Interfaith Insight - 2020

Permanent link for "Remembering three who departed this past year" by Doug Kindschi on December 29, 2020

As we close the 2020 year, I remember three persons who in various

ways have influenced me and have passed from our world and from my

life this year.

Seymour Padnos I knew the longest, going back nearly 40 years. In

the 1980s, while serving as dean of science at Grand Valley State

University, he showed interest in the new engineering program that we

had established. He was CEO of the Louis Padnos Iron & Metal

Company, a company focused on recycling. It was founded by his father

who had emigrated from Russia as a teenager. Seymour Padnos had come

to me with a concern that most products are designed on the basis of

cost, function, and aesthetics, but with little thought on how the

product would be recycled after its serviceable life. Together we

came up with the plan to sponsor a national competition to encourage

engineering students to submit design plans that would enable

efficient recycling. Seymour and I traveled together to a number of

events when "Product Design for Recyclability Awards” were presented.

Padnos along with his wife Esther had made significant

contributions to Grand Valley toward the sciences and engineering. In

the 1990s the engineering school was named for them, and in 1996 the

Seymour and Esther Hall of Science was dedicated. Former President

Gerald Ford was a part of that event and both Seymour and Esther

Padnos were given honorary degrees.

Padnos was well-known for his love of sailing, and after the CEO

position was passed on to the next generation, I would often see him

while visiting my father in Florida during the university’s spring

break. On several occasions he would graciously have me join him for a

bit of sailing in the Palm Beach area where he wintered. After his

return to Michigan in late spring, I always looked forward to joining

him in Holland for lunch and enjoyable conversation. While our first

contacts were around science and engineering, I also got to know more

about his Jewish faith and his early involvement with

promoting interfaith understanding and acceptance. In 2018, the

Kaufman Institute was pleased to honor him with

our Interfaith Leadership Award.

His gentle spirit, inquiring mind, and his commitment to living

out his faith will always stay with me as I cherish this relationship

that ended this past July, just a few months before his 100th

birthday.

Luis Tomatis was born, educated, and received his medical

training in Argentina. He came to Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit for

further training in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in 1956, and

then to Grand Rapids in 1965 where he became a well-known and

respected heart surgeon for 30 years. I got to know him personally

following his retirement from medicine when he became the founding

president of the Van Andel Institute. In 1996, his first year as VAI

president, he attended the Padnos Hall of Science dedication and I

took him and his young grandson on a tour of the new building. Over

the years we became friends and I had the privilege of serving on one

of the Van Andel advisory boards. While I was dean of science I was

also able to sponsor him to receive an honorary Doctor of Science

degree at one of the university convocations.

Later, after he became the director of medical affairs for the

DeVos family, we continued our friendship and began meeting for lunch

nearly every month as he continued to work until his death this past

summer at age 92. We often talked about his medical work, science

interests, and commitment to building an outstanding medical community

in Grand Rapids. His impact on our community will be felt for decades

to come. In 2005, Luis founded the DeVos Medical Ethics Colloquy,

which sponsors a major forum twice yearly bringing noted speakers and

experts to Grand Rapids to explore significant issues in medical ethics.

As my own career moved to the arena of interfaith, I was pleased

to work with him on the colloquy board on planning these ethics

conferences. This coming February the Kaufman Interfaith Institute

will collaborate with the Colloquy on the topic of Religion and

Health. In my discussions with Dr. Tomatis, I also became more

appreciative of his deep Catholic faith as well as his interest and

appreciation of all faith communities.

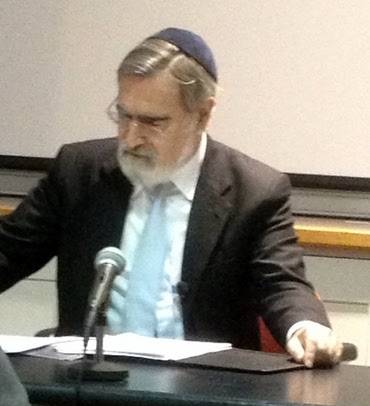

Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of Great Britain, died in

November this year at age 72 following a recent cancer diagnosis. His

impact on me was primarily from his writings, videos, and talks. On

one of my appointments at Cambridge University, I did, however, get to

meet him and hear him lecture. He was a wonderful speaker and his

videos are very inspiring, but it is his books that have had the

greatest impact on me and my thinking.

From my science interests and career, I found his book “The Great

Partnership: God, Science, and the Search for Meaning” very insightful

in my own decades of exploring the science and religion relationship.

His earlier book, “The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash

of Civilizations,” published in 2003, became a powerful response to

the alternative view following 9/11 that our global problem was

primarily a religious worldview clash. Readers of this column will

notice that I have quoted Sacks frequently and wrote about his latest

book, “Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times,” in an

Insight soon after learning of his untimely death.

In 2016 he received the Templeton Prize and, in his talk, noted

that many of the problems we face are in fact global, and yet we have

no effective functioning global organizations. He spoke of “a sense

among many throughout the world that the world is changing almost too

fast to bear, with no clear sense of direction, or purpose, or

meaning,” and asked that religions play an important role. The

world’s major religions are global and “are actually our most powerful

extant global organizations, much more so than any nation state.” He

continued by suggesting that they “provide what contemporary Western

societies do not provide, which is a sense of personal worth

regardless of wealth.” Furthermore, religions create and sustain a

sense of identity while also promoting strong communities. Finally, he

stated, “Religion is left at the end of the day as the single most

compelling answer to those three eternal questions: who am I, why am I

here, how then shall I live?”

Rabbi Sacks has been for me that clear voice reminding us that,

in spite of our differences, we are all created in God’s image, even

though -- or especially when -- the other is “not in my image, even

though his color, culture, class, and creed are different from mine.”

As I reflect on this past year with all of the problems we have

faced as a nation and in the whole world, I am thankful that these

three individuals have given me solace and direction. Their personal

presence will be missed but their influence will continue in the

coming years.

Permanent link for "Seeking the breath of God in today's world" by Lynette Sparks on December 22, 2020

[Note: For this Christmas week, our guest columnist is Lynette

Sparks, senior pastor at Grand Rapids’ Westminster Presbyterian

Church. She began her position this past June coming from the Third

Presbyterian Church in Rochester, NY. Before receiving her Master of

Divinity degree from Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, she

had received an MBA from Harvard Business School and had a career in business.

