The Art of the People: Contemporary Anishinaabe Artists

GVSU Performing Arts Center Gallery, Allendale Campus

January 11, 2021 - February 26, 2021

The Art of the People: Contemporary Anishinaabe Artists features artworks by nationally recognized and early career Native American artists that combine cultural traditions and imagery with contemporary sensibilities and themes. Organized by the Muskegon Museum of Art and the Grand Valley State University Art Gallery with guest curator Jason Quigno (Anishinaabe), this invitational show appears concurrently at the MMA and GVSU. Incorporating sculpture, painting, ceramics, beadwork, mixed media, and photography, the exhibition explores how these artists express their experiences in both traditional and nontraditional media, techniques, and subject matter. Through representational and abstract imagery and design the artists address issues of craft, history, identity, social justice, and popular culture. By exploring and celebrating their past, these artists define who they are today.

The Anishinaabeg Peoples have inhabited the Great Lakes area of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and sections of Canada for thousands of years. Anishinaabeg, which translates to “People Whence Lowered” or “the Good Humans,” encompasses several tribes that share similar languages and customs, including the Ojibwe, Bodawatami, Odawa, Salteaux, and Chippewa. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Anishinaabeg were a woodland people, living with the land and seasons. They drew all of their food, shelter, and tools and implements from the earth, lakes, and rivers that surrounded them. While most contemporary Anishinaabeg no longer live with the land, they remain a spiritual people tied closely to nature and surrounding cultural beliefs.

Early artmaking arose directly from the need to craft tools from wood and stone and vessels from black ash, birch, and cedar. As these objects, both practical and ceremonial, were fabricated, they were embellished with woodland designs and motifs – flowers, vines, leaves, and animals – often to signify a name or clan. This knowledge of craft and design was passed down to each new generation, which in turn adapted and innovated to their own circumstances and resources. Today, artists continue to work in the traditional media of basketry, stone, and beadwork, while others have moved into painting, photography, filmmaking, and sculpture. Whether through traditional or modern materials, the Anishinaabeg are still telling stories that carry knowledge to future generations.

The exhibiting artists were selected for their ongoing use of traditional techniques, materials, and imagery and for the ways in which their art shares the enduring stories of their culture. Many of the works on display tie directly to inherited methods of crafting and design, though with modern innovations and visual experiments unique to the artist. Others blend traditional imagery and design into contemporary art-making disciplines, revealing a different kind of continuity.

The Art of the People is an opportunity for the viewer to explore these varied points of view and discover the traditions that inspire them, bringing greater awareness and understanding of Anishinaabeg culture.

- Jason Quigno, Guest Curator

Land Acknowledgment

The GVSU Art Gallery would like to recognize the People of the Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples on whose land we are gathered. The Three Fires People are indigenous to this land which means that this is their ancestral territory. Every university is built on stolen, native land. We are guests on their land and one way to practice right relations is to develop genuine ways to acknowledge the histories and traditions of the people who originated here first, who are still here, and who tend to the land always. As we make this land acknowledgment, we know it is but an important first step, and that there are many more that we need to take when we decide to engage in the important work of social justice.

We pledge to:

1) provide indigenous artists with the platform to share their talents, artwork, and stories

2) appropriately collect, exhibit, and care for indigenous-made artwork and objects

3) create an environment where the history and traditions of artists indigenous to this area can be recognized and celebrated

For more information on the purpose and intent of land acknowledgments, see Northwestern University's site.

About the Curator

Jason Quigno

Anishinaabe, Mukwa Ndodem

Contemporary Stone Sculptor from the Great Lakes

Anishinaabe artist Jason Quigno was born in 1975 in Alma, Michigan. Jason works in in a variety of stone – granite, basalt, marble, limestone, and alabaster – transforming raw blocks into flowing forms. His work has garnered significant recognition and awards and he has completed numerous public commissions for communities and institutions around Michigan.

Q&A with Jason Quigno

About the Artists

Multiple artists within the exhibition work in traditional ways but with today’s sensibilities, adapting contemporary art-making to their cultural practice. Adam Avery and Summer Peters work in the media of beadwork, a decorative art form that is a defining characteristic of Native American art and identity. Beadwork likely grew from earlier quillwork, where dyed porcupine quills were used to adorn clothing and other fabric and leather goods. With the arrival of European traders and settlers, small beads and fine needles became available and the art form flourished. Avery adapts traditional floral motifs in his work, adorning such objects as top hats, sashes, purses, and bags. Peters brings markedly contemporary imagery into her beaded pieces, rendering portraits and pop culture and comic-inspired pieces alongside more unusual objects such as beadwork bikinis.

