against idols appears over 100 times in the Christian Scriptures which of course include the Torah, Psalms, and prophets.

Islam also has strong injunctions against idolatry, traditionally prohibiting any picture or sculpture depicting the prophet Mohammad or any living person or animal.

Remembering our history is important, but we must be mindful that statues that become monuments can also become symbols that verge on the sacred and run the danger of leading to idolatry. Our faith traditions as well as our good sense should warn us against such misuse.

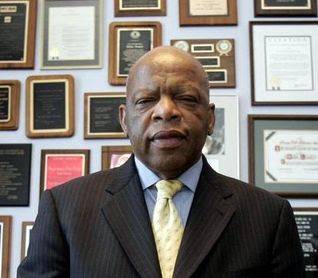

Permanent link for "John Lewis joined other religious leaders in the call for justice" on July 21, 2020

In the midst of so much negative news, the sad news of the death of

John Lewis does remind us of this very positive and effective voice

for social and racial justice. It also takes us back to that tragic

event some 55 years ago when Lewis nearly lost his life on the Edmund

Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Reflecting on it years later, Lewis,

a young age 25 at the time, said, “At the moment when I was hit on the

bridge and began to fall, I really thought it was my last protest, my

last march. I thought I saw death, and I thought, ‘It’s okay, it’s all

right. … I am doing what I am supposed to do.’”

Years earlier he had met Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther

King, Jr. who had inspired him “to get into good trouble and I’ve been

getting into good trouble ever since.” He was the youngest of the

close circle around M.L. King, Jr., first as a founder and president

of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and then as a

member of the House of Representatives for over three decades. He

became the nation’s conscience on matters of justice and a powerful

voice in Congress.

Lewis was motivated by his deep Christian belief and considered

the civil rights movement a religious phenomenon. Last week just

hours before Lewis’ death, another civil rights leader and close

associate with King also died. Rev. C. T. Vivian was considered the

“resident theologian” in King’s inner circle because of his deep

understanding of the connections between the Bible and the political

struggle in which they were engaged. He was 15 years older than Lewis

and died at the age of 95.

The Washington Post story on Rev. Vivian tells of his encounter

with the authorities one month prior to the “Bloody Sunday” on the

Edmund Pettus Bridge. Hundreds of black Americans had been stopped

from trying to register to vote. Vivian confronted the local sheriff

who had been blocking the effort, wagging his finger into his face and

saying “You can turn your back now and you can keep your club in your

hand, but you cannot beat down justice. And we will register to vote,

because as citizens of these United States, we have the right to do

it.” Whereupon in front of the cameras, the sheriff punched Vivian in

the face.

Other religious leaders became involved in the 1965 events in

Selma, including Rabbi Abraham Heschel who had met King and others at

a conference in Chicago. Heschel gave a talk titled “Religion and

Race.” His talk sought an expansive understanding of God’s work in

the world and called for the kinship with all people regardless of

race or religion, pointing specifically to “a deadly poison that

inflames the eye, making us see the generality of race but not the

uniqueness of the human face. … The Negro is a stranger to many souls.

There are people in our country whose moral sensitivity suffers a

blackout when confronted with the black man’s predicament.”

He continued pointing to the connection between the crime of

murder, which is punishable by law, and the sin of humiliation which

is invisible, saying, “When blood is shed, human eyes see red; when a

heart is crushed, it is only God who shares the pain.” Heschel

concluded his talk with the quote from the Hebrew prophet Amos, later

made famous in talks by King: “Let justice roll down like waters, and

righteousness like a mighty stream.” (Amos 5:24)

Two years later Heschel marched with King in Selma and later

recalled that it felt like his “legs were praying.” For both leaders

it was a religious responsibility to be concerned for all suffering

human beings since they were all created in God’s image. King

considered Heschel a modern-day prophet.

In Jon Meacham’s book, “The Soul of America: The Battle for Our

Better Angels,” he writes about John Lewis based on an extensive

interview he had with him in 2015, the 50th anniversary of the Selma

march. Lewis was born to sharecropper parents and dealt with a

childhood stutter “by preaching to the chickens on the family farm.”

Lewis had expected to be arrested in the march and had even included

in his backpack some fruit, toothbrush, and some reading material for

his use in jail. He had not expected a crushing blow to his head

causing fracture, but he was prepared to die.

Lewis considered the civil rights struggle a battle of whether

the best of the American soul could win over the worst of hatred and

fear. Meacham quotes Lewis:

“(W)e must humanize our social and political and economic

structure. When people saw what happened on the bridge, there was a

sense of revulsion all over America. … In the final analysis, we are

one people, one family, one house — not just the house of black and

white, but … the house of America. We can move ahead, we can move

forward, we can create a multiracial community, a truly democratic

society. I think we’re on our way there. … We have to be hopeful.

Never give up, never give in, keep moving on.”

Meacham’s newest book, “His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and

the Power of Hope,” is a biography of Lewis and will be released next

month. In interviews reflecting on Lewis’ death, Meacham says, “if we

only acted on what so many Christians say they believe, but so rarely

actually put into action, we could in fact create that world where

justice comes down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

For him it wasn’t rhetoric, it wasn’t a sermon, it was reality.”

Meacham goes on to say that Lewis “was on that bridge, he was in

those buses, in that House chamber, because of the gospel. He never

wavered from that faith.” Meacham continues, “There are so many

people who look a lot like me, who say they are religious, who say

they follow the Lord … and yet manage to overlook the Sermon on the

Mount, because folks are more worried about the Supreme Court.” Lewis

believed in the very end that “there is a power to a religious vision

of the world that can open our hearts rather than leading us to clench

our fists.”

