Lower Grand River 319 Project - Grand River Beacon-Spring 2003

Articles from the Newsletter:

- The Lower Grand River Project is Underway!

- Did You Know?

- What is a Watershed?

- What is Nonpoint Source Pollution and What Does It Mean To Me?

- What in the World is a BMP?

- I Remember When...

The Lower Grand River Project is Underway!

Abigail Matzke, Annis Water Resources Institute

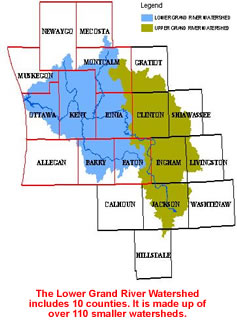

The Lower Grand River Watershed Project is going to result in the creation of a watershed management plan for the approximately 3,020 square miles of the Lower Grand River Watershed. This is made possible as a result of a 319 Nonpoint Source Watershed Planning Grant. The project started in early fall 2002 and will be completed in the fall of 2004.

Why a watershed management plan? To identify the sources, threats, and causes of nonpoint source pollution and propose ways to prevent the pollutants from entering waterways.

A 319 Nonpoint Source Watershed Management Plan will create a plan that builds on the success of the past. The Lower Grand River Watershed has many small rivers and streams that have been studied, and some already have their own nonpoint source plans. Now it is time to create a plan for the whole Lower Grand River Watershed to help focus human, financial, and technical resources.

A nonpoint source plan can improve water quality, habitat quality, and the quality of life in human communities. This plan will focus on nonpoint source pollutants such as sediment, thermal pollution, bacteria, and nutrients. To address some of these issues, small portions of the project will be studied in greater detail.

The watershed is a very large area, some of the smaller subwatersheds will become pilot projects and will be studied more in detail. Pilot projects are necessary because time is short and it is impossible to collect the many details that are necessary to characterize the entire Lower Grand River. Pilot projects are selected by their land use (urban or rural), water quality, public interest, and other factors. The idea being that each pilot project will be different from the others and thus cover a lot of different management scenarios. Using these pilot project watersheds and other completed watershed management plans, communities without nonpoint source plans for their streams and rivers can make their own.

How did this come about, you ask? For many years point source pollutants (sewer discharges, industrial discharges, etc.) have been the focus of community efforts in protecting water quality. All the hard work on point source discharge is paying off. Now is the time to focus on nonpoint source pollutants. Many of the communities in the Lower Grand River Watershed have pledged resources toward the completion of this project. Resources could be financial, labor, technical assistance, or equipment.

Please take the time to support your community's involvement with this project as it is protecting your environment. Check with your local unit of government to see if your community is involved with this project and if there is anything you can do to help.

Dan Wolz, Clean Water Plant, City of Wyoming

- The number one reason for the increase in life expectancy in the 20th century is chlorination of drinking water, because it eliminates bacteria and diseases in the water.

- The average daily flow in the Grand River is 2,440,000,000 gallons (2,8237 gallons/second).

- The Grand River watershed covers 5,572 square miles (10% of Michigan's total area).

- In 1972, only 36% of lakes and rivers were fishable and swimmable in the continental U.S.

- In 1994, 91% of lakes and 86% of rivers and streams were fishable and swimmable in the continental U.S.

Did you know that there are management plans being developed for both the Upper, Middle, and Lower Grand River Watersheds?

Did you know that since 1980 organic waste from industrial water pollution (a point source pollutant) has fallen by 46%, toxic organics by 99% and toxic metals by 98%?

Did you know the most common cause of pollution of streams, rivers and oceans is storm water (a nonpoint pollutant) running off from farms, paved areas, streets and yards?

Did you know that snowmelt runoff is responsible for 40% of annual water that flows into the Great Lakes? Without BMPs the snowmelt from parking lots and roads can damage waterways.

Jane Secord, Center for Environmental Study

A watershed is an area of land. But the definition doesn't stop there. It is an area of land which drains to a common point. In other words, all of the water that is under it AND all of the water that runs off of it drains to the same place, the same body of water.

