Longtermism: The Promise of Thinking Long-Term about Future Generations

A review of the book “What We Owe the Future” by William MacAskill (2022)

Nate Dugener and Bopi Biddanda, Annis Water Resources Institute, Grand Valley State University

A new book on Longtermism (long-term thinking) argues that the sooner this concept finds a space in our homes, classrooms and boardrooms, the better it is for us all – current and future generations of humans and the all life-supporting biosphere.

“Why should I care about future generations? What have they ever done for me?” – Groucho Marx (1890-1997).

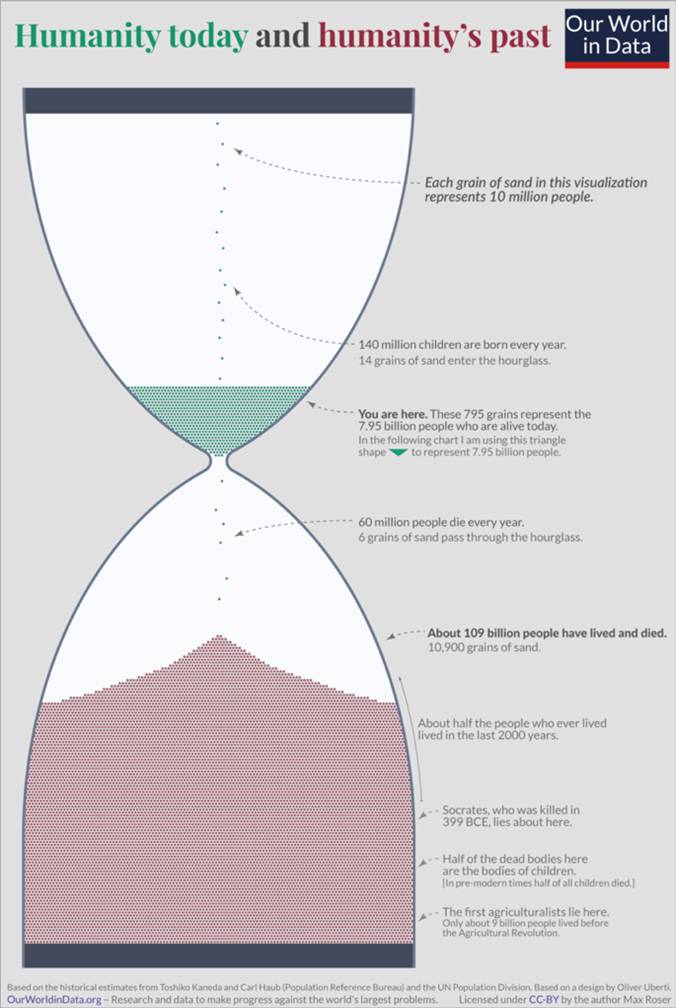

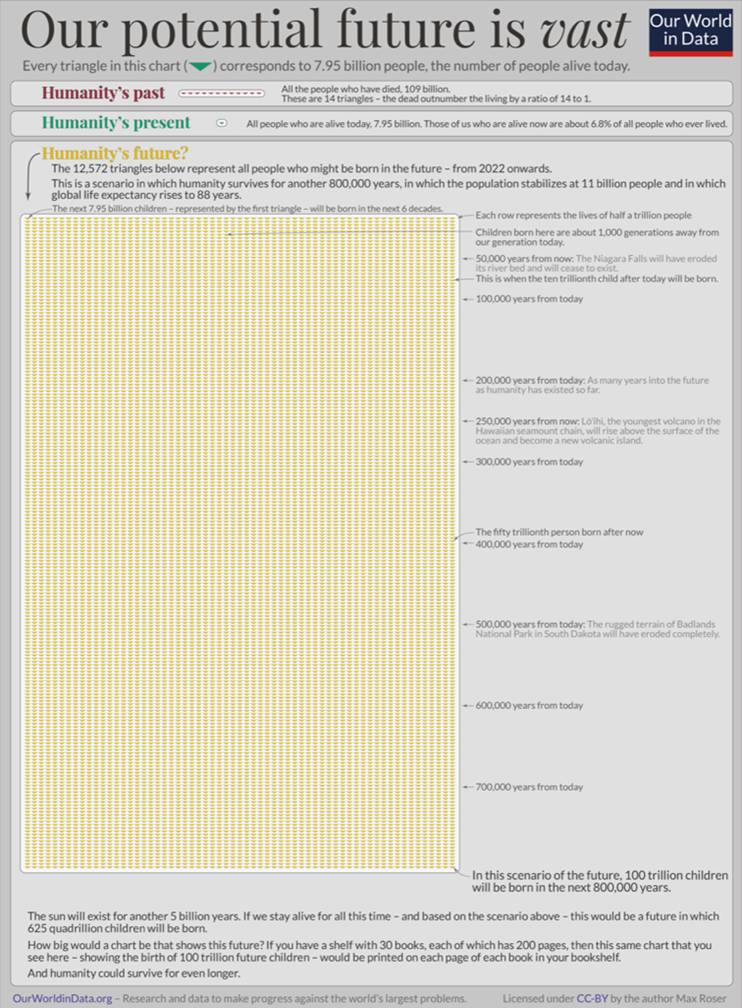

In a rapidly changing world, everyone wonders what the future of ourselves, our children and grandchildren will be like. Some may even stop to wonder what the very future of humanity on Earth may look like hundreds to thousands of years into the future. Admittedly, it is difficult to look into the distant future and imagine conditions and perspectives that future generations of humans will experience in one million or even one hundred years. However, barring a 6th extinction, it is possible that billions or even trillions of humans will live on our planet in the future – long after our time here is done. Do we, the present generation acting as stewards of the planet in the current Epoch, Anthropocene, owe anything to these potential future generations?