Today’s Insight is adapted from a sermon she gave on the Third

Sunday of Advent, which in the Christian liturgical year draws

passages from the Book of Isaiah that is shared in both Hebrew and

Christian Scriptures.]

Last week, a friend and colleague of mine posted a question on

his Facebook feed: What would you suggest as the word of 2020? Well,

as you can imagine, there were all sorts of one-word responses. Most

of them spoke to the brutal reality of the year. They included words

like alone, unprecedented, worse, exposed, ennui, unraveling,

reckoning, and traumatic. Not surprisingly, a few of the words offered

were even more frank, and probably better left unsaid. There were just

a few responses, however, that had a note of hope in them: opening,

unveiling, family, and transformational.

My first response was “breathless.” That could be the word

for 2020 that encapsulates so much of our world’s despair. Breathless,

as people around the world struggle with and die from COVID.

Breathless, as in George Floyd’s murder by a knee on his neck.

Breathless, as in waiting and waiting for election results to be

tallied and certified and recertified. Breathless, as in the feeling

you get when you experience a sudden shock or an unexpected,

earth-shattering loss. Even breathless as you try to juggle all of

your responsibilities — home, work, schooling, care-giving — and try

to somehow make it all work. It all leaves us breathless.

My second one-word response, however, is inspired by the

prophetic message from Isaiah — a message that expresses all for which

we long on our most breathless of days. And that word is “breath,” as

in the Hebrew noun “ruach” used throughout the Old Testament for the

Spirit of God. It is only divine breath that can transform our

breathless existence. It is only divine breath that has the creative

power to bring life.

Lisa Sharon Harper, author and columnist for Sojourners magazine,

writes about the Spirit of God moving over the waters in the Genesis

creation story: “The wind, the breath, the violent exhalation of God

moves over this surging mass of misery ... it’s as if God’s spirit ...

positions herself to confront the misery and destruction, the sorrow

and wickedness. She broods over it as if she is about to do battle

with the darkness. Her strategy for engagement is birth — new life.”

So, in light of the Spirit of God’s movement in creation, I

invite you to consider the words of the Hebrew prophet Isaiah:

The spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has

anointed me; he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to

bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and

release to the prisoners; to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor,

and the day of vindication of our God; to comfort all who mourn; to

provide for those who mourn in Zion — to give them a garland of

flowers instead of ashes, the oil of gladness instead of mourning,

the mantle of praise instead of a faint spirit. They will be called

oaks of righteousness, the planting of the Lord. ... They shall

build up the ancient ruins, they shall raise up the former

devastations; they shall repair the ruined cities. … For as the

earth brings forth its shoots, and as a garden causes what is sown

in it to spring up, so the Lord God will cause righteousness and

praise to spring up. (Isaiah 61:1-4, 11)

This is a creation story! It’s about breathing life into a world

breathless from so much destruction. This is about God’s animating

breath creating new life where even people of faith have hard time

imagining it’s possible.

The world needs the good news of God’s enlivening breath,

especially when we’re discouraged, and God longs to breathe it into

our lungs. Imagine the people of Judah hearing this message in their

discouragement and their frustration because their life wasn’t

anything like they expected. You see, they had gone through the

hardest of times. Once exiled, now they were unsuccessfully trying to

rebuild their destroyed community. It wasn’t going well. They wanted

to establish economic equality. They wanted to end the religious and

political divides that split their community. But their reality wasn’t

even close to what they’d envisioned.

The joyful news in Isaiah is that God longed to breathe life into

them with a salvation that was not only spiritual, but also material

and concrete and incarnational; one that included not just a promise

of life beyond this life, but one that embraced every aspect of life

in the here and now; a salvation that encompassed not just a

relationship between a single person and God, but one that restored

all of creation into unbroken community with one another. In other

words, salvation that looks like justice. The Spirit of God breathes

justice for all who are poor, heartbroken, mourning, and held captive.

The message itself offered the possibility to transform. By

hearing what God longed to do, those who were despairing could change

the way they viewed themselves and the way they acted toward others.

The message would replace their ashes with a festive garland of

sweet-smelling flowers, their sorrowful mourning with the fragrant oil

of gladness, their faint spirit with the joyful mantle of praise. New

creation was possible now – not just later. And new creation was

offered for all nations, not just Judah.

“As the earth brings forth its shoots, and as a garden causes

what is sown in it to spring up, so the Lord God will cause

righteousness and praise to spring up before all the nations.” (Isaiah

61:11) After a long and bleak winter, can’t you just smell the fresh,

spring-time soil? Can’t you just get a whiff of new blossoms?

Isaiah’s message offers the hope of new creation to us in our

breathless world. It invites us to inhale the breath of God deeply.

Receive the word of hope that oxygenates our souls, enriching them

with divine possibility. Smell the rich soil and the tender shoots

that spring forth.

And then, exhale the breath of God onto the breathless world

around you. For this joyful message of salvation also calls us to be

God’s agents of new creation, planting seeds of justice that grow into

God’s intentions for the world. Justice is God’s work of setting the

world right, and God is passionate about doing just that for all who

are weak, or broken, or exploited. God calls us to love justice as

much as God does.

Because even though we’re open to pursuing justice in the outside

world, sometimes we’re blind to the injustice we perpetuate among

ourselves. Seeing those places takes some careful work, introspection,

and courage. Especially around concerns for racial justice and

representation, are there cherished icons or practices or traditions

that we need to reexamine? Or do we hold back from seeking justice

because we mourn what we might lose for ourselves?

Can we imagine the new creation waiting to be born, as we deeply

inhale the breath of God? Can we imagine the joy of building up all

who are ruined and devastated? Can we imagine the joy of bringing

justice to all who are oppressed, brokenhearted, and held captive? Can

we imagine the joy? Justice and joy are not mutually exclusive. They

are both biblical, and they are both filled with creative possibility

— even the possibility of God’s animating breath filling the lungs of

a newborn, in a breathless city called Bethlehem.

Permanent link for "The holiday season during COVID" by Doug Kindschi on December 15, 2020

Yes, the holiday season is here, but different this year than any in memory. There are the increasing COVID cases and record numbers of deaths. Most celebration events are online, restaurants are closed, and even private meetings are discouraged given the rapid spread of the virus following Thanksgiving and the anticipated spike during the December holidays.

And yet there is good news with the beginning of the approved vaccinations taking place, even though many of us will have to wait months before they become widely available. It is not the time to let down our guard or for a few more months at least.