Watersheds share plant and animal life, soil types and climates. They are defined in terms of their natural boundaries, rather than political ones. Because all water in a watershed eventually drains into the same body of water, everyone in the watershed is connected through the water we used for drinking, recreational activities and industries.

Watersheds come in all shapes and sizes, ranging in size from a few acres to thousands of square miles. Any landscape, be it rural or urban, is made up of many interconnected watersheds. The continental United States is divided into 18 major drainage basins, one of these being the Great Lakes Basin. The basins are made up of hundreds of smaller subwatersheds, such as the Lower Grand Watershed, which also contains many even smaller subwatersheds.

What is Nonpoint Source Pollution and What Does It Mean To Me?

Elizabeth Robins, Ionia County

We may not think about it much, but we've all seen the signs of nonpoint source pollution. Nonpoint source pollution (NPSP) is pollution that is difficult to trace back to a specific site/source. Nonpoint source pollutants include sediments, nutrients, pesticides, bacteria, and road salt. These pollutants can be detrimental to both surface and ground water.

Nutrient loading is an effect of NPSP when nutrients accumulate to levels, which exceed the need of the environment. Nutrient loading can cause weeds to choke out streams and ponds or an excess of nitrates in your drinking water. High nutrient levels often stem from failing septic systems, pet wastes, manure run-off, and over-fertilized lawns. Bacteria are another pollutant that is associated with these sources.

Another type of NPSP, sedimentation, occurs from wind erosion or runoff that strips soil particles off the land and deposits them in nearby waters. Sedimentation can disrupt fish habitat and spawning grounds. Wind erosion and run-off can also carry pesticides and road-salt, which can in turn pollute the groundwater and surface water which are the sources of your drinking water.

You can help counteract or lower the effects of NPSP by maintaining your septic systems, adopting conservative practices around the house (use less fertilizer, pesticides, etc.) and by participating in your local watershed group.

Patricia Pennell, West Michigan Environmental Action Council

Best Management Practices (BMPs) are structures, vegetation, and management techniques that protect resources and prevent pollution. Essentially, they solve environmental problems.

Why do we need BMPs?

Over the past 150 years, historically accepted management practices have resulted in polluted air, land, and waterways. Best Management Practices are used to help prevent and clean up this pollution.

How are they Used?

A BMP can be used to control storm water. A storm water BMP would handle rain on a developed site in a way that resembles what nature normally does with it. A retention basin could be used to hold rainfall or plants could be planted in a filter strip to filter rainwater. Also, limiting yard fertilizers is a storm water BMP because it helps keep this nutrient source from entering storm water that flows into rivers and streams.

Bonnie Shupe, Cannon Township

I remember when I was a child and we lived on the banks of the Rogue River near the small bridge that crosses Rogue River Drive. Each summer my dad and I would do our annual "float down the river" day. We would get a couple of air mattresses, put on our bathing suits, and let the current take us to West River Drive where my mother would pick us up. It always amazed me how long the journey would take compared to the short drive in the car.

Other memories of those days include the spring floods that would totally cover our lowland acreage. Our house was on a hill, so we didn't have to worry about a wet basement. Often the strength of the rushing waters would cause the small bridge to our island to be swept downstream. When the waters resided, we would have to "rescue" our bridge and put it back where it belonged. No matter how hard we tried to reinforce the structure, it seemed like each spring the waters would pick it up and toss it about again.

Also, there were days of fishing. I can remember my uncle getting strings of fish that he would clean and fry up. My friends and I searched for crayfish among the pebbled bottom of the stream.

At one point in my childhood, I can remember the river turning a sickening color, and emitting offensive odors. Soon we would find dead fish along the banks. Those were the days when the factories upstream were allowed to use the river as a drain with no thought to what damage was done downstream. Sometime between now and then, laws were changed to protect the river from direct discharge. Now our mission is to continue to protect it from the less obvious sources of pollution.