Can we each catch this vision from John Lewis and

other religious leaders? Can we never give up, never give in? Can we

catch the vision from the Sermon on the Mount and from the Hebrew

prophets as we follow our faith in seeking that better community for

all people, for all races, and for all faiths?

Permanent link for "An approach to Israel-Palestine understanding" by Doug Kindschi on July 14, 2020

Last week a great friend of the interfaith institute and of Grand

Valley State University died at age 99. Seymour Padnos and his wife,

Esther, had been generous to the university and to the institute, and

became personal friends as well. During my 28 years as a dean, I had

many opportunities to engage with them regarding the new science

building which bears their names, as well as the Padnos College of

Engineering and Computing. I always knew of Seymour’s deep

Jewish faith, and then as the founding director for the

Kaufman Interfaith Institute I became more aware of his commitment

to interfaith understanding as well. He supported Sylvia Kaufman’s

early efforts in the 1980s to establish a Jewish-Christian dialogue in

Muskegon, and continued both in attendance and support as the

institute took shape this past decade.

Seymour was always kind, gentle, and more interested in what I

was doing than in talking about himself. But as I got to know him

better I learned of his bringing the professor of Old Testament from

the University of Chicago Divinity School to lecture at Hope College

on Jewish-Christian relations. It was the same professor with whom I

had studied back in the 1960s and who arranged for my wife and me to

be invited to a Jewish home in south Chicago to celebrate Passover.

It was my first significant interfaith experience and had a profound

impact that has influenced me to this day. I will always be grateful

to that professor and to Seymour Padnos for the many ways they both

enriched my life and understanding.

Another Jewish figure who has recently been important to my

understanding is the senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in

Jerusalem, Yossi Klein Halevi. Emigrating from Brooklyn to Jerusalem

in 1983 at age 27, he is a reporter, columnist, and author of a number

of books reflecting his own journey of understanding. His father was a

Holocaust survivor who was very instrumental in his own early

development as he responded with anger about what had happened to the

Jews. But then he realized that he was living in what was perhaps the

most fortunate generation for Jews in all of history. He was not in

physical danger, enjoyed freedom living in America, and Jews had

returned to their homeland and established a state. It was the exact

opposite of his father, who probably lived in what was the least

fortunate generation to be Jewish with the systematic killing of

millions of his people during the Holocaust. Young Halevi had no need

to be angry, but sought to live fully and not as a victim.

After living in Israel for nearly 20 years, he set forth on a

search to better understand the practices, beliefs, and devotion of

the Christians and Muslims who lived in Israel and the West Bank. His

book, “At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew’s Search for God

with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land,” chronicles that journey

and the insights he gained as he joined the prayers and practices in

mosques and monasteries.

In 2013, his efforts to create meaningful dialogue led Halevi and

Abdullah Antepli, an imam and founding director of Duke University’s

Center for Muslim Life, to establish the Muslim Leadership Initiative

at the Shalom Hartman Institute. Each year they bring Muslim leaders

from North America to Israel to dialogue with rabbis and Jewish

leaders about Judaism and Israel. In 2016, Antepli and the president

of the Shalom Hartman Institute, Donniel Hartman, came to the Kaufman

Institute for a presentation on “Can We Find Common Ground between

Israel and Palestine?”

Halevi’s latest book is “Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor.” He

seeks to open a public conversation with his “neighbors” on the other

side of the division wall in order for both sides to better understand

each other’s narratives and hopes for the future. In a recent video he

explains, “One of the great dangers of our time is the breakdown in

our ability to argue passionately and respectfully with those with

whom we disagree.” This, he describes, is the situation in the Middle

East as he seeks a “new approach to the dysfunctional discourse”

currently dominating the efforts.

In his book he seeks to explain the Jewish people, their identity

and history, and why they return to their home. He recognized that

this is also the home to the Palestinian people. It is not an issue

of right vs. wrong, but right vs. right, as both parties seek their

legitimate goals. Both peoples belong deeply to the land, he asserts.

It is a balance between empathy and faithfulness to one’s own story.

Halevi sees himself living in the most dangerous part of the world,

“but not as victims anymore.” The challenge is to avoid being 100%

sure of your own position, for it is in that little space of doubt

where one can grow in understanding of the other.

Halevi had his book translated into Arabic and made available

free for download. He encouraged Palestinian and Arab responses which

he published in the second edition. While he was tempted to respond

himself to the responses he received, he chose to let them have the

last word. It is his goal to open up a new conversation of honestly

seeking to hear the stories of the other and seeking to understand

them. It might be a goal for all of us in the polarized environment

that seems to have captured much of our discourse these days.

The Kaufman Institute is beginning an online discussion group

next week on Halevi’s book. For further information see the notice or

go to our website at www.InterfaithUnderstanding.org

In these days of conflict and competing narratives, let us keep

open that space to listen and perhaps learn from someone who sees the

world through different eyes. It is an opportunity to learn and

perhaps take a step toward peace.

Posted on Permanent link for "An approach to Israel-Palestine understanding" by Doug Kindschi on July 14, 2020.

Permanent link for "Struggling with racism on the Fourth of July" by Doug Kindschi on July 7, 2020

I am writing this week’s column on the Fourth of July, not in a big

crowd watching fireworks, but quietly reflecting on our country, its

history – both the good and the bad.

