Compelling Visions: The Art of Narrative in Japanese Prints

Kirkhof Center Wall Gallery, Allendale Campus

October 20, 2023 - March 15, 2024

Richard M. DeVos Center Wall Gallery, Robert C. Pew Grand Rapids Campus

July 5 - December 13, 2024

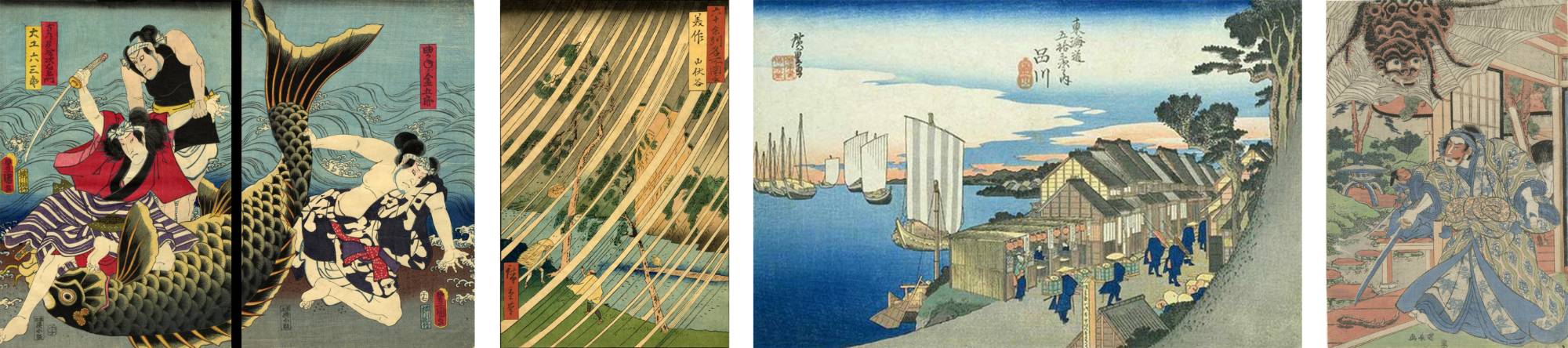

Utagawa Kunisada, The Carpenter Rokusaburo Catching the Carp, ca. 1850, L11.2022.22ab, Promised Gift of Charles Schoenknecht and Ward Paul, Utagawa Hiroshige, Mimasaka Province, Yamabushi Valley: Sixty-odd Famous Views of the Provinces (no.46), 1853, L11.2022.547, Promised Gift of Charles Schoenknecht and Ward Paul, Utagawa Hiroshige, Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido: Shinagawa (no.2), ca. 1833-34, 2011.96.2, Utagawa Kuninaga, Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raiko) and His Retainers Defeat the Earth Spider (left sheet of triptych), 1829, 2021.33.1933, Gift of Charles Schoenknecht and Ward Paul.

There is a long history of storytelling in Japanese art. Whether through the influence of tales about aristocratic courts from classical literature, the re-telling of heroic warrior epics from folktales, or the relaying of travel and pilgrimage through the landscape, Japanese artists have embraced narrative in their work. For centuries it included painting on scrolls, fans, books, and folding screens, as well as the decoration of garments, objects, and furniture for the elite. However, with the widespread adoption of printing technology in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Japanese artists began to translate their ideas into woodblock prints. This new media allowed Japanese artists to produce multiple copies at affordable prices, quickly resulting in a growing dissemination of their artwork to a wider and increasingly literate audience.

The growth of printmaking coincided with the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, a rather peaceful time when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and relatively isolated from the outside world. Major roads were built, linking cities and important religious sites, and the capital was moved to Edo (now Tokyo). It was also an era when the arts, travel, and entertainment became increasingly available to the middle class, and urban populations had the means and leisure time to support these activities. Artists responded with prints that embraced this pleasure-seeking lifestyle, often referred to as Ukiyo-e (floating world), depicting courtesans, actors, geishas, samurai, and common laborers in urban and rural landscapes.