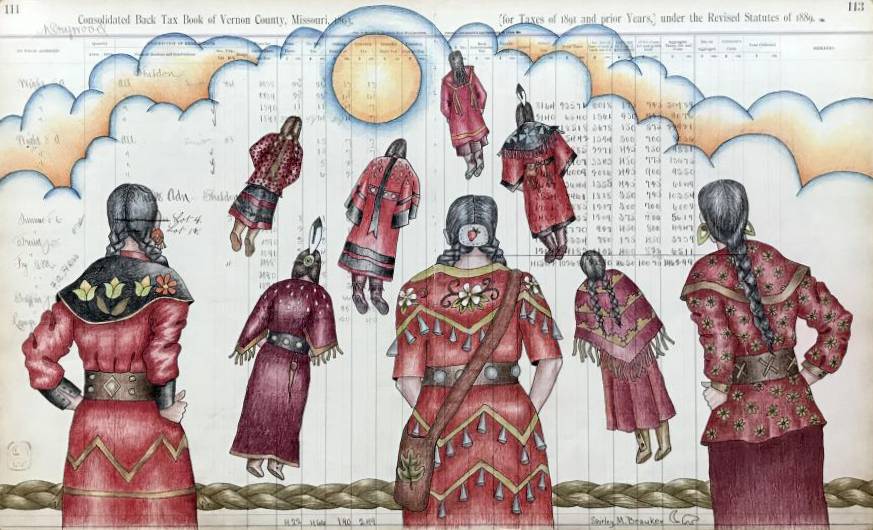

Shirley Brauker continues the tradition of ledger art, paintings of geometric patterns and narrative events that emphasize foreground objects over sparse, even empty backgrounds. The term “ledger art” comes from the use of ledger books by Plains Indians beginning the 19th century and Brauker utilizes this traditional material to address contemporary issues and narratives. She also works extensively with ceramics, telling new stories and incorporating various cultural motifs into functional and decorative objects.

How did you get interested in creating art?

I started out of necessity, making things for myself and family,

and from there it just evolved.

Talk about your own art training. Where/how did you learn your craft?

Everything I know and do has been handed down by elders. I

learned watching my grandparents, aunts, uncles, and my older brother.

Also, for the last several years, I have mentored with Ronald J.

Paquin, Mackinaw Band.

Who are your biggest influences?

My grandmother was one of my first big influences. She was always

making something; she was a black ash basket weaver, beadwork artist,

and a great baker. Growing up I spent a great deal of time watching

and working with my older brother, Chad. He is a natural born artist

and can work in any medium.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative practice?

Throughout my life many things have influenced my experience, the

greatest was when I met Lisa Kennedy, who has pushed me to focus more

on my art and supports me at every opportunity.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

I am most proud of is my Mishiikinh (Turtle) top hat, this is the

first piece of art that I have held on to for myself.

How has your career developed?

My career started when others saw the regalia pieces I would make

for my family, others would approach me to make pieces of regalia for

them and it grew from there.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

What I enjoy most as an artist is meeting so many people while

participating in an art show or market; I make another friend. Also,

I enjoy teaching, working with students, and it’s a great experience

sharing knowledge with others.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

The hardest part of being an artist is selling pieces, it feels

like you are letting a piece of yourself go and that’s a challenge

after putting so much time and energy into a creation.

Do you have any desired outcomes that you want the viewers to

come away with after engaging with your work?

I want people to come away with an appreciation for Indigenous

art, especially Ojibwe Woodland art.

How does tradition and identity inform your work?

Tradition and identity inform all of my work, is everything to

me, it is my life. I spend a majority of time doing my part to keep

traditional art alive and continue to learn and add more skills to

carry on and share with the next generation.

How does your work comment on current social or political issues?

The focus of my art centers around beauty and happiness. I’m

probably unusual in that I don’t focus on political or social issues.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I’m a full-time artist, always working on some form of

traditional art and sometimes that means making black ash baskets and

birch bark canoes, though more often it is beadwork.

What are some of the greatest challenges you face in making

your work?

The most challenging issue in making my art is harvesting scarce

resources like black ash trees because they have been decimated by the

emerald ash bore beetle. Also, finding birch trees large enough to

make a full-size canoe can be difficult too.