Recent months have led many of us not to celebration, but to

challenge. We are challenged by a pandemic keeping us isolated and

apart. We have been opened to a new understanding of racism and

systemic problems in the police culture. We have had to face our own

complicity in allowing and even supporting systems of discrimination.

For me it has led to a time of confession and resolve to better

understand my own unconscious racism embedded in a “white privilege”

which had also been invisible to me.

During these days of celebrating our country’s founding, I

appreciate the privilege of living in a free country, realizing that

my freedom is not experienced in every nation. And not experienced by

everyone in our country – not at our founding and not even today. It

is a kind of “freedom privilege” that we take for granted. We are

rarely conscious of that privilege. In a similar way many of us have

benefited from white privilege of which we have not even been

conscious. It was just the way the world was. I went to excellent

schools, enjoyed meaningful jobs, didn’t worry about getting into

college. I was never threatened by a policeman. Growing up I just

assumed that was the case for anyone living in America and generally

law abiding.

Reggie Rivers, former NFL running back with the Denver Broncos

and now a broadcaster, author, and motivational speaker, illustrates

white privilege by telling about a white friend’s experience with the

police. His friend had left an event at the Four Seasons hotel and

was driving home when he saw the police lights flashing in his mirror.

On the busy street there was no convenient place to pull to the side

so at the next corner he turned right and then stopped. The

policeman informed him that he was driving without his headlight

turned on. He explained that he had been at an event at Four Seasons

and the valet parking attendant must have turned off his automatic

lights, of which he was unaware since the city street was quite well

lit. The officer went on to tell him that he had turned onto a

one-way street, going the wrong way and further asked if he had

anything to drink at the event. He responded that he had a couple of

drinks. The police officer then suggested that he do a U-turn and park

his car in the right direction and then take an Uber ride home.

Rivers’ response was that this could never, in any way, have been

his experience as a Black person. “Driving while Black” means always

subjected to being pulled over on some minor charge and then

interrogated in a way that almost seems designed to infuriate. It was

certainly not the experience of Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta, who was

guilty of “sleeping while Black” in his car at a Wendy’s drive

through. Even though he cooperated for over 20 minutes, submitting to

a breath test as well as a pat-down. He moved his car, volunteered to

leave the car and walk to his sister’s house. Only when the police

became physical and tried to handcuff him and take him in did he

resist, resulting in a conflict that led to his being shot in the back

while running away.

White privilege includes a lot of benefits that most of us have

not been aware of as we go through life. We unconsciously assume that

this is just way things are. As a child I was not followed by police

when I rode my bike outside my immediate neighborhood. When I began to

drive, my parents didn’t instruct me to always keep my hands on the

top of the steering wheel if I got stopped by police lest they think I

might be reaching for a weapon. I was taught that police were there to

help me if I was in trouble and that I could trust them. Only when

recently learning about white privilege did I begin to see its

invisibility to me most of my life.

In another video Reggie Rivers tells of a retreat he had with 34

other Black men. He describes them as very successful, educated, and

wealthy. As they began telling their stories, he was amazed at the

similarity of their stories and their feelings about what was now

happening in America. He was shocked as they described their

experiences and that no matter how much success or education or wealth

they had, when they get stopped while driving they are “just another

black guy in the car.” He polled them to discover that among this

group, ages in the 20s to 60s, most of them were college graduates and

28 were CEOs or senior executives.

He continued asking how many feared the police: 29 responded yes.

All 34 had been threatened or baited by police and had in just the

last 12 months been profiled in a store or by police. Furthermore,

everyone was surprised that the murder of George Floyd has led to such

a broad appreciation and understanding from people of all backgrounds.

America is waking up to what has been happening, but what for many of

us has gone unseen.

You can watch these videos for yourself at: https://virtualgalateam.com/racism

Racism is a phenomenon also similar to religious bigotry and

hate, which our culture has experienced in the past and continues

today. Catholics and Jews were persecuted and faced hatred, as did

various immigrant groups. Anti-Semitism has been prevalent in our

history and recently led to the murder of 11 congregants at the Tree

of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Islamophobia targets peaceful

Muslims and even people who are mistakenly seen as Muslim because of

skin color or dress such as the turban-wearing Sikhs. In each case it

is the “othering” of people who do not look like, dress like, or

worship like my tribe. This attitude violates the teachings and

principles of all of our religious scriptures, but is still prevalent

in our society.

The Kaufman Interfaith Institute will begin a new book club on

Zoom discussing the book “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White

People to Talk about Racism” written by Robin DiAngelo. She helps us

understand why cross-cultural dialogue is so hard and why our

defensiveness actually adds to racial inequity. For

more information go to www.bit.ly/Kaufman-Book

We are at a special time in America today. As we move forward

from July Fourth let us work toward a new freedom that includes all

regardless of race, religion, skin color, economic status, and social

standing. This is a special time when more of our society is becoming

aware of previous failures. It is time to show commitment to finding

justice and support for all peoples.

Posted on Permanent link for "Struggling with racism on the Fourth of July" by Doug Kindschi on July 7, 2020.

