STORY BY PEG WEST

PHOTOS BY KENDRA STANLEY-MILLS

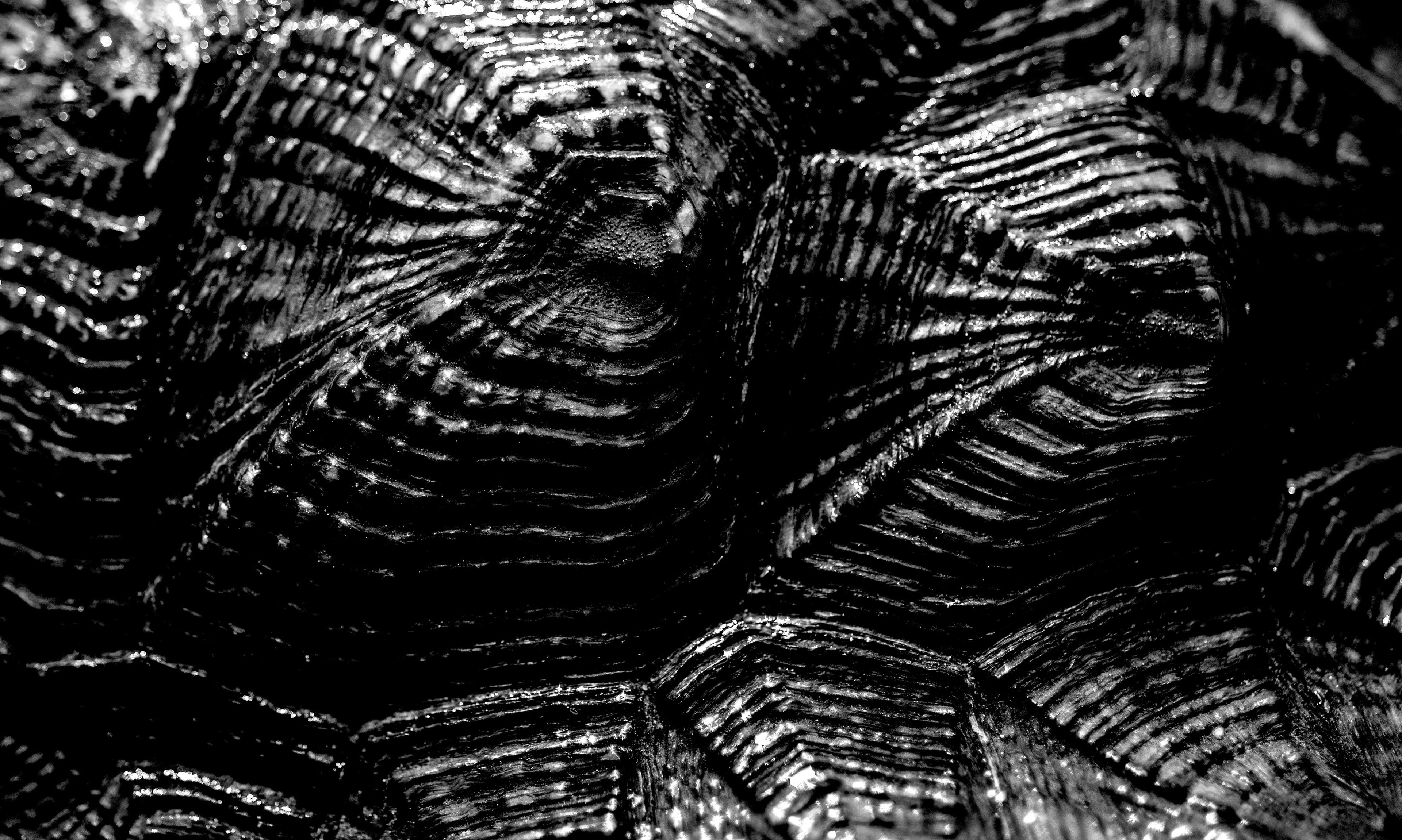

It was time to replace the special transmitter attached to the shell of a wood turtle who had been meandering along in her Manistee National Forest habitat when Grand Valley researchers homed in on her using telemetry and picked her up to provide the new equipment.

Erin Trimpe, biology graduate student, swaps out a transmitter on a wood turtle while doing research on wood turtles and raccoons in the Manistee National Forest.

Erin Trimpe, biology graduate student, swaps out a transmitter on a wood turtle while doing research on wood turtles and raccoons in the Manistee National Forest.

The student researchers created makeshift seats, such as overturned buckets, to encircle the turtle they had propped on a container for the shell work in the woods, while Jen Moore, professor of biology and interim assistant vice provost for The Graduate School, offered advice. They also took the opportunity to weigh, measure and record other data about the turtle.

The turtle — coined "Carmen Sandiego" by the students in a tribute to the beloved children's show, "Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?" — seemed unfazed by the interruption to her day. She calmly looked around and occasionally moved her legs in a swimming motion.

She was at home in her home. But this threatened species in Michigan also faces survival challenges from an ecosystem that is out of balance, leading to the overpopulation of a key predator for these turtles: raccoons.