Utagawa Kunisada, Picking up Shells on the Beach of Akashi (left sheet of triptych), 1853, L11.2022.20, Promised Gift of Charles Schoenknecht and Ward Paul

Traditional Ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking depended on an artist, a carver, a printer, and a publisher to create prints that were sold as single sheets or sometimes in books. Artists employed vertical and horizontal formats and occasionally would combine sheets to create a diptych or triptych that carried a story or scene across multiple pages. These scenes were increasingly a response to the interests and preferences of the general public. Artists drew from stories often popularized and adapted in dramatic performances at Kabuki theatres during the Edo period. This included important historical literary works such as The Tale of Genji, a classic 11th-century story about Prince Genji and his complex life in the Japanese court. Other narratives were drawn from well-known Japanese folklore or Buddhist legends, sometimes featuring supernatural creatures or spirits who interacted with notable heroes.

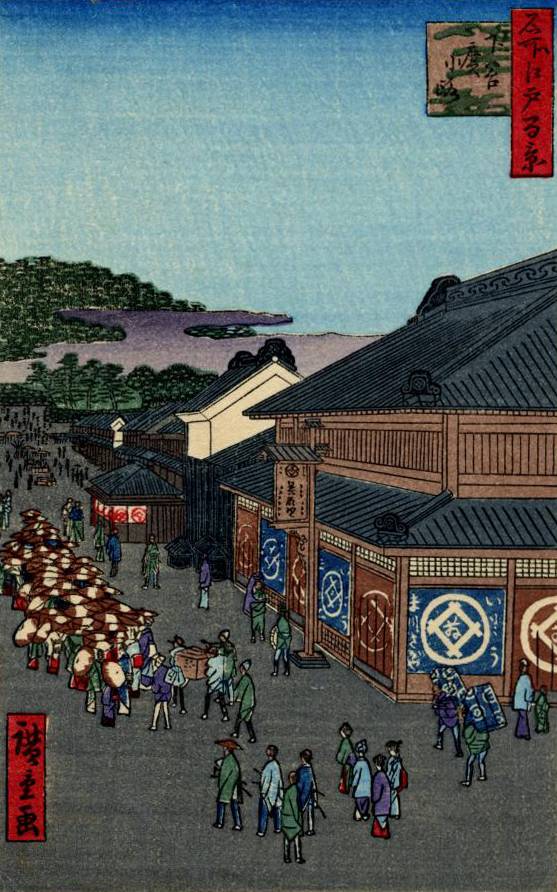

Narrative landscapes also became popular as artists interpreted famous sites through the lens of everyday experience. The development of the country’s thoroughfares, combined with illustrated travel literature, fueled the use of these routes by merchants, pilgrims, and sightseers alike. Artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige created compelling and sequential scenes, his most famous being the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido, a road linking the new capital Edo (now Tokyo) with the imperial one, Kyoto. These works combined clear outlines, flat colors, and unique perspectives, featuring the natural elements in all four seasons.

As modern life and printmaking techniques were introduced to Japan in the late 19th century, Western architecture, clothing, and customs emerged in their work. Despite these changes, artists continued to relay unique views and narratives ranging from the mundane to the mythical. Their work translated collective Japanese stories and experiences to print, creating compelling visions of the power of storytelling.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Shitaya Hirokoji: One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1856, L11.2022.473, Promised Gift of Charles Schoenknecht and Ward Paul

Location

October 20, 2023 - March 15, 2024

Kirkhof Wall Gallery

Kirkhof Center, Allendale Campus

1 Campus Drive

Allendale, MI 49401

For directions and parking information visit www.gvsu.edu/maps.

Contact

For special accommodation, please call:

(616) 331-3638

For exhibition details and media inquires, please email:

Joel Zwart, Curator of Exhibitions and Collections

[email protected]

For learning and engagement opportunities, please email [email protected].