While the winter darkness joins with the dark immediate outlook on the health scene, it is also a time for the various religious communities to seek light.

This week the Jewish community celebrates Hanukkah, which began last Thursday evening and continues for eight days, culminating the evening of Friday, Dec. 18. The tradition goes back to the second century B.C.E. with the rededication of the Temple after it had been defiled by invaders. The menorah was lit but there was only enough oil for one day, and yet the flame continued for eight days. This miracle led to Hanukkah being called the Festival of Lights.

Hanukkah is not considered a major religious holiday and is not mentioned in the Torah. It has become, especially in America, more commercialized due to the commercialization of Christmas. It should also be noted that this year the first night of Hanukkah, Dec. 10, is also the International Day of Human Rights. Perhaps it should also be a reminder that just as the origin of Hanukkah was the re-establishment of the Jewish Temple following its capture, it should be the human right for all religious communities to worship in freedom.

Earlier this month, on Dec. 8, Buddhists of the Zen tradition celebrated Bodhi Day, the day Siddhartha Gautama experienced enlightenment and thereby became the Buddha. The Sanskrit term for enlightenment is Bodhi and expresses an internal coming of the light. Because Buddhism spread from India and Nepal 2,500 years ago, it was contextualized by the cultures that began to engage with it. As a result Buddhism in Tibet is somewhat different than Buddhism in Japan or Buddhism here in the U.S., and so there are often different days in the year that Bodhi Day is celebrated.

Buddhist homes will often have a ficus tree they decorate with beads, ornaments, and multi-colored lights similar to the way Christians decorate Christmas trees. Buddhism also strives toward the realization of interconnectedness of all beings, thus seeking to promote the deep responsibility to all.

As the days darken, more than a billion Hindus, Sikhs, and Jains have celebrated Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights. The word Diwali comes from the Sanskrit word deepavali, meaning "rows of lighted lamps."

Many of these celebrations occur near the Winter Solstice when in the Northern Hemisphere we experience the shortest day of light. It is of interest that this year on Dec. 14, one of the longest days of sunlight in the Southern Hemisphere, a total solar eclipse was visible in parts of Chile and Argentina. A partial eclipse was also seen in other locations of southern South America, southwest Africa, and in parts of Antarctica. It was a short time of darkness in the middle of one of the longest days for this part of the world as well.

Other religious holidays occur at other times of the year and not all religions use the same solar calendar as is common in the West. The Islamic Lunar Calendar is shorter than the solar calendar, and the religious holidays thus come approximately 11 days earlier each year than the previous year. Accordingly, Ramadan, the month of fasting from sunrise to sunset for Muslims, begins this year on April 13, about one week after the Christian celebration of Easter.

Fasting entails no eating or drinking, but more importantly it requires abstaining from impatience, anger, judgment and the plethora of bad deeds that might have been present throughout the year. It is a time to reset practices, clear thoughts, and work toward practicing all that is good and right. It is a time of reflection that could be compared to the Christian practice of Lent that occurs the 40 days prior to Easter. Ramadan ends with a major celebration for Muslims called Eid al-Fitr. The day starts with prayers followed by a lot of feasting and visiting with friends and family.

During this dark winter season, Christians also celebrate with light by lighting candles each of the four Sundays of Advent, and decorating with lights on Christmas trees and with other decorations. The victory of light over darkness also represents the victory of knowledge over ignorance and understanding over prejudice. Especially in this year when the darkness of the days is combined with the COVID threat of more deaths, we must also use it as a time for renewal and hope.

During these dark winter days, all religious communities need this time to celebrate a season of light. At this time of darkness in the world and in our nation where fear, health challenges, conflict and even violence threatens, let us come together seeking understanding and peace. Knowledge of other traditions and getting to know others who celebrate differently helps us come together as community. Interfaith understanding does not mean that all religions are the same or that the differences do not matter, but it does mean that we recognize our common humanity and pursue “peace on earth and goodwill to all.” Let this be our commitment.

Posted on Permanent link for "The holiday season during COVID" by Doug Kindschi on December 15, 2020.

Permanent link for "Is your God too small?" by Doug Kindschi on December 8, 2020

While growing up many decades ago, I don’t know if my God was too small, but certainly my church community was.

We were a very small denomination that broke away from the regular Methodist denomination back in the mid-1800s. I later learned that the issues then were social justice concerns such as abolition, ordination for women, and various lifestyle practices such as the use of alcohol and tobacco. Our group was opposed to slavery at that time but also opposed to the prohibition of women’s ordination. So I grew up with ordained women preachers in some churches, but also with a tightening of the prohibited lifestyle practices including not only alcohol and tobacco, but also dancing, movies, even playing cards. As we looked around, we didn’t see those same prohibitions being followed by other Christian groups, hence their lack of faithfulness would be punished in the next life. Our group was small and so also, we believed, would be the occupants of heaven. Yes, it was all very small.

As I grew older, went to college and then graduate school, my world became much bigger. The book, “Your God is Too Small,” published in 1952 by J.B. Phillips, an Anglican parish priest, got my attention and helped me see a bigger community as well as a much bigger concept of God. I got to know these so-called “regular Methodists” -- even marrying one -- spent time in Europe getting to know members of the “Evangelische Kirke” (the way the Lutheran church is known in Germany), and my world began to grow. I met so many devout and spiritual persons that I just couldn’t exclude from God’s grace.

As the Second Vatican Council opened up my understanding of the Catholic community my view expanded again. In the 1960s I recall attending an ecumenical service and standing next to a nun in full habit, singing together that famous Martin Luther hymn, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.” My world got bigger again, as did my understanding of God and the community of the faithful.

In graduate school my Old Testament professor put us in touch with a Jewish family who invited us to join them for the Seder meal at Passover. I realized that this was the meal Jesus celebrated with his disciples and became personally connected to the reality that Jesus and all his disciples were Jewish. I wondered, are they also a part of my larger understanding of the community of the faithful?

Meanwhile, undergraduate and doctoral study focused on mathematics and the sciences where my world again began to grow. We now know, thanks to the Hubble telescope, that there are over 100 billion galaxies like our own Milky Way galaxy. And yet, it was less than 100 years ago, in 1923, that Edwin Hubble’s research established that there were in fact galaxies other than our own. The appropriately named Hubble telescope has opened up our understanding to an enormously bigger universe than we could ever have imagined. Wow! Our God is not small and neither is God’s creation.

