Solution

The Target Inquiry Model: Integrating a Theory of Change with a Theory of Action

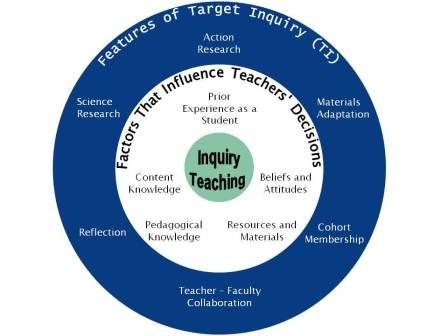

Theory of Change: Inquiry is the foundation of teaching and learning and at the center of the TI model (Figure 1). Rooted in social constructivism (Driver, 1995; Vygotsky, 1978), TI aims to influence factors which drive teachers' decision making about inquiry instruction (Figure 1, tier 2 in white) through transformative PD (Figure 1, tier 3 in blue).

The TI model is based on basic tenets from the literature which articulate the project's theory of change: (1) inquiry instructional strategies require a well-developed knowledge of content and pedagogy (Gess-Newsome, 1999; NRC, 1996); (2) changes in teachers' content knowledge, beliefs and attitudes, and pedagogical knowledge are required for instructional change (Anderson, 1996; Borko & Putnam, 1995; Loucks-Horsley & Stiegelbauer, 1991; Phelps & Lee, 2003; Shumba & Glass, 1994); and (3) effective PD addresses barriers to inquiry including lack of access to inquiry materials and assessments (Anderson, 2007; Caton, Brewer, & Brown, 2000; Straits & Wilke, 2002), curriculum constraints (Flick, Keys, Westbrook, Crawford, & Carnes, 1997; Keys & Bryan, 2001; Tretter, 2003), and inadequate in-service education (Anderson, 1996). These tenets comprise the second tier of the TI model (Figure 1, shown in white) and influence teachers' instructional decisions.

Theory of Action: With the central characteristics of high-quality PD such as duration, collective participation, active learning, coherence, and content-focus (Garet, et al., 2001) and critical features of transformative PD (Thompson & Zeuli, 1999) at its foundation, the TI model addresses the elements identified as critical for sustained instructional change by integrating three core experiences (research experiences for teachers [RET], materials adaptation [MA], and action research [AR]) with support features (reflection, cohort membership, and teacher-faculty collaboration), in alignment with NSES PD Standards. Support features embedded in the core experiences of TI provide opportunities for individual and co-construction of meaning. The TI model features are designed to improve inquiry instruction by influencing teachers' beliefs and attitudes, and enhancing content and pedagogical knowledge, thus empowering teachers to appropriately design or adapt instructional materials. Engaging teachers in TI, with over 500 hours of sustained and coherent PD, provides adequate time to facilitates and support lasting change to both instructional and classroom culture (Supovitz & Turner, 2000).

Although many teachers associate inquiry with the activities of research scientists, the underlying habits of mind by which one actively acquires new knowledge are the same for a scientist in a research laboratory, a student in a science classroom, or a teacher assessing student understanding (Llewellyn, 2005; AAAS, 1993). The 6-week RET allows teachers to further develop habits of mind central to inquiry such as curiosity, persistence, reflection, skepticism, and creativity while gaining firsthand experience in how scientific research is conducted. However, without a contemporary understanding of teaching and learning and clear connections to classroom practices, many teachers have difficulty translating the RET to instruction that promotes these same inquiry habits of mind (Blanchard, Southerland, & Granger, 2009; Gess-Newsome, 2001). During the RET teachers begin to examine and articulate the disconnect between the process of science inquiry, their beliefs about teaching and learning science, and their classroom practices, which Thompson and Zeuli (1999) have identified as critical for transformative PD programs. The other core experiences and supporting features of TI build upon the RET and address essential features of transformative PD by providing teachers with opportunities to resolve this disconnect, facilitating connections between the research laboratory and classroom, and supporting teachers in the development of new practices that effectively engage students in meaningful inquiry.

Teachers' instructional choices are heavily influenced by their beliefs about content and pedagogy (Jones & Carter, 2007; Keys & Bryan, 2001; Nespor, 1987; Pajares, 1992; Richardson, 1996). Thus, lasting instructional reform requires more than introducing teachers to new teaching methods and providing them with well designed materials. Implementation of well designed materials is often unsuccessful when teachers do not understand the rationale behind the curricula design, have no say in the adoption process, and are not personally invested in successful implementation (Cohen, 1995; McLaughlin, 1990; Roehrig & Kruse, 2005; Sprinthall, Reiman, & Thies-Sprinthall, 1996). Instead, teachers find ways to adapt new materials to fit into their current instructional practices, often undermining the intended benefits to student learning embedded in new materials. Teachers are more likely to implement and sustain successive, incremental changes as these allow them to improve their instructional practice by making important changes to aspects of their teaching while retaining effective elements of their instructional repertoire (Huberman, 1992; Knapp, 1997; Louis, Marks, & Kruse, 1996; McLaughlin, 1990). Thus, the MA component of the TI model which supports teachers' in designing or adapting classroom instructional materials that effectively use inquiry-based instructional methods, is crucial in ensuring that teachers are comfortable with and personally invested their implementation.

Finally, to produce sustainable instructional change, teachers' beliefs about teaching and learning must be examined and challenged. This requires teachers to continually reflect on the connections between their research experiences, their classroom practices, and the education literature. As teachers view learning from their classrooms as more important than learning from outside experts (Smylie, 1989), reflection that focuses on teaching and student learning is critical. Thus, another central piece of the TI model involves AR and reflection. The literature indicates that AR can positively sway teacher attitudes towards inquiry instruction, facilitate the implementation of innovative teaching methods or materials, and improve teaching and learning (Bencze & Hodson, 1999; Berlin, 1996; see review in Roth, 2007). This was seen in our pilot study at GVSU as several TI teachers identified student gains or challenges during their AR projects that compelled them to add more inquiry activities to their curriculum, conduct additional AR studies, and/or encourage others at their schools to implement TI developed materials. Moreover, through the yearlong AR project, teachers make connections between the inquiry process and teaching. Teachers once again engage in the inquiry process as they collect and analyze data to answer their questions about student learning and reflect on these findings to deepen their understanding of student learning and inform changes in their instructional approaches.