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I’m looking forward to more opportunities to create.

How did you get interested in creating art?

I have always been interested in art. I remember playing in mud

puddle clay at the age of 5 and feeling the magic. Then, years later

in my first college ceramic class, I experienced that same magic again

and said I wanted to do that forever; and I have.

Where/how did you learn your craft? Who helped you along the way?

I learned pottery from my college mentor, Dr. Jay Shurtliff. His

teaching and encouragement have led me to this place in my life. I

will forever be grateful for his faith in me. Education has always

been very important to me. I received both my Bachelor of Fine Arts

and Masters Degrees from Central Michigan University. I was also

awarded an Honorary PhD from CMU after I presented the Commencement

Keynote Address to the graduating class of 2015.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative process?

One of my most important influences came to me in a dream. I

dreamed I created a pottery jar that was cut all the way through,

leaving empty spaces between the turtles that were drawn around the

neck. I made that pot the next time I was in the studio. It was very

primitive, but has developed into the intricately carved pieces that

have become my trademark in the pottery world.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

It would be difficult for me to pick which art work is my

favorite or even one that I am most proud of. They are all like my

children and all of them are expressions of emotions or events that

have influenced their creation. Most of my pots tell stories. In

fact, I have started printing mini books that I bind by hand to let

others keep the stories fresh after they leave me. Many of the

stories come from cultural teachings while others have deep personal

meanings that are transferred into the surface of the clay through my

carvings. I believe these pieces will help educate the public and

keep these stories alive for future generations.

How has your career developed?

My career has gone from simple student exhibits at CMU to selling

in Native American Art Galleries and Markets across the country. I

have many pieces in private collections, museums, and large

corporations. Some of these include: The Smithsonian Institute,

Disney World, Honda Corporation, Sugar Diabetes Foundation, U.S.

Embassy, Eiteljorg Museum, Ziibiwing Cultural Center, Central Michigan

University, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, and the Institute of

American Indian Art Santa Fe.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

I thoroughly enjoy the hours I get to spend doing what I love. I

like interpreting my vision to others within my art. I like teaching

others the techniques and guiding people along the path of

creativity. I especially love passing this gift down to my family and

grandkids. It lets me realize that my legacy will live on.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

My biggest challenges come from organizing time for creating the

art, doing paperwork, writing to galleries and clients, and filling

out applications for art markets, fellowships, and grants. It is all

part of being an artist, so that thought keeps me going.

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

I believe that a culture can best be understood by their art. The

underlying stories that accompany the creations can tell the viewers a

lot about who created it but can also make the viewers understand

things about themselves. How they react to the visual aspects, the

feelings they get from the piece. When people look at my art, they

often have feelings that come to the surface. Sometimes it is a simple

smile, sometimes a tear. I want them to see my work from a new

perspective and enjoy it. They can look at it with a technical eye as

well as an emotional eye.

How do tradition and identity inform your work?

I create my work centered around Nature and my Native American

heritage. I use Woodland designs and legends as well as personal

experiences as the basis for my work. Each piece is a reflection of

my relationship with the world I live in.

How does your work comment on current social or political issues?

I have made several pieces that depict social issues of today.

My “Missing and Murdered” pots and ledger drawings are focused on this

current event. I have tried to bring attention to this through my art.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I work as many hours a day as I can. I am sure it is full time

occupation but the old saying “do what you love and you will never

have to work another day in your life” is so true. It doesn’t seem

like work when I’m in the studio. I love it, and it gives me such a

feeling of accomplishment and fulfillment. I am truly blessed to be

able to do this every day.

What are some of the most significant challenges you face in

doing your work?

Some of the challenges I have are keeping inventory moving

forward. Many of my pieces are very time consuming and I have to

budget my creative time. I also have to make sure my equipment is

running properly. I have to depend on my kiln and it is an expensive

item to fix or repair.

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I want viewers to see the immense talent that the Anishinaabe

people have. Many of us started out as kitchen table artists and have

come a long way. We have pushed forward through many difficulties and

adversities, but we have prevailed with beautiful works that tell of

our struggles and accomplishments along the way.