Now as I engage in the world of interfaith, my concepts and understanding keep getting bigger as does my understanding of God’s mercy. The breadth of God’s mercy is not a new concept in our religious history as we observe in our scriptures. The Jewish Scripture tells of Moses ascending Mount Sinai to receive the two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments. God addresses him saying, "The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness." (Exodus 34:6) The Psalms frequently acknowledge mercy and compassion, as in Psalm 145:8-9: “The Lord is gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. The Lord is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made.”

Likewise, in the Christian Scriptures God’s mercy and compassion are central, and when Jesus is approached it is often with the plea to have mercy. The Beatitudes affirm in Matthew 5:7, "Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy." The parable of the Prodigal Son exhibits both God's mercy and models the need for human mercy. Christian liturgy often includes the Kyrie eleison, “Lord have mercy.”

In Islam, mercy and compassion are frequently affirmed and “Most Merciful” is one of the names of God. Each chapter of the Quran (except one) begins with “In the Name of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy,” and the phrase “God is most forgiving and merciful” appears frequently in the chapter texts. In fact, the term mercy or merciful appears over 500 times in the Quran. One of the five pillars of Islam is showing mercy by giving alms to the poor.

As I have learned more about the various religions and their teachings, I have found my understanding of God keeps getting bigger as well as my understanding of God’s mercy. As I reflect on my earlier limited understanding of God and God’s mercy while growing up, I also recall a hymn that we sang that should have given me a hint of that which I would later learn. The text, written in 1862 by Frederick William Faber, has been set to nearly 20 tunes and appeared in over 800 hymnals. The hymn titled “There is a Wideness to God’s Mercy” includes the following verses:

There’s a wideness to God’s mercy,

Like the wideness of the sea.

There’s a kindness in God’s justice,

Which is more than liberty.

There is no place where earth’s sorrows

Are more felt than up in heaven.

There is no place where earth’s failings

Have such kindly judgement given.

For the love of God is broader

Than the measures of the mind,

And the heart of the Eternal

Is most wonderfully kind.

If our love were but more faithful,

We would gladly trust God’s Word;

And our lives reflect thanksgiving

For the goodness of our Lord.

As the prophet Micah taught, we should seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly. Walking humbly includes being open to a God who is bigger than our minds can measure, and whose mercy is wider than the sea.

Posted on Permanent link for "Is your God too small?" by Doug Kindschi on December 8, 2020.

Permanent link for "Are you OK? An important question for today" by Doug Kindschi on December 1, 2020

This past week we all found ways to celebrate Thanksgiving, either by

staying home seeking to avoid further COVID spread, or taking the

chance of travel in spite of the warnings of rapidly increasing cases

and deaths. Lately my influences have come from “across the pond,” the

term often used to discuss matters between the United Kingdom and the

United States. The recent obituary for Rabbi Jonathan Sacks in the

British journal, The Economist, reminded me again of his powerful

voice as we seek to respond to the question for our society, “Are we OK?”

The obituary described Rabbi Sacks’ growing concern about our

culture’s climate shift from a “we” to the “I” as follows: “Every year

the voices became more strident and extreme. Consumerism cried ‘I

want! I want!’ Individualism cried ‘Me! Me! My choices, my feelings!’

until even the iPhone and iPad he used all the time vexed him with

their ‘I, I, I.’ Society had become a cacophony of competing claims.

The world gave every sign of falling apart. Even religion, his

business, could be a megaphone of hate.”

The Economist noted that he was much more than an Orthodox rabbi;

he was also a moral philosopher who through his three dozen books,

many lectures, and radio and video messages had a much wider audience

both among the various religions as well as the secular community.

“A rabbi was, after all, a teacher,” the obit reminded us. As he

spoke to this broad audience, it noted, “He wanted to leave his mostly

secular listeners in no doubt that things were good or evil, true or

false, absolutely, and that moral relativism was the scourge of the

age.” The Economist concluded, “The world could be changed not by

force, but by ideas. … Every man and woman had a duty to care for

others, and thus to recreate the bonds that held society together. ‘I’

had to give way to ‘we’. Out of great crises — climate change,

coronavirus — that chance might come. Ideally religion could drive

this change, with the world’s faiths uniting. … In his last book, he

called for a shared morality: agreed norms of behaviour, mutual trust,

altruism, and a sense of ‘all-of-us-together.’ The liberty craved by

‘me’ could be sustained only by ‘us.’”

Another voice asking the important question is actually an

American, but now with British credentials: the Duchess of Sussex,

better known on this side as Meghan Markle, wife of Prince Harry. In a

very moving essay in last week’s New York Times titled, “The Losses We

Share,” she asks the question in the subtitle, “Perhaps the path to

healing begins with the three simple words: Are you OK?”

She discloses for the first time the loss she and Prince Harry

suffered from her miscarriage last summer. She also connected it to

the losses and pain that we have all felt this past year. She writes

about a journalist who, while she and Prince Harry were on tour in

South Africa the previous year, asked her, “Are you OK?” Duchess

Meghan notes that she is rarely asked that question, but realized that

the first step in healing is to ask clearly, “Are you OK?”

Given the challenges of this past year, she suggests it is the

question for us all, “Are we OK?” We have been brought to the

breaking point, she continues: “Loss and pain have plagued every one

of us in 2020, in moments both fraught and debilitating. We’ve heard

all the stories: A woman starts her day, as normal as any other, but

then receives a call that she’s lost her elderly mother to Covid-19. A

man wakes feeling fine, maybe a little sluggish, but nothing out of

the ordinary. He tests positive for the coronavirus and within weeks,

he — like hundreds of thousands of others — has died.”

Markle continues her litany of loss and pain by revisiting recent

tragedies. “A young woman named Breonna Taylor goes to sleep, just as

she’s done every night before, but she doesn’t live to see the morning

because a police raid turns horribly wrong. George Floyd leaves a

convenience store, not realizing he will take his last breath under

the weight of someone’s knee, and in his final moments, calls out for

his mom.”

But it is more than these vivid events that have filled our news

feeds; it is also the attack on truth itself. Yes, we have differing

opinions but now we can’t even agree on what is true. “We aren’t just

fighting over our opinions of facts,” she writes, “we are polarized

over whether the fact is, in fact, a fact.” We refuse to accept

science and the hard facts of the pandemic and what we must

collectively do to slow its spread. Markle connects her grieving the

loss of a child to now grieving the loss of our country’s shared

belief in what is true.