And that is why raccoons in the area are also wearing transmitters placed by the GVSU researchers.

The challenge of abundant raccoons and dwindling turtle populations interacting is a familiar one to Moore, who has also worked on conservation efforts to help Eastern box turtles facing similar peril.

The efforts to help the Eastern box turtles involve a conversation technique that helps hatchlings, the most vulnerable to predation from that species, grow faster than they would in the wild. That effort gives young Eastern box turtles a chance to form the all-important hinge on their shells that come with age, allowing them to retreat into what Moore describes as nearly impenetrable “tanks.”

The wood turtles, however, cannot completely retreat into a shell. Their appendages are consistently exposed and therefore vulnerable to predation — even the adults. On top of that, adults don't start reproducing until they're around 15 years old, so they need a high survival rate to keep their population stable.

The aim of this multi-year research, which is done with support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and in collaboration with the U.S. Forest Service, is to better understand the particular threat that raccoons present to wood turtles, Moore said. Faculty members Paul Keenlance and Eric McCluskey are also collaborators.

"We're looking at the interactions of both of those species at the same time and in time and space," Moore said. "We're tracking the raccoons and we're tracking the turtles and we're trying to figure out where the turtles are most at risk when the raccoons and turtles are coming into contact and the sort of landscape features that might promote those negative interactions that we're trying to avoid."

Jen Moore, professor of biology and interim assistant vice provost for The Graduate School, center, laughs with graduate students as they do research on wood turtles and raccoons in the Manistee National Forest in late May.

Jen Moore, professor of biology and interim assistant vice provost for The Graduate School, center, laughs with graduate students as they do research on wood turtles and raccoons in the Manistee National Forest in late May.

A cadre of GVSU students is providing key field work and data collection for this project. They place transmitters on both species and use telemetry equipment to track their whereabouts and other behavioral information.

On the day they worked with Carmen the turtle, the students had earlier tracked raccoon movement. The nocturnal creatures were in their daytime slumber, and often pick different spots to sleep. But one raccoon, Jelly Roll — the raccoons have music-related monikers — was tracked to a usual sleeping spot, a tree with a notch many feet up.

One of these researchers, graduate student Erin Trimpe, came to Grand Valley for an advanced degree specifically because of this project. Trimpe, who had researched turtles before, welcomed the chance to work with wood turtles for the first time while also studying mammals.

"I hope we're able find areas where the wood turtles are most at risk and point out, 'OK, these environmental characteristics determine where they're more likely to be predated,'" said Trimpe, adding that the goal is to obtain "information that can truly inform some management decisions and some conservation efforts for the wood turtle that make a difference and can be potentially used in different areas, not just our site."

The project also offers critical training for Ava Whitlock, a recent wildlife biology graduate who will start work on a graduate degree in the fall. Whitlock is working as an assistant for this group while getting to know the Manistee National Forest for a separate graduate research project.

"I've worked with birds in the past, now working with another reptile and mammals, I'm really just trying to get a well-rounded experience and learn as much as I can," Whitlock said.

"It's our responsibility to make sure that we're good stewards of these ecosystems, and that sometimes means intervening to try and get them back to a more natural and functioning state."

Jen Moore, biology professor and interim assistant vice provost for The Graduate School

This type of research and potential intervention is necessary to help maintain a resilient ecosystem that has been thrown off kilter, largely by human behavior, Moore said.

Stable turtle populations are indicators of a healthy ecosystem, where the animals serve as both prey and predators and can be important for such things as seed dispersal and plant germination, Moore said.

Raccoons, of course, are also an important part of the ecosystem who also happen to adapt well to different environments. They particularly seem to thrive where there has been change by humans, Moore said.

"We can't really blame them for being good at what they do," Moore said. "But sometimes when the population numbers are overabundant or unnaturally high, it's because of the subsidized resources that humans have put on the landscape that allows them to eat more and reproduce more. That's where we get into trouble and we have species populations that are out of balance."

That adaptability, resourcefulness and intelligence makes raccoons fascinating to research, said graduate student Annah Huberts, who is focusing more on the raccoons in this project, such as studying their foraging, resting behaviors and even social interaction among the animals. Huberts hopes the data will help develop "meaningful conservation action and inform management to better encompass the intelligence and how prolific raccoons are."

"Maybe we can reduce the impact of raccoons and maybe uplift these turtles and other sensitive species," Huberts added.

The researchers will analyze the data and seek to come up with intervention solutions to help conserve the turtles. Moore said there are potential ways to manage the landscape to help turtle populations thrive, such as creating a nesting habitat closer to where they spend most of their time to minimize the need for risky travel that can lead to interactions with raccoons or motorists, another significant contributor to turtle mortality.

That human intervention is necessary, Moore said, because humans have already had an impact on natural systems.

"We have changed the way natural systems function, and that's OK because we're part of these ecosystems as well," Moore said. "But it's our responsibility to make sure that we're good stewards of these ecosystems, and that sometimes means intervening to try and get them back to a more natural and functioning state, and that's what we try and do in landscapes like this."