Basketmaker Kelly Church comes from a generational line of Black Ash weavers. Her practice preserves the traditional means of making with Black ash splints (layers of wood split from the rings) while also innovating with her use of nontraditional materials including vinyl blinds, metals, ribbon, and photographs. An expression of her contemporary artistry, this innovation is also made necessary by the environmental devastation caused by the emerald ash borer and the seemingly inevitable extinction of the black ash tree. Le’Ana Asher’s paintings showcase traditional Anishinaabe regalia (dance and ceremonial costuming), a celebration of enduring cultural practices now thriving once again after being banned by the U.S. Government for over a century.

Green Egg: Saving Traditions

Kelly Church

Black ash, sweetgrass, copper, dye

Collection of the Gun Lake Tribe

[1610048167].jpg)

Buffalo Shield Medicine

Le'Ana Asher

Oil on Canvas

How did you get interested in creating art?

My mother and my father were both artists. My father did drawings

and made many items from the fibers of the forest or deer he hunted.

My mom did all kinds of art and was my 4-H art teacher for many years.

I have always been encouraged by both to pursue my art career. They

both made me who I am today.

Where/how did you learn your craft? Who helped you along the

way?

I learned how to harvest, process, and weave baskets from my

father Bill Church and cousin John Pigeon. They each took me under

their wing and taught me everything I know today.

Who are your biggest influences?

I come from the largest extended black ash basket making family

in Michigan. While there are fewer of us that still practice these

skills, the knowledge is known and held by many in my family. Black

ash basket making traditions existed before this country did. My

biggest influences are my dad and John Pigeon, who have encouraged me

and taught me to pass on the traditions to the next generations.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative process?

My art comes from my heart. It is my life experiences that I

create from and for and the stories from our past that we carry on.

Many of my pieces will speak of the Emerald ash borer and its effect

on our traditions, or why Pipeline #5 needs to be removed to protect

the very lives of future generations. I consider myself an artist and activist.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

All works are important to me so I have no favorites.

How has your career developed?

My career began as a painter and sculptor at the Institute of

American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I received my AFA from

there and went on to receive my BFA from the University of Michigan in

Painting and Sculpture. It was while taking care of my grandparents

that I began my journey with black ash basket making. My grandfather

always wanted to thank someone for helping with the lawn or food and

used to say, “I want to make that person a basket.” It was his way of

showing someone how much he appreciated them. So I went to my Dad one

day and told him Grandpa wanted to give away thank you baskets, and

asked if he could show me how. We were in a car in minutes, off to

find a good basket tree, and that is the day this life journey began.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

I love working for myself and setting my own hours and days best.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist? It can be

challenging in between sales, or now during a pandemic when we are not

able to travel and show art in person. Though we have adapted and are

still adapting as humans do. We are showing virtually - I have

internet for the first time and a website to sell work.

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

I hope that viewers will see my work and begin to think of all of

the beautiful forests and waterways that we have in Michigan and

consider what Michigan would be like without them. If we do not see

our Great Lakes as Life giving and Life saving for our generation and

all future generations we may not have enough fresh water for all. If

we do not have water, we will not have forests either, or the animals

that live in our forests. Money should NEVER come before LIFE.

How do tradition and identity inform your work?

The traditional teachings that have been passed onto me by my

father and cousin are the beginning and basis for my work. I begin

each piece by practicing traditions from thousands of years ago, to

tell a story about my life today in the contemporary forms and voices

of my experiences. It is a combination of our past and our present.

The history of our past should never be forgotten.

How does your work comment on current social or political

issues?

My work speaks about current issues such as removing Pipeline #5

from Lake Michigan, or the demise of our ash trees due to an invasive

pest the Emerald ash borer. Currently I have been making masks with

various messages. A mask is such a small sacrifice to make to save

lives, yet it has become a political symbol. While some people are

gasping for air while others literally take their breath away by

putting a knee on the neck, there are those who say they can’t breathe

because they have to wear a mask, having really no idea what

struggling to breathe really is.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I am a full-time artist.

What are some of the most significant challenges you face in

doing your work?

The biggest challenge is finding good basket black ash trees as

they are decimated by the Emerald ash borer, and being able to collect

seeds for future generations.

How did you get interested in creating art?

I was the kid that carried around sketchbooks and doodled on all

my schoolwork. In second grade, the "art ladies" would come

into the art class with posters borrowed from the public library.

They would feature the life and career of famous artists such as Van

Gogh, Diego Rivera, and Georgia O'Keeffe. Discovering famous art and

learning about the artist behind it was my favorite part of school. I

then realized that being an artist was not just for famous people; it

was a real profession. From that moment on, I decided I would be a

professional artist when I grew up.