When asking that simple question, “Are you OK?” are we prepared

to actually listen to the person who is willing to share, to hear with

an open heart? This is the first step in the healing process for

individual grief as well as for our attempt to understand the

divisions in our society.

Going through this very different Thanksgiving season, Markle

urged that while “many of us separated from our loved ones, alone,

sick, scared, divided and perhaps struggling to find something,

anything, to be grateful for — let us commit to asking others, ‘Are

you OK?’ As much as we may disagree, as physically distanced as we may

be, the truth is that we are more connected than ever because of all

we have individually and collectively endured this year.”

I conclude by returning to another voice from the United Kingdom,

Rabbi Sacks, who has had great impact on my thinking. Just a few weeks

before his untimely death from cancer, his latest book, “Morality” was

released in the United States. In the epilogue he wrote for this

edition he asks, “What will be the shape of a post-Covid-19 world?

Will we use this unparalleled moment to reevaluate our priorities, or

will we strive to get back as quickly as possible to business as

usual? Will we have changed or merely endured?”

This can be a crisis that need not be wasted if it helps each of

us, as well as our collective democracy, rediscover the truths that we

are not alone, we need each other, and we must care for each other. If

we do we will be able to answer the question, “Are we OK?”

Permanent link for "Facing the crisis: Religious voices calling for solidarity" by Doug Kindschi on November 24, 2020

Note: Today’s Insight was first published in March of this year

as we first began to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, eight months later, we have reached over 250,000 deaths in our

country with deaths now over 1,000 per day. We are running this

Insight again with some minor changes as we seek to understand our

situation and responsibility from a religious perspective. It is

still my hope that it can bring us together.

Who would have guessed that it would take physical separation to

bring us together? That a microscopic virus would be the common enemy

that nations would come together to defeat?

It is not the first time in history that there has been a

worldwide health challenge that threatened the survival of millions.

The first documented major plague began in 542 CE (the Common Era)

during the reign of Byzantine emperor Justinian I. At its

height,10,000 people were dying each day in Constantinople (today’s

Istanbul, Turkey). The infamous Black Death in the 14th century

killed an estimated 25 million people in Europe, almost a third of the

continent’s population. About 100 years ago, the so-called Spanish flu

pandemic of 1918 led to over 20 million deaths.

Thanks to modern science and modern medicine we have a much

better understanding of how these pandemic crises work, and we know

more about how to respond and reduce spread of the virus and mitigate

deaths. While we must physically separate (social distancing), we

have worldwide media, excellent communication, and even social media

to keep the world informed of the situation and what must be done in response.

The religious communities also have a major role in responding to

the crisis. It is good to note some of the historical responses as

well. Julian of Norwich, an English mystic from the Middle Ages, gave

her famous response to the plague that was ravishing Europe: “All

shall be well, and all shall be well, and every manner of thing shall

be well.” A religious faith helps us put things in perspective.

The famous 20th century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr helped put

things in perspective in his book “The Irony of American History.” He

wrote, “Modern man lacks the humility to accept the fact that the

whole drama of history is enacted in a frame of meaning too large for

human comprehension or management.” Yes, there are things that happen

not only beyond our control, but often beyond our ability to make meaningful.

Niebuhr had served as a pastor in Detroit for 13 years, from 1915

to 1928, before his 30-year career at Union Theological Seminary as

professor of Applied Christianity. He called Americans to a sense of

humility about “the virtue, wisdom and power available to us for the

resolution of history’s perplexities.” We are drawn into historical

situations where “the paradise of our domestic security is suspended

in a hell of global insecurity.” While he was writing about a

different crisis, the Cold War of the mid-20th Century, he might have

been describing the crisis we face today when the entire globe shares

the insecurity and fear of the pandemic.

But Niebuhr would want us to act. He is also famous for his

Serenity Prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I

cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom

to know the difference.” Yes, this is a time for action in ways we

can change the course of the coronavirus, wisdom to know what to do,

and acceptance of what is beyond our control.

Another famous religious leader and Protestant reformer, Martin

Luther, also combined action with acceptance. Back in 1527, a deadly

plague hit Martin Luther’s town of Wittenberg. Some were calling for

mere acceptance of what was happening as God’s will about which they

could do nothing. In a lengthy letter to fellow pastor and friend Dr.

John Hess, he addressed the question, “Whether One Should Flee from A

Deadly Plague.”

Luther writes: “I shall ask God to mercifully to protect us. Then

I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine and take

it. I shall avoid places and persons where my presence is not needed

in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance inflict and

pollute others and so cause their death as a result of my

negligence.” Sounds like advice coming from the CDC nearly 500 years later.

Richard Rohr, widely recognized ecumenical teacher, Christian

mystic, and Franciscan monk, sees our current situation as an

opportunity for our coming together. He wrote, “If God wanted us to

experience global solidarity, I can’t think of a better way. We all

have access to this suffering, and it bypasses race, gender, religion,

and nation.” He calls it a “highly teachable moment.”

Rabbi Sacks, former chief rabbi of Great Britain, also saw hope

in our situation. In an interview on BBC he said, “We’re coming

through this feeling a much stronger sense of identification with

others, a much stronger commitment to helping others. This, in a

tragic way, is probably the lesson we needed as a nation and as a world.”

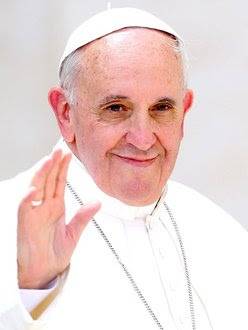

In a similar way Pope Francis calls us together saying, “We do

not have to make a distinction between believers and nonbelievers;

let’s go to the root: humanity. Before God, we are all his children.”

He continued this call for solidarity in reminding us that “humankind

is one community… there will no longer be ‘the other,’ but rather ‘us.”

Archbishop Cardinal Cupich asked Catholic parishes in Chicago to

ring their church bells five times a day, as a means of calling all to

unite in prayer during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Our hope is that people

will have the experience of being united in prayer, especially at a

time when we are isolated,” he said. “We invite our neighbors

throughout the archdiocese to join in pausing and lifting up in prayer

all affected, so they will know of our support.”

