STORY BY THOMAS CHAVEZ

When military veterans transition from combat zones to civilian life, they face a new battlefield: Finding normalcy. Many face long-term health challenges stemming from their deployments, both physically and mentally. They must navigate the system to acquire their benefits and acquaint themselves with a life they did not experience during their term of service.

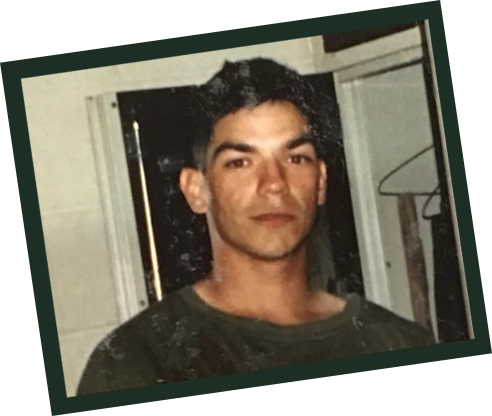

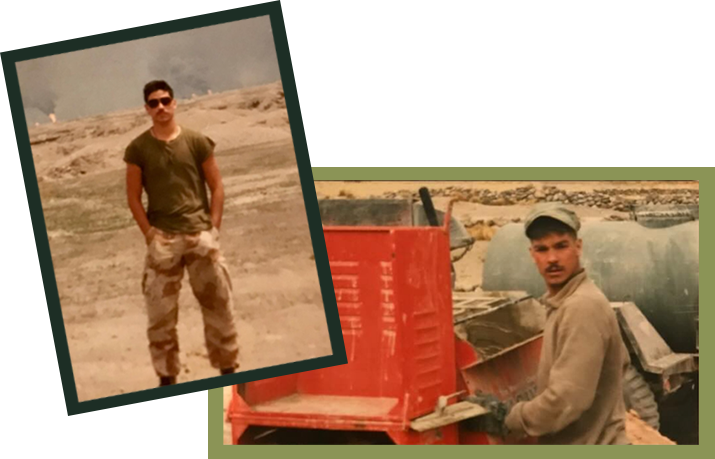

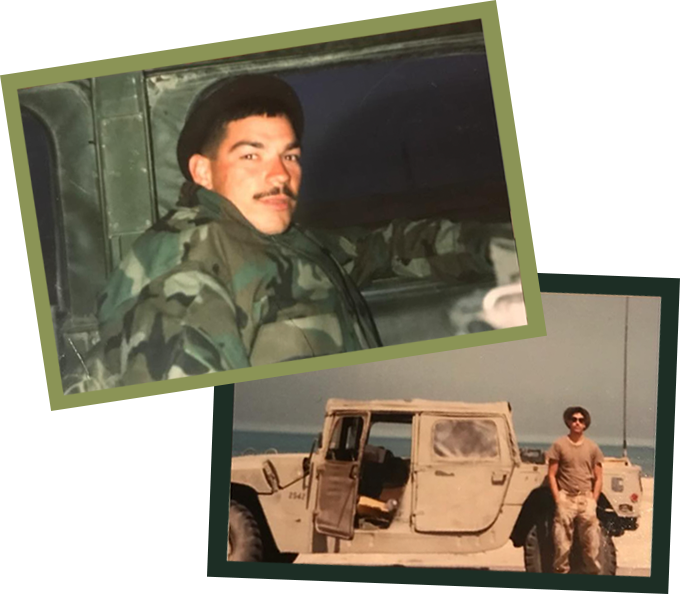

Melissa Villarreal, an associate professor of social work at Grand Valley, saw her brother face these challenges firsthand after he was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps. The veteran from Operation Desert Storm returned to the United States, dealing with post-traumatic stress, a traumatic brain injury and other health issues that resulted in ulcerative colitis.

Villarreal’s brother faced difficulties in receiving health benefits. Ulcerative colitis is not a covered medical condition for Iraq veterans. In her attempts to assist him, Villarreal experienced what it was like trying to navigate the Department of Veterans Affairs system.

“Just in helping him and feeling frustrated, angry and not understanding why they don’t listen to him made me think that other people must be going through the same thing,” said Villarreal. “People need to know. We need to do all that we can.”

Inspired by her brother’s challenges, Villarreal began research on combat veterans, primarily from Iraq, Afghanistan, among other conflicts. Her research, “Voices of Combat Veterans: Perceptions, Needs and Experiences,” focuses on giving veterans a voice to discuss their experiences with medical and mental health conditions that resulted from combat.

Villarreal’s research is an ongoing effort, creating many questions to build off each other. She presented her research in August 2024 at a conference in Montreal. As she prepares for future presentations, she is focusing on veterans’ experiences returning to civilian life.

IMAGE CREDIT - COURTESY PHOTOS

STORY BY THOMAS CHAVEZ

When military veterans transition from combat zones to civilian life, they face a new battlefield: Finding normalcy. Many face long-term health challenges stemming from their deployments, both physically and mentally. They must navigate the system to acquire their benefits and acquaint themselves with a life they did not experience during their term of service.