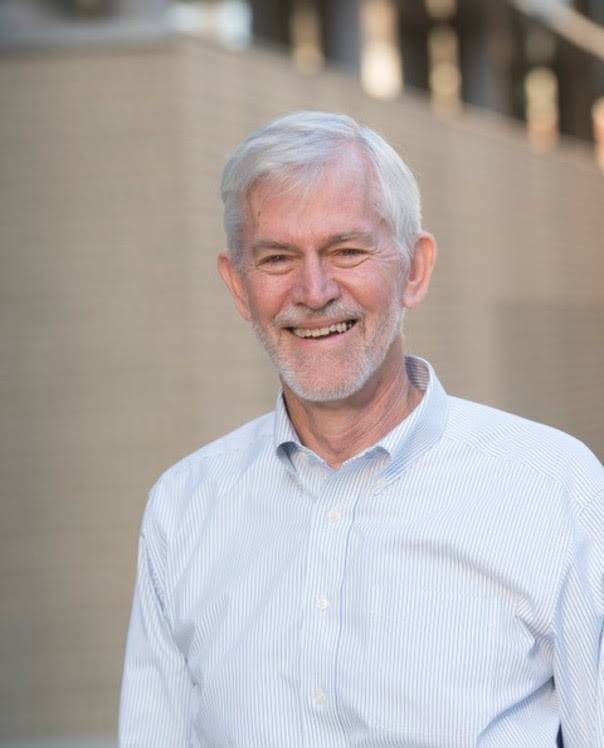

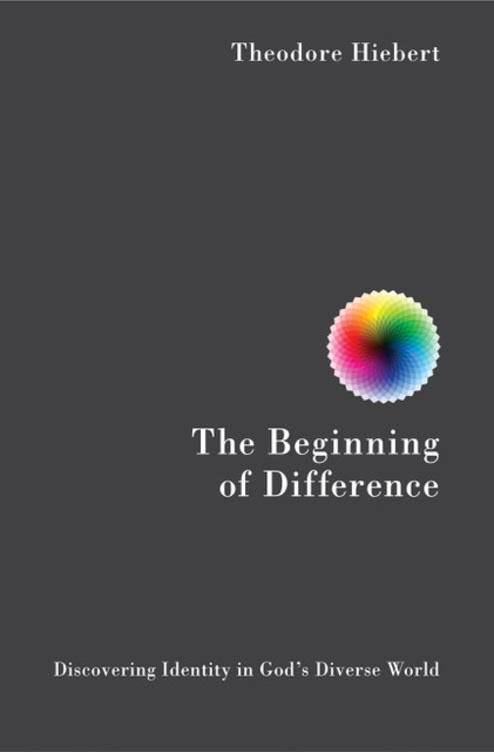

Permanent link for "The beginning of difference - God's idea" by Doug Kindschi on June 30, 2020

“Difference can be a source of vast enrichment and growth — or a

reason for hate, exclusion, discrimination, and violence. … The stakes

of difference are high.” So writes Ted Hiebert, Professor Emeritus at

McCormick Theological Seminary, in his recently published book, “The

Beginning of Difference: Discovering Identity in God’s Diverse World.”

Our understanding of difference is critical in these days of

racial discrimination, fear of immigrants and refugees, political

polarization, and even hate. Religious differences as well contribute

to anti-Semitic and Islamophobic attitudes and actions.

Hiebert received his doctorate at Harvard University and taught

there as well as at Gustavus Adolphus College, Boston College and St.

John’s University. At McCormick he was the professor of Old Testament,

one of the editors and translators of the Common English Bible, and

wrote commentaries on Genesis for multiple publications.

He explores the issues of identity and difference in the book of

Genesis as well as in the contemporary scene. In today’s world,

identity and difference are frequently defined by religion and skin

color. Our history and early texts help form our current attitudes,

and Hiebert explores the origin stories of difference as expressed in

the biblical book of Genesis.

The various Genesis authors seek to understand identity and

meaning for the emerging Hebrew people. The famous story of the “Tower

of Babel” as recorded in Genesis 11 has often been interpreted as a

story of human pride and God’s punishment. Hiebert wants us to look at

this short passage with new eyes. This familiar story, comprising just

nine verses, is in two distinct parts. The first four verses describe

the people taking bricks and mortar to build a city and a “tower with

its top in the sky, and let’s make a name for ourselves.”

Hiebert notes that there is nothing in these verses that

indicates pride. Rather, it as a story about a people seeking to

create and preserve their own cultural identity. He writes, “I believe

the beginning of the story of Babel is dealing with … (an) important

human experience — the need for meaning, belonging, and identity that

can only come from being a member of a common cultural tradition.” He

sees it as recognizing the fundamental need for social identity that

is common to all of us.

The reference to building a tower, which some translations

describe as “reaching to the heavens,” could also be translated as

“reaching to the sky.” Hiebert, a Hebrew language scholar as well,

prefers this latter translation and notes that it does not imply pride

but just that it would be very tall, much as we might describe a “skyscraper.”

Thus, the first part of the story represents the normal and

appropriate desire to find identity in one’s community and culture.

The second part of the story, verses 5-9, describes God’s

response. While the people were constructing a single culture, God

introduces multiple cultures. Hiebert writes, “God introduces

difference. How we understand what God intended and what God did when

God brought difference into the world will have everything to do with

how we understand the message of this story about difference.”

A common language is a primary marker of a distinct culture, and

God brings a diversity of language in order to introduce multiple

cultures. The story tells us how God mixes the languages so they

cannot understand each other. Some translations describe this as God

“confuses” their language, while other translations use the work

“mixes” or “mingles” their languages. Hiebert prefers this latter

translation since it is more neutral. There is nothing in the text

about this being a punishment; it is just the action taken. It is one

of the ways God creates multiple cultures.