So, with Cardinal Cupich, and also with our Muslim neighbors who

are called to prayer five times each day, let us ring the bells or say

a prayer to bring us together. Let us pray for the heroes in the

health community who risk their lives each day to preserve our health.

Let us pray for those challenged by the virus and for all mankind,

that we might learn from this crisis that we are more alike than

different -- and that we need each other.

Permanent link for "Remembering Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks" by Doug Kindschi on November 17, 2020

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of Great Britain, died

on Nov. 7, at age 72, following a cancer diagnosis the previous

month. He had been treated for cancer twice in previous years.

Author of over 20 books and hundreds of broadcasts and talks,

Rabbi Sacks was considered a major leader in religious thought not

only for Judaism, but also for the inclusivity of

all religious perspectives, as we seek to learn from difference as

well as from a deep appreciation of one’s own faith heritage.

His influence on me has been particularly profound as I followed

his daily postings and read many of his books. In a quick review of

my previous Insights, I find over 25 columns have referred to and

quoted him, including six during this current year. It was my

privilege to have met him during my first extended stay at Cambridge

University in 2013, and to hear him lecture and then interact with the

former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, who was in his first

year as Master of Magdalene College at Cambridge.

Sacks had studied philosophy at Cambridge in the 1960s and at the

age of 19 took what he called his “Greyhound tour” of America seeking

both academic and spiritual direction. It was on this trip that two

rabbis in New York City greatly influenced him. One he describes as

having challenged him to think; the other challenged him to lead. So

he returned to England to devote himself to study and leadership

through further study to become a rabbi. He was ordained in 1976 and

later completed his Ph.D. in philosophy at the University of London.

Following a series of leadership positions at several prominent

Orthodox synagogues in London, he was named chief rabbi in 1991, a

position he held for 22 years.

Rabbi Sacks was widely recognized in religious, secular, and

political communities for his writing and leadership, especially as he

interpreted the Jewish vision in ways faithful to its tradition but

open to the insights from other faith traditions.

Rabbi Sacks was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 2005 and given a

life peerage that brought him to the House of Lords in 2009. He was

close to former Prime Minister Tony Blair, who said of the rabbi that

he “had the rarest of gifts — expressing complex ideas in the simplest

of terms,” and called him “a man of huge intellectual stature but with

the warmest human spirit.”

Sacks’ latest book, published earlier this year, “Morality:

Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times,” introduces what he calls

the “Cultural Climate Change." It is a change that threatens

democracy itself. He writes that within the past half century we have

experienced a shift from “We” to “I” with results that could destroy

our society and our ability to work together. It has resulted in a

loss of trust in public institutions as well as its leaders. It led to

extremism in our politics, lack of shared knowledge, and an inability

to address major issues like global change and income disparity.

Identity politics has abandoned its focus on the nation as a whole

while replacing it with what is best for my group, for those who share

my identity.

While the emphasis on the “I” would seem to bring more individual

happiness, the opposite has happened. Drug overdoses and suicide rates

have actually tripled in the past 20 years. Income disparity has

dramatically increased and, for example, in California, home to

thriving hi-tech and entertainment industries, homelessness is a major problem.

Sacks describes three basic systems required for a functioning

society: the economy, about the creation and distribution of wealth;

the state, about the legitimization and distribution of power; and a

moral understanding as “the voice of society … the common good that

limits and directs our pursuits of private gain.” The cultural climate

shift away from the “We” to the “I” has led to a breakdown of our

shared morality, leading to the loss of caring for others or even

thinking about the other.

“Morality achieves something almost miraculous, and fundamental

to human achievement and liberty,” Sacks writes. “It creates trust. It

means that to the extent that we belong to the same moral community,

we can work together without constantly being on guard against

violence, betrayal, exploitation, or deception. The stronger the bonds

of community, the more powerful the force of trust, and the more we

can achieve together.”

Morality broadens our perspective and helps us see that we are a

part of something bigger than ourselves. Without a shared morality and

with everyone in it for themselves, the rich and the strong will tend

to use their power to exploit the system for their own benefit.

Rabbi Sacks is calling for a renewal of our shared sense of

morality in order to humanize the forces for wealth and power. He

writes, “When we move from the politics of ‘Me’ to the politics of

‘Us,’ we rediscover those life-transforming, counterintuitive truths:

that a nation is strong when it cares for the weak, that it becomes

rich when it cares for the poor, that it becomes invulnerable when it

cares about the vulnerable." It is a call for the future of

democracy and a call to “recover that sense of shared morality that

binds us to one another in a bond of mutual compassion and care.”

Sacks’ book was written before the COVID pandemic had begun and

was published in the United Kingdom before the global impact was

known. The American publication came out later, for which he added an

epilogue in which he asks, what will be the result of this worldwide

crisis? Will we reevaluate our priorities or could it even drive us

further away from a shared morality? As one who has always lived in

hope, he expresses his hope that we will emerge with a stronger sense

of human solidarity, a keener sense of human vulnerability, and a

stronger sense of our social responsibility. A return from the “I” to

the “We.”

This is indeed a message for our nation and for the world. I am

so sad that, while we will have his rich store of writings, speeches,

and videos, we will not have his personal presence to continue to lead

and inspire us in our quest for healing and wholeness. Let us take to

heart his message and come together as a stronger “We.”

Posted on Permanent link for "Remembering Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks" by Doug Kindschi on November 17, 2020.

Permanent link for "What can faith teach us about healing division?" by Doug Kindschi on November 10, 2020

“To help our nation heal in the wake of the 2020 election, I think the most important thing we can do is to recognize that democracy is a sacred project.” So wrote Eboo Patel, founder and president of Interfaith Youth Core.

In a brief post-election reflection, Patel shared his experience of 20 years of interfaith training for emerging leaders of how religious commitment can profoundly impact our civic life. He discusses three ways this perspective can help us begin the healing process.

First, we must, as every major religion teaches, see “every human being as sacred.” In a democracy every person has the right to vote and to be heard. It means welcoming the diverse contributions of all citizens. It is why Abraham Lincoln, addressing a divided nation in his first inaugural address, urged that we not see each other as enemies but as friends, and called all citizens to pursue the “better angels of our nature.”

Second, Patel sees democracy, especially at this time, as sacred in the call for repentance. The bitterness and division that is so prevalent invites, no, requires a time of repentance. He referred to the highly respected civil rights activist and congressman John Lewis. When segregationists like George Wallace sought his forgiveness, Lewis responded that as a Christian he was called to forgive.