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Melissa Villarreal, an associate professor of social work at Grand Valley, saw her brother face these challenges firsthand after he was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps. The veteran from Operation Desert Storm returned to the United States, dealing with post-traumatic stress, a traumatic brain injury and other health issues that resulted in ulcerative colitis.

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Villarreal’s brother faced difficulties in receiving health benefits. Ulcerative colitis is not a covered medical condition for Iraq veterans. In her attempts to assist him, Villarreal experienced what it was like trying to navigate the Department of Veterans Affairs system.

“Just in helping him and feeling frustrated, angry and not understanding why they don’t listen to him made me think that other people must be going through the same thing,” said Villarreal. “People need to know. We need to do all that we can.”

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Image credit - Courtesy photo

Inspired by her brother’s challenges, Villarreal began research on combat veterans, primarily from Iraq, Afghanistan, among other conflicts. Her research, “Voices of Combat Veterans: Perceptions, Needs and Experiences,” focuses on giving veterans a voice to discuss their experiences with medical and mental health conditions that resulted from combat.

Villarreal’s research is an ongoing effort, creating many questions to build off each other. She presented her research in August 2024 at a conference in Montreal. As she prepares for future presentations, she is focusing on veterans’ experiences returning to civilian life.

Helping Villarreal in her research is graduate assistant Nicholas Stevenson, ’23. Stevenson assists Villarreal in interviewing and building the research literature, and he will ultimately present their findings at upcoming conferences. Villarreal said she tries to treat him like a colleague in their work together, and Stevenson said he is grateful for the experience.

“You take research classes and you get an idea of how research is done,” said Stevenson, who plans to graduate with a master's degree in social work in April. “But you don’t actually get to do the research a lot of times. So it is a privilege to see that happen.”

Villarreal and Stevenson understand the sensitivity of the nature of the research they are conducting, and they have made the effort to make the veteran volunteers as comfortable as possible during the interview process.

Villarreal’s background as a child and family therapist, as well as extensive research on various sensitive topics, has helped her create a space where the interviewees feel safe to speak.

“I get nonverbals. It is what helps me the most,” Villarreal said. “I can tell if somebody is uncomfortable or they’re angry or feeling really anxious.”

Graduate social work student Nicholas Stevenson is working with Melissa Villarreal, associate professor of social work, on a research project involving combat veterans’ experiences of mental and medical health care issues. Stevenson said the research has shown him that we need to put more care into how we treat veterans. (Photo by Kendra Stanley-Mills)

Helping Villarreal in her research is graduate assistant Nicholas Stevenson, ’23. Stevenson assists Villarreal in interviewing and building the research literature, and he will ultimately present their findings at upcoming conferences. Villarreal said she tries to treat him like a colleague in their work together, and Stevenson said he is grateful for the experience.

“You take research classes and you get an idea of how research is done,” said Stevenson, who plans to graduate with a master's degree in social work in April. “But you don’t actually get to do the research a lot of times. So it is a privilege to see that happen.”

Villarreal and Stevenson understand the sensitivity of the nature of the research they are conducting, and they have made the effort to make the veteran volunteers as comfortable as possible during the interview process.

Villarreal’s background as a child and family therapist, as well as extensive research on various sensitive topics, has helped her create a space where the interviewees feel safe to speak.

“I get nonverbals. It is what helps me the most,” Villarreal said. “I can tell if somebody is uncomfortable or they’re angry or feeling really anxious.”

“I think the experience can be therapeutic but also can be scary.”

Nicholas Stevenson '23, graduate assistant

Stevenson said the allowance of anonymity in the study helps veterans feel more comfortable opening up as well. He said it was crucial to create a safe space for the veterans to talk about uncomfortable experiences in their lives.

“Sometimes the veterans that we’ve interviewed, maybe that is the first time that they’ve ever been asked those types of questions or ever thought about those types of things. So, I think the experience can be therapeutic but also can be scary,” he said.

Villarreal and Stevenson have found a balance of empathizing with the veterans during interviews and keeping to the required agenda of a research study. As veterans open up to discussing their experiences, they may stray from the topic, and Villarreal and Stevenson do their best to bring the conversation back to their questions.

“As a clinician, I want to be able to do that for them,” said Villarreal about the veterans going off topic. “However, as a researcher, I don’t want to go off tangent because I need to gather the information. It’s tough to stick to the agenda, especially when somebody is willing to share their story.”

Villarreal said that she balances these desires by making herself available to discuss the other topics a veteran wants to touch on after the research interview is complete.

In their research, Villarreal and Stevenson discuss the good and the bad with combat veterans. Villarreal said she hopes her research will help veterans find their voice and create systemic change in how they can continue building a better structure for benefits for themselves and those veterans to come.

“We need to start acknowledging the fact that their needs are not being met the way they should be,” Villarreal said. “We all have to stand together.”