The story goes on to say that God scatters them across the earth.

Geographical location is another marker of a culture and thus God

creates difference in both language and common living space.

In these origin stories recorded in Genesis we find insights that

can inform the issues of today. The drive for identity and common

cultural affiliation is a natural human need. But the reality is that

we live in a world of many cultures. We can choose to see this as

threatening or we can see it as a reality ordained by God.

It is natural to seek identity with those we see as having

something in common, and certainly language and living space are

important parts of that commonality. We often also seek our identity

with those with whom we share religion, political ideas, professional

interests, hobbies, etc. These identities can be very useful and

healthy. But when the identities become overbearing and exclude those

with different identities they can become hurtful and even lead to

hate and violence.

In the current political environment it is important to recognize

that seeking identity is a natural desire. Yet our country is founded

on diversity and throughout our history this struggle has led to

conflict between various ethnic and religious groups. Catholics, Jews,

Irish, Asians, Muslims, Blacks and others have all been subjected to

discrimination and prejudice because of their identity. By

understanding our scriptures, as well as the aspirations at our

country’s founding, we can see more clearly the vital role of

diversity in our world.

Based on the reading of our religious origin stories, we see the

different cultures and identities as a part of God’s plan for

diversity. This insight can lead to understanding, acceptance, and

peace. Hiebert writes, “The drive toward identity and solidarity is a

distinctively human impulse, and the emergence of difference as a

distinctively divine choice. … Difference is God’s idea.”

In these days of division and hatred, let us embrace difference

in order to learn, grow and find meaning in the rich variety of

identities. “Difference is God’s idea.”

Posted on Permanent link for "The beginning of difference - God's idea" by Doug Kindschi on June 30, 2020.

Permanent link for "A personal confession: I am a racist" by Doug Kindschi on June 23, 2020

As a child I had very positive contacts with African Americans, never

recall telling a racist joke or using the “n-word.” As an adult I

have tried to support equality for all, had excellent relationships

with Black colleagues, and supported Black Lives Matter. But the

recent events have shocked me into realization of how deep the

systemic racism is in our society and how my eyes are being opened to

its pervasiveness.

In the interfaith world I am quite aware of how racial hatred is

related to anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. They all represent a

built-in bias against people whose looks, dress, and worship are

different. Our cultural institutions and foundational documents are

supposed to lead us to respect all people. “Liberty and justice for

all,” “All men are created equal, endowed by their creator with

unalienable rights,” “government of the people, by the people, and for

the people,” etc. But in reality they seem to be aspirations that do

not work out in practice.

Our religious scriptures teach us that we are all created in the

image of God, that we are to love our neighbors and even our enemies,

and yet religious institutions are often segregated by race and

perpetuate practices that do the opposite of our religious teachings.

As a white person I was taught that our police were to protect us

and keep us safe. Even when stopped for a traffic violation

(fortunately not in the past few decades) I never had to fear being

shot. Unfortunately, my experience has not been that of those

growing up and living in Black communities, or being Black in

predominantly white communities. The “warrior police” has more likely

been their experience. Of course not all police are bad, and of

course there are bad actors in the force, but even good people in a

bad system can get caught up in denial, participate in group think,

and get carried away with resorting to use of deadly force.

We should remember that early on police had the task of tracking

down escaped slaves and returning them to their masters. Is this

attitude of treating Blacks as property rather than persons still an

unconscious factor in the police culture? Property is to be controlled

and made to serve the owner. Putting on the police uniform can also be

putting on a historical mindset.

The era of cell phone cameras has let us all witness events of

police brutality, blatant murder and provocations that escalate to

physical struggles leading to someone being shot in the back. What was

for many a fact of everyday life has now been graphically exposed for

the world to see: the systemic racism in our country.

In addition to the daily news stories, I have watched two videos

that have given me new insights in understanding our situation.

The film “Just Mercy,” released last year in theaters and now

available through many streaming services, vividly depicts a

Harvard-educated Black lawyer being subjected to the very kind of

treatments that were everyday experiences for others in his minority

community. The film is based on his book describing his day-to-day

experience while working with prisoners on death row in Alabama. His

encounters with police and prison officials, while attempting to do

his work, help me understand the recent news reports from Minneapolis

and Atlanta. It also helps me understand why Black persons convicted

of murder are 11 times more likely than whites to receive the death

penalty, and that as many as one in nine on death row are actually innocent.

This movie is now available for free on many major web streaming

websites such as Google, Amazon, Netflix, etc.

Kaufman Interfaith Institute included it in this month’s cinema

discussion series, held this week. You can get more information about

the film and our online discussion by going to our website: www.InterfaithUnderstanding.org.

My other video experience this past week was the talk given by

Willie Jennings at last year’s January Series at Calvin University.

Jennings, raised in Grand Rapids, is a Calvin graduate with a master’s

degree from Fuller Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. from Duke

University. He is now a professor of theology at Yale University.

Jennings makes the connection between racism and geography, of how our

hopes and dreams are tied to our location, our immediate environment.

His talk takes us back to the dreams of the early European

settlers who saw the wide-open spaces as an opportunity to possess the

land and turn it into what would sustain and provide value to them

personally. They looked down on Native Americans as naïve in their

living with the land rather than seeking to possess and control it for

their personal benefit.