The third impact, Patel writes, is “seeing democracy as a sacred project in that it generates processes for redemption and reconciliation.” He recalls the response of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who did not talk of anger or revenge following the Montgomery bus boycott, but said “The end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the beloved community.”

Patel concludes his reflection urging “that as we move on from the advocacy for particular political sides during an election season, we have to shift to the idea of reconciliation.”

The Rev. Wes Granberg-Michaelson is well-known in this area from his days as former head of the Reformed Church in America. In an article he wrote a couple of years ago in the journal Oneing, he also sees politics as a sacred project that must be seen through the eyes of faith. He wrote:

“Transformative change in politics depends so much on having a clear view of the desired end … For the person of faith, that vision finds its roots in God’s intended and preferred future for the world ... a world made whole, with people living in a beloved community, where no one is despised or forgotten, peace reigns, and the goodness of God’s creation is treasured and protected as a gift.” He continues by pointing out that we often have it backwards and begin with politics, and then try to fit our religion into our political goals. He writes, “We start with the accepted parameters of political debate and, whether we find ourselves on the left or the right, we use religion to justify and bolster our existing commitments.”

David French, a Harvard-educated lawyer, worked for many years defending religious liberty and free speech on campuses throughout the country. He was a staff writer for the conservative magazine the National Review, and recently became a writer and senior editor of the conservative news outlet The Dispatch. As an evangelical Christian active in politics, he also writes and speaks from his faith commitment as he addresses political issues facing our country.

In a recent chapel talk at Biola University in California, he raised the warning that political identity is replacing faith in our current environment. Honest concern about issues has been replaced with anger. The message, he warns, is “Be afraid, be angry,” and it is coming from both sides. In such a polarized society he urges that on whatever side you find yourself, seek out the reasonable voices on the other side, not necessarily the loudest or most extreme. In this way you have the opportunity to learn something rather than just accelerate the division. He also recommends modeling the values you affirm. If you want a civil society, then be civil to those with whom you disagree.

In the concluding chapter of his book “Divided We Fall: America's Secession Threat and How to Restore Our Nation,” French quotes the prophet Micah from the Hebrew Bible: “What does the Lord require, but to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with God.” (Micah 6:8) For French, putting his faith first, this call is an imperative for our political actions as well. He writes that “there is no solution to our national crisis absent those three cardinal virtues.”

In our polarized battles, each side fights for what it believes is right and just. In fact, it is this conviction of the rightness of our position that often accelerates the division. But French argues that we must go beyond this justice commitment to the qualities of mercy and humility. He writes, “Mercy is the quality we display when we are, in fact, right and our opponents are wrong. We treat them not with contempt but with compassion. In the aftermath of political victory, we seek reconciliation.” We remember Abraham Lincoln’s words from his second inaugural address, “With malice towards none; with charity … to bind up the nation’s wounds.”

Finally, humility is required to “remind us that we are not perfect. Indeed, we are often wrong and will ourselves need mercy.” French reminds us of the apostle Paul who recognized that we know the truth only in part and that “we see through a glass darkly.”

In our interfaith efforts we seek to begin with our faith commitments as we engage with those of other faith traditions who believe differently. We may not agree, just as we may not agree in the political arena, but we seek to understand and be respectful as we engage with others. This is in no way a dilution of our faith, but an acting out of that faith as we treat others with respect -- even though, and especially when, we differ in our beliefs and even in our politics.

Let our faith and its teachings lead us as we seek to heal division.

[email protected]

Note: I was saddened to read this past weekend of the death of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi for the United Kingdom, following his recent cancer diagnosis. He has been so influential for me through his talks, books, and daily posts. He has been the topic for many of my insights and I have quoted him often.

Permanent link for "After the election; One thing I know for sure" by Doug Kindschi on November 3, 2020

What will you know when you read this that I don’t know while writing

this week’s Insight? Will we know the results of the election, or

will there still be counting going on and perhaps even legal

challenges being made?

Whatever you know, whatever the results, or lack of results, I

believe I already know one thing – we will have a lot of work ahead to

heal the divisions and polarization that have occupied our public

discourse. And religion can help us heal, or can make things worse.

A report recently released by the Brookings Institution in

Washington dealt with this challenge. The 48-page report, “A Time to

Heal, A Time to Build,” provides recommendations on such topics

as religious freedom, pluralism, civil society partnerships, and the

role of faith in foreign and domestic policy. It was written by two

highly respected scholars, both senior fellows at the Brookings

Institution, Melissa Rogers and E. J. Dionne.

Rogers is a visiting professor at Wake Forest University Divinity

School and previously served as the executive director of the White

House Office of Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships. She also

served as executive director of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public

Life and general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee

for Religious Liberty. E.J. Dionne, Jr. is, in addition to his

position at the Brookings Institution, a syndicated columnist for the

Washington Post and university professor in the Foundations of

Democracy and Culture at Georgetown University.

The report recognized that religion in our public arena “will be

a matter of debate, dialogue, and disagreement for as long as we

remain a free and democratic republic. Americans have been arguing

with each other over the merits of particular faiths, the existence of

God, and the meaning of their scriptures from the inception of our

nation. They have also engaged each other over the merits of religion

itself — whether it is primarily a force for progress or regression,

whether it is more unifying or divisive.”

They note that it is fundamental to a free society that there

will be legitimate differences of opinion and clashes of interest.

These differences, especially over issues of justice, can lead to

anger, which can be productive as we struggle with the right course of

action to be taken. But they can also be nonproductive as mistrust

becomes toxic. Some have described it as a “cold civil war, which

implies the possibility of violence.”

Religion is a part of our division even within the

same religious traditions and reading the same scriptures. Such

divisions contribute to larger numbers of people, especially the

young, fleeing from any regular religious identification.

Furthermore, religious identities often merge with political

identities, making the combination more dangerous. The authors cite

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s observation that religion “is not to be the

master or the servant of the state, but the conscience of the state.”

They urge that we “acknowledge that the weaponization of such

divisions for political purposes is dangerous to the nation’s

long-term stability.” We must also respect the views and commitments

of our fellow citizens across religious divides, they assert, and

“that their views and concerns are being taken into account, even when

their policy preferences are not enacted into law.” The report

continues asking us all to recognize and take seriously the many

wonderful contributions that religious groups make toward solving

problems and building community in our civil society.