[1671156369].jpg)

Cover of the Book Under Review: “What We Owe the Future” by William MacAskill (Basic Books, New York, 2022, p. 333, ~$30). Prof. MacAskill is a professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford and is the co-founder of 2 nonprofits: Giving What We can and the Center for Effective Altruism.

Can thinking in the long term like this help us not only overcome our shorter term global challenges – but also ensure secure, healthy and rewarding lives for the coming generations? These philosophical yet practical considerations are at the forefront of the arguments addressed in this new book by William MacAskill. MacAskill examines the future of human existence in the face of many potential longterm threats such as climate change, artificial intelligence, threat of nuclear war, and engineered pandemics. For example, we can look to indigenous cultures around the world such as the Native American’s ideology, specifically the Iroquois Confederacy, of the seventh generation which is to ensure that the seventh generation from now will have adequate resources to maintain their culture. Should we strive to protect the future generations and their living world? Can this approach serve us to better our lives in the short-term even as we leave behind our home better than we found it for the coming generations?

The historical events that led up to our current existence on earth were shaped similarly to how we can shape the future conditions for generations to come. Although the thought behind this may not be easy, MacAskill provides a framework of significance, persistence, and contingency to prioritize future risks of humanity. Significance is examining the value of a given thing. Persistence is the length a given thing will exist. Contingency is if there is no action to affect the given thing, how long would it last. The framework helps to prioritize future concerns of climate change, artificial intelligence, and nuclear war based on the current and potential future state of affairs. In the words of MacAskill, this book is about “Longtermism – the idea that positively influencing the longterm future is a key moral priority of our time”. Within its pages, he makes the argument that “What we do now will affect untold numbers of future people. We need to act wisely”.

Conceptual Diagrams of Longtermism: Humanity today with reference to all the past lives lived (left image), and generations that will potentially come after us into the distant future (right image). Image Source: Max Roser - https://ourworldindata.org/longtermism, CC BY 4.0.

What We Owe the Future is broken down into five parts which explain longtermism, the future trajectory we could potentially find the human race drifting towards, the importance of safeguarding civilization against future risks, assessing which future risks we may encounter first, and considering the impact our current human population can create for the longterm. MacAskill effectively outlines longtermism by first engaging the reader into the importance of longtermism in today’s point of view. Throughout human history, the biggest changes in society have come in times of plasticity – a period of revolutionary change. A time period of plasticity occurs when ideologies can take the shape of many forms, but it provides a vehicle for acting in the best interests of the fate of humanity’s future conditions.

Across human history, civilization has been remarkably resilient. MacAskill mentions that maintaining plasticity multiple times throughout human history has reduced the chance of value lock-in and allowed for adaptive changing of morals and growth of societies. One example that MacAskill mentions is the plasticity during the Civil War which ultimately resolved in the freedom of slaves. If value lock-in or rigidity of values were to occur at the time of slavery, slaves may still exist around the world today. Further, MacAskill states the importance of safeguarding the humans from potential disasters such as engineered pathogens, artificial intelligence, nuclear war, and accelerating climate change. One major concern for MacAskill is the population of the earth after a potential collapse of some civilizations across the world due to climate change or exhaustion of resources. MacAskill argues that civilization would be able to reestablish regardless of the loss from catastrophic events given the survival of a small population in refugia somewhere. Regardless, MacAskill drives home the point that simply because of human resiliency up to this point, we shouldn’t assume that we could rebound from a nuclear war or excessive climate change.

MacAskill then dives into population ethics that are difficult to understand as described even as he and other major philosophers of our time cannot fully grasp population ethics of a future world. For example, do future people who are yet to come, have moral rights? However, virtual and anonymous future peoples may seem to us, it is all but certain that an incalculable number of them will likely come into this world. Here, new concepts such as “Principle of Intergenerational Equity” come into play where “each generation leaves its successor a planet that is in at least as good a condition as the last generation had inherited it”.

Although longtermism isn’t a topic most people are comfortable thinking about, the subject is necessary and relevant everywhere and in everyday activities. Longtermism sparks growth and innovation in many areas of human society to protect against irreversibly harmful events before they happen. So, what can we do to help safeguard the present civilization and also the disenfranchised future humans reduce their chances of experiencing an existential crisis? Introducing the subject of longtermism into our schools and into a variety of majors at the college level can inspire our generation to not only do what is best for the present, but also invest in protecting the future state of humanity and the unique life-support system around us.

MacAskill also makes the claim that sparking change almost always occurs in a movement, whether that being the civil rights movement or the woman’s suffrage movement and envisions a longtermism movement where we do more good for the current as well as the future world. Despite the light-hearted quip from Groucho Marx asking why we should bother about future generations, all of us living today will soon become the previous generation. Ultimately, a true measure of our current lives may be how useful ours will be to those who come after us. Afterall, we do care about the lives of dear ones who are thousands of miles away. So, we should be able to care about people thousands of years in the future as well. It is decidedly time for the rise of a Longtermism movement.

“To live is to be useful to others." – Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BC - 65 AD).

Additional References:

- Bajekal, Naina. 2022. How to do more good: A growing movement seeks to improve the world today – and for generations to come. TIME August 22-28, 2022.

- Ricard, Matthieu. 2015. Altruism: The power of compassion to change yourself and the world. Chapter 41. Altruism for the sake of Future Generations p. 616-689. Back Bay Books.

- Roser, Max. https://ourworldindata.org/longtermism, CC BY 4.0,

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116154119