Jennings sees this relationship to geography and one’s

environment as key to understanding the systemic racism in our country

today. It goes back to this early white-European vision “based on

mastery of this world, control of its land and resources and a freedom

to live unencumbered by anyone.” Such a control was fundamental to

slavery society. He sees it present as well in geographic restrictions

from zoning and financial constraints, to the actions of real estate

brokers and the police.

You can watch his presentation at: www.bit.ly/Calvin-Jennings

I am now striving to be a “recovering racist,” one who recognizes

the problem and seeks to make corrections. I am seeing more clearly

how our society and many of its institutions have been built on a

racist premise, and I am discovering my own invisible complicity with

that system that dehumanizes large segments of our population.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said, “In a free society some are

guilty, but all are responsible.” I am not guilty of killing George

Floyd or for the shooting of countless Blacks in our society, but I

must take responsibility for my role in a society and its institutions

that make these acts too commonplace.

I don’t want to be racist, or even non-racist. I want to be

anti-racist. The path is not totally clear to me. But I believe it

begins with confession, and with increased awareness of society’s

institutions and assumptions that permit hatred based on race, skin

color, immigrant or refugee status, or religious practice.

Posted on Permanent link for "A personal confession: I am a racist" by Doug Kindschi on June 23, 2020.

Permanent link for "Faith communities call for racial justice: A Jewish reflection" by Allison Egrin on June 16, 2020

Note from Douglas Kindschi, Director

Faith communities from Minneapolis to Washington to the Vatican have joined the chorus responding to the protests with calls for racial justice. Evangelical responses in Minneapolis included helping in the clean up efforts. In Washington D.C. conservative churches led a march supporting Black Lives Matter, and Senator Mitt Romney joined the effort. Pope Francis denounced what he called “the sin of racism” while referring to the killing of George Floyd. He addressed all Catholics saying, “We cannot close our eyes to any form of racism or exclusion, while pretending to defend the sacredness of every human life.” The Islamic Society of North America unequivocally condemned the “horrific death of George Floyd,” and its president, Dr. Sayyid Syeed said, “Incidents like this go against the very fabric of our nation and the ideals we hold so dear.”

Other faith communities representing Bahai, Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist traditions have likewise condemned the murder of George Floyd and called for action to end racism. In today’s Insight, Allison Egrin from our Kaufman Interfaith Institute staff relates a recent online discussion sponsored by the Coalition for Black and Jewish Unity.

On June 4, I attended a Zoom call hosted by the black-Jewish coalition sponsored by the Detroit chapters of JCRC (Jewish Community Relations Council) and AJC (American Jewish Committee) called “Dear White People, Please Listen.” The Zoom was hosted by several clergy, bishops, and pastors who were there to call on the local Jewish community to stand by them and support them in dismantling systemic racism. Each leader spoke out about what their own thoughts and struggles were and gave tangible ideas and actions for what we can do to support them. As a white Jewish female from metro Detroit, my first takeaway was the importance of mutualism in activism. Activism is a two-way street.

On the Zoom call, many of the speakers reminded us that the black community shows up for the Jewish community when it comes to lobbying for Israel and for standing up against anti-Semitism. I have seen this personally with my own eyes at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee convention in D.C. I have seen the large turnout of black evangelicals there to lobby and stand with us to support our country and to fight against anti-Semitism.

As a Jewish woman, I have felt the deep support of other communities in the face of anti-Semitism. After listening to the call, I am asking myself and my Jewish community, what are we doing when those same supporters need us to stand up with them? Furthermore, what can our broader interfaith community be doing? It is not just on the Jewish community to support our black brothers and sisters, but also on every community with the means or privilege to do so.

It is not enough to just simply “stand by” and physically be there for the black community. Ibram X. Kendi, author of “How to Be an Antiracist,” once said, “What’s the problem with being ‘not racist’? It is a claim that signifies neutrality: ‘I am not a racist, but neither am I aggressively against racism.’ But there is no neutrality in the racism struggle. The opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘antiracist.’”

It is not enough to not be racist anymore. We must work towards becoming antiracist, to fight this long-overdue fight. A 400-plus-year-old fight, to be specific. Our neighbors, our friends, our brothers and sisters deserve this from us. You can’t have activism without action.

The speakers on our Zoom call gave clear actionable steps for us to take, and while they may not seem quick or easy, they are vital in getting this work done.

Challenging our friends and family members when they say something that they shouldn’t, or calling out people when they need to be called out, is not a comfortable thing. At Kaufman, we also say the worst thing you can say during a conversation is “agree to disagree” because it ends the conversation. In order to really be an ally and advocate, we cannot be satisfied with agreeing to disagree. The conversations must not end.

Challenge your friends. Have those uncomfortable conversations at the dinner table. That is how we can all actively be antiracist in our day-to-day lives. Consider who you are voting for. Where do they stand when it comes to racism? Is your company voicing their opinions right now or sitting idly by? Are the companies you are purchasing from doing the same?

Most importantly, I encourage you to listen. Listen to your peers. Listen to what they need and are asking of you. I encourage you to learn. Seek out literature, television, movies, and documentaries that elevate black narratives.

This work is not easy and it cannot be done alone. We all must come together to dismantle our own internal biases, fight for change, educate the younger generations to continue this work and to not stop until every life is treated equally. This work is a constant and it’s a must. It cannot end when the news cycles change to another topic. This must be an active, persistent, and conscious effort. It isn’t enough to go to one protest, make one donation, or have one uncomfortable conversation. We must continue until the work is no longer needed.