The two authors come from different perspectives, one “a Baptist

committed to religious freedom and church-state separation. The other

is a columnist, an academic, and a Catholic who writes from a broadly

liberal or social democratic perspective.” They both acknowledge that

they identify with the social justice and civil rights teaching of

their respective traditions, and also embrace a commitment to

pluralism and openness.

They both believe “that it is possible to find wider agreement on

the proper relationship between church and state, and government

and faith-based organizations — and to get good public work done in

the process.” While they recognize church-state differences will

persist (as they have from the beginning of our nation), “those

differences can be narrowed, principled compromises can be forged, and

the work of lifting up the least among us can be carried out and

celebrated across our lines of division.”

The report sees “a commitment that vindicates the rights

of religious and racial minorities, of immigrants and refugees. It

stands against the proliferation of hate crimes against Jews, Muslims,

Sikhs, Black Americans” and other minorities. It is a commitment,

they write, that “honors the equal dignity of every American. It is

the only approach that can restore unity to a deeply divided nation.”

Religion can be a cause of societal tensions and strife. But it

can also be a constructive force in conflict resolution and play an

important role in economic development. Religious institutions have

often been vital providers of education and health care. Their feeding

programs, homeless shelters, and support at times of crises provide

immense social capital in our country as well as throughout the world.

Those of us committed to interfaith efforts have also practiced

the skill of dialogue with others whose beliefs are different from our

own deeply held commitments, but in such a way that leads to

understanding and respect. Let us take the same attitude to the

healing of the political differences facing America.

As we take our role in healing the polarizations in our nation,

let us use our religious commitments to bring resolution to conflict,

not to fan the flames of division. Let us be the “conscience of the

state,” not seeking the power of the state to carry out our own ideas

in ways that deny the religious rights of other citizens. Let it be

our mission to heal the divisions, seeking understanding and peace as

we go forward.

Permanent link for "Religious principles in voting and choosing leaders" by Doug Kindschi on October 27, 2020

Can our religious traditions help us in voting? In America we are accustomed to separation of church and state. In response to the question of paying taxes to a secular government, Jesus’ famous response was, “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” (Matthew 22:21)

Of course voting was not a consideration in his day, nor was that the case in the early days of most religions. And yet, nearly every religious tradition says something about what we should look for in our leaders and in our relationship to government. I inquired of my friends and persons involved in our interfaith understanding work to learn more about what their traditions teach.

In the early Hindu tradition, most societies were autocratic, but as early as the fifth century B.C.E. there were republics established with representative assemblies. A prayer was recited by members gathered: “We pray for a spirit of unity; may we discuss and resolve all issues amicably. May we reflect on all matters (of state) without rancor. May we distribute all resources to all stakeholders equitably. May we accept our share with humility.” (Rig Veda X.19.12) Modern India is the world’s largest democracy, with a 67% voter turnout.

The Buddha, living in roughly fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E., witnessed rulers who governed unfairly and unjustly, oppressing, persecuting, and putting themselves and their personal desires above the people they ruled. This troubled the Buddha deeply. In the Jataka text, the Buddha offered a teaching on the “Ten Duties of a King” that in modern terms would be duties of the government or president. With these 10 qualities the Buddha describes what one who leads a people should embody:

1. Generosity

2. A high moral character

3. Willingness to sacrifice everything for the good of the people

4. Honesty and integrity

5. Kindness and gentleness

6. Austerity in habits

7. Freedom from hatred, ill-will, enmity

8. Commitment to non-violence

9. Patience

10. Non-obstruction of the will of the people

The Jewish Talmud records one of the rabbis saying, “One should not appoint a leader for a community without consulting the community.” Even when God tells Moses whom he should appoint for a task in building the temple, according to this rabbi, God responds, “Even so, go and ask the people.” From this, one can conclude that voting is a religious obligation, a commandment that we participate in selecting our leaders.

The story is told of the Orthodox rabbi, Rav Avraham Karelitz, who was born in Belarus and lived his final 20 years in Israel. On election day he is said to have asked a man if he had voted yet. The man replied that he hadn’t because he didn’t have the money for the voting tax. The rabbi asked him if he had a pair of tefillin – the black leather boxes containing verses from the Torah that are to be worn by Orthodox men when they do their morning prayers. The man responded “Of course.” Rav Karelitz then said, “Go sell your tefillin to pay the tax and vote,” adding that he could borrow the tefillin to pray but the voting could only be done by that man on that day.

For Islam, the Qur’an directs that decisions should be conducted by mutual consultation and that honesty is required in all that one does. It is one’s duty not only to do what is right, but also to stand up and correct leaders if they are not doing or saying what is right.

The Baha’i community emphasizes the unity of mankind and of religion. Candidates should be evaluated based on the reputations of their service to humanity, their honesty, their integrity, their promotion of the equality of women and men, their promotion of universal education for all, and finally their promotion of the elimination of racism and other prejudices.

Jews and Christians share the scriptures known as the Tanakh or Old Testament. In it are many passages related to what one should look for in a leader.

Even when the Israelites were taken captive in Babylon, the Lord spoke to them through the words of the prophet Jeremiah, saying “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.” (Jeremiah 29:7) Referring to this passage, Bishop Craig Alan Satterlee of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America wrote:

“If God would have Israel pray for Babylon, where they were exiled, how much more would God have us pray for the United States of America, where we are privileged to live? The separation of church and state is a doctrine aimed at protecting religion from government interference. It is not an excuse that relieves people of faith from fulfilling our responsibility as citizens. So, as we approach Election Day … I ask you to do two things in addition to praying for the welfare of your city, our state, and our nation.”

“First, to seek the welfare of the city, state, and nation, vote. Make your plan. Vote in a way that is best for you. But vote.”

“Second, to seek the welfare of the city, sacrifice.” He continued by reflecting on a documentary that he viewed on what was happening on the home front during World War II, and noted the way Americans sacrificed for the sake of our nation. He continued, “We refuse to wear masks and keep social distance. We complain that we can’t get into our church buildings, sing songs, and drink coffee . . . We are unwilling or unable to sacrifice.”

He concluded with the reminder from Jeremiah and this charge: “Seek the welfare of the city, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare. Pray. Vote. Stay home. Keep social distance. Wear a mask. Sacrifice. Please.”

We enjoy in our country this wonderful privilege of choosing our leaders. Whatever our religious background and position on the issues, we can reflect, pray, and act in ways that are true to those principles and vote. It is our sacred duty.