If you ask yourself the same thing I did -- “Why me? What position am I in to be sharing my thoughts?” – consider this from the Jewish proverb, Pirkei Avot 1:14: “If not now, when? If not me, who?” Hillel the Elder says this as a call to action in Bible times. Now, it cannot be more relevant in regards to racism in America. It is on all of us to speak out against racism, to fight for equality, and to fight for our black brothers and sisters in these urgent times.

All lives can't matter until Black Lives Matter. We must never fail to act when we witness bigotry, racial discrimination, or the devaluing of human lives. Most importantly, we must get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Permanent link for "Amid racism and protests, can we find hope?" by Doug Kindschi on June 9, 2020

Racial justice is certainly the critical issue we face today. The

pandemic of racial injustice has even pushed aside the coronavirus

pandemic. The murder of George Floyd and the worldwide response has

brought this issue again to our consciousness. It also begs the

question of how will faith communities will respond.

The response has been strong and widely diverse, from the

Parliament of World Religions to the evangelical journal “Christianity

Today.” The Parliament joined with other organizations like Religions

for Peace to issue a joint statement titled “This Perilous Moment.”

It reads, in part:

Our words come in an hour of peril informed by a sense of crisis.

Racial injustice, deep inequities, hate speech, brutality, and

authoritarian power converge in a vulnerable moment when millions are

infected and affected by a global virus that we have yet to find

either a vaccine for or any medication to deliver us from. This

endangers the fabric of our society.

Our wicked scourge of discrimination and racism is structural,

systemic, systematic, and institutional. …We soberly own up to the

fact that our religious communities have been complicit for far too

long. We have upheld in far too many ways the false tenets that enable

racism to continue in our society.

We confess that we have a sickness in America that is spiritual

and moral in nature even in as much as it is cultural, economic,

political, and social. Our sacred texts and traditions have been used,

wrongly so, to further racial injustice. Yet, they are also a deep

well that informs our understanding of justice, and which can now call

us all towards our better angels to overcome this crisis. People

of faith must stand for love and stand up for equity, equality, and justice.

Christianity Today also addressed this issue in a May 28 article,

“George Floyd Left a Gospel Legacy in Houston.” It points out that

Floyd, before moving to Minneapolis two years ago, lived in Houston

for decades where he mentored young men to break the cycle of

violence. He was known as “Big Floyd” at a housing project where he

“used his influence to bring outside ministries to the area to do

discipleship and outreach.” Pastor Patrick Ngwolo of the Resurrection

Houston church said, “George Floyd was a person of peace sent from the

Lord that helped the gospel go forward in a place that I never lived in.”

One of Floyd’s friends there said, “I think he wanted to see

young men put guns down and have Jesus instead of the streets. … The

people who knew him personally will remember him as a positive light.

Guys from the streets look to him like, ‘Man, if he can change his

life, I can change mine.’”

The response to Floyd’s murder swept the nation and even

countries around the world. Longtime advocate of racial justice and

founder of the evangelical journal “Sojourners,” Jim Wallis wrote, “In

my lifetime, I have never seen more white people involved in the deep

and growing movement to address systemic racism, structural injustice

on many fronts, and, specifically, the violent policing and killing of

black people. … Thousands of mostly young people — diverse across

faiths and ethnicities — were exercising their power to protest. I

have never … seen so many white people who care so deeply about

America’s Original Sin, structural racial injustice, and the 400 years

of violence against black lives, following the lead of their black

brothers and sisters to voice that concern to the police and military,

and all the political leaders behind them.”

Another posting from Christianity Today reported how the

evangelical churches of Minneapolis have joined together in protesting

racism and police violence, as well as participating in citywide

efforts to donate food and supplies and recruit volunteers for cleanup

efforts. An organization of evangelicals called “Transform Minnesota”

has led efforts to address social issues in the community. A black

Baptist pastor told the group, “Yes, we need your help right now. Yes,

we need your help cleaning up. Yes, we need your resources. But we

also need long-term partners who are going to help us stand up for God

and tear down the systems that hold people down.”

Greg Boyd, senior pastor at the evangelical megachurch Woodland

Hills in the Minneapolis area, was also reported to have told a group

of pastors on a Zoom call that he was “convicted that racism is the

responsibility of the white church. If white Christians had loved like

Jesus loved,” he said, “they could have stopped slavery before it

began, squelched the Ku Klux Klan, and prevented the laws that

instituted racial segregation in America.”

Jewish and Muslim groups have also mobilized and raised money for

the racial justice efforts and recognize the affront that racism has

been to these religious communities as well. Leaders gathered together

this last Sunday afternoon for an online interfaith forum on “Police,

Prejudice, and Prophetic Paradigm” sponsored by the Islamic Society of

North America.

When asked “What is your best cause for hope today?,” Atlanta

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms called for a “monumental shift” in order to

“signal to our country that it is time to heal.” She added, “I am so

inspired when I see protesters across this country and see police

kneeling with protesters across the country because they are saying to

each other, 'I hear you, I feel you, and I want something better for

our country too.'"

Is this a turning point for our nation? Can we find hope in the

developments that have occurred?

I do find hope in the number of police leaders from Flint and

Houston, and now in Grand Rapids, who have met with the protesters,

shared their concern, marched with them, and even “taken the knee.” I

take hope in the protests that have not only swept the entire country

but have gone worldwide to places like England, Germany, and New

Zealand. I find hope in pastors from all religious affiliations who

are in words and actions addressing this 400-year blight on our

society. I find hope in the many faith traditions that have initiated

cooperative commitments bringing their scriptures and beliefs to work

together for needed action.

We cannot hide from the truth taught by Rabbi Abraham Joshua

Heschel, “that in a free society, some are guilty, but all are

responsible.” We may not be guilty of George Floyd’s murder, but we

are all responsible for systems that perpetuate racism, tolerate abuse

of authority, and for our failure to act on our religious and ethical

imperatives to love justice and mercy for all.

Posted on Permanent link for "Amid racism and protests, can we find hope?" by Doug Kindschi on June 9, 2020.

Permanent link for "Rights and responsibility, how does one act?" by Doug Kindschi on June 2, 2020

"Is it my responsibility to speak?" is a better question

than "Is it my right to speak?" So wrote Justin Meyers in a

recent Facebook blog. Meyers is a minister in the Reformed Church in

America who serves as the associate director of the Al Amana Center in

the country of Oman, an interfaith center in this Muslim country in

the Middle East. He is also a graduate of Grand Valley State

University before going to seminary to pursue his theological education.

In his post Meyers was sharing what he called “one of the most

important shifts in my life,” when a seminary professor encouraged him

to think more about responsibility than about one’s rights. Of

course, rights are important in a free society but the issue is “how

and when we claim these rights.”

Meyers continues, “Rights are self-focused, responsibility is

community focused.” He then applies it to our situation today by

posing the following questions:

1. Is it responsible to go out?

2. What ways can I responsibly speak out for those who are suffering?

3. Are there ways I can make my point in responsible ways that

won't cause more harm?

4. Is what I am doing going to benefit others who aren't me (and

my "tribe") and those who are unable to be heard?

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks made a similar point in a recent BBC

interview. The former chief rabbi of Great Britain said, “We’ve had

too much individualism … and too little concern for the collective of

the nation and for humanity as a whole. We have talked far too much

about rights and far too little about responsibilities … Without

responsibilities in the end you find you have no rights.”

Sacks is quick to point out the true heroes who have acted

including the “doctors, nurses, responders, and the public accepting

the responsibility.” He is also positive about what can emerge from

this shared experience noting, “There is something within us, as

social animals, that makes us feel better when we are altruistic, when

we help others, when we make their life better. ...We will come

through it with a much stronger identification with others.”

Last week we honored those brave members of our society who

actually gave their lives to protect our liberty and freedom. I

watched a Memorial Day video tribute that included the playing of

“Amazing Grace” on bagpipes and showing scenes of brave soldiers, many

of whom gave their lives for our freedom. That freedom of course

includes our rights, but I shudder to think that what it is about for

some is the freedom to endanger the health of others by my behavior,

or the freedom to bully someone with whom I disagree. Our rights and

freedoms we consider to be sacred, but let us not squander them on

trivial matters of selfish behavior.

An early champion of freedom was written by the English

philosopher, John Stuart Mill in his 1859 essay “On Liberty.” Mill

defined liberty as living “one’s own life in one’s own way.” But in a

recent essay, University of Chicago Professor of Theological Ethics

William Schweiker notes that Mill recognizes a “rightful boundary to

one’s liberty.” He writes that Mill calls it the “harm principle — my

liberty goes only so far as it does no harm to others … and that

liberty without boundaries is chaos or war.”

Schweiker reflecting on our situation today writes, “Competing

notions of liberty in our nation are routinely divided and named: blue

versus red states; right versus left; … liberal versus conservative;

journalism versus fake news, and on and on. Each side accuses the

other of causing (and exacerbating) the division; all while each side

believes itself to represent the true spirit of the nation. But as

Lincoln rightly noted — citing scripture — a house divided cannot

stand. As it was in his time, so too is it in ours.”

But what is the role of religion in our currently divided

situation? Schweiker responds, “Whether it is the Exodus and Sinai,

and so the giving of law for a life in freedom, or the so-called

Golden Rule, the teachings of Jesus, the holy Qur’an, or the Buddha’s

middle way, the religions have sought to hold in tension freedom and

liberation with a rightful submission to the law of other-regard.”

In this week’s Christian Century, editor/publisher Peter W. Marty

affirms the importance of rights, but asks, “If I see my life

primarily as a prepackaged set of guaranteed rights owed me, instead

of as a gift of God, what motivation is there to feel deep obligation

toward society’s most vulnerable? If I’m just receiving what’s my

rightful due, why would I ever need to express gratitude? What’s the

point of looking outward toward others if I’m chiefly responsible for

looking inward and securing the personal rights that are mine?”

Rabbi Sacks is actually quite hopeful that our current crisis

will bring us together for the common good for all of humanity. In his

interview he continues, “We’re coming through this feeling a much

stronger sense of identification with others, a much stronger

commitment to helping others. This, in a tragic way, is probably the

lesson we needed as a nation and as a world.”

Richard Rohr, widely recognized ecumenical teacher, Christian

mystic, and Franciscan monk, also sees our current situation as an

opportunity. He wrote, “If God wanted us to experience global

solidarity, I can’t think of a better way. We all have access to this

suffering, and it bypasses race, gender, religion, and nation.” He

calls it a “highly teachable moment.”

It is up to each of us to weigh carefully our responsibilities in

our current situation against the desires for a kind of freedom that

could bring harm to others. It involves not only what it means to be a

good citizen, but also what our faith commitments require of us.

Posted on Permanent link for "Rights and responsibility, how does one act?" by Doug Kindschi on June 2, 2020.