Where/how did you learn your craft? Who helped you along the way?

I was surrounded by creative matriarchs in my family, continually

sewing, making beaded jewelry, and crafting. These women encouraged me

to create and make things and to take pride in my Ojibwe culture. I

remember taking all the drawing and art classes my school had to offer

in my primary and secondary education. I stood out a little as no one

else in my family was interested in painting or drawing. In 1999, I

earned my BFA from Eastern Michigan University in painting and

drawing. I am a first-generation University college graduate.

Who are your biggest influences?

My biggest art influences are the famous artists Diego Rivera,

D.C. Cannon, and Sargent. My maternal grandmother was also a

significant influence; she taught me beading on looms, hand-beading

necklaces, earrings, and other arts and crafts. When I was 18 years

old, about to enter college, unsure what I was doing with my life, my

mother gifted me my late father's table easel. I had never known he

was a painter until then. It wasn't until years later I realized I

might be continuing what he started. I still have his easel in my home studio.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative process?

Love and loss have shaped a lot of who I am and what I do. I lost

several close family members at a very early age, most notably my

father. Without them in my life, I lost my sense of cultural and

spiritual identity. As I grew older, I realized they were the

knowledge keepers of our traditions, language, stories, and more. I

create art to continue my ancestors' legacy, culture, traditions, and

tribal identity.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

The oil painting titled "Aunt Becky" is a piece I

created were everything I had been working on over the years seemed to

come together: my style, my techniques, my color palette, and my voice.

How has your career developed?

After earning my art degree, I had a lot of false starts and

stops building my budding art business. I experimented with lots of

mediums and techniques. I was not fully dedicated to my art, didn’t

know where or what I was doing, or where to go next. Then I got

married and had children and found it hard to maintain a budding art

career and a family work-life balance. For many years my family came

first and my art took a back seat. During that time, I continued to

play and experiment artistically; I refined my oil painting skills and

made paintings for my collection and an occasional commission or two.

Around 2017, newly divorced, I renewed my studio art practice and

dedicated my time to creating a new body of work, entering shows,

marketing, and selling my art, all while being a single parent.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

Sharing my art with the viewer and seeing them connect to

something I created is the most rewarding experience. Personally

speaking, painting is my prayer, meditation, and my language. When I

paint, I get immersed in what I'm doing; I lose all sense of space and

time. On the flip side, I find when I'm not creating art I can feel

moody, depressed, and disconnected. I believe art is one of the best

tools to heal both the creator and the viewer.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

Being an artist is not for the faint of heart. Creating things

take grit, dedication, and a willingness to make lots of terrible

looking art. Staying committed to something when there is no

inevitable outcome is both an emotional and spiritual journey. Then

there is the business side of being an artist: marketing, promoting,

and managing one's art is all equally time-consuming and full of uncertainty.

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

I like the viewer to be pulled in and feel the figure's emotion,

whether it is sadness, happiness, or something else altogether. I hope

the brushstrokes, colors, and design are why the viewer stays for a

while or enjoys the painting for a lifetime.

How do tradition and identity inform your work?

My paintings reflect on how I see and experience our diverse

indigenous cultures and traditions. How we identify as contemporary

people and how we thrive to this day. Regalia is an essential aspect

of our way of life, and my paintings highlight the patterns, symbols,

and colors of our indigenous communities. I'm profoundly grateful and

honored to continue the tribal legacy of my people with my art.

How does your work comment on current social or political issues?

Not too long ago it was illegal to practice our traditions, to

dress in regalia, to pray, to sing, and to dance. My art subtly

references that we Anishinaabe people are still here; we are not only

survivors of genocide; we live and thrive today. I illustrate the

indigenous figures as contemporary people with traditional stories.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I am a full-time artist and a full-time single mother. The juggle

of work-life balance is real but worth every moment.

What are some of the most significant challenges you face in

doing your work?

COVID has presented me with considerable challenges, from

creating new art to sharing, exhibiting, and selling. The global

pandemic has exposed some old and new inequalities in art, health,

economic structures, education, communities, and raising families.

There is no playbook to being an artist or a parent. Doing both well

at the same time is my biggest challenge.

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I would love to see this show or ones like it travel to other

museums. I want the Anishinaabe artists to network and exhibit more

often together as a community. I believe it is vital we share our

story and our way of life. I want to see female indigenous artists get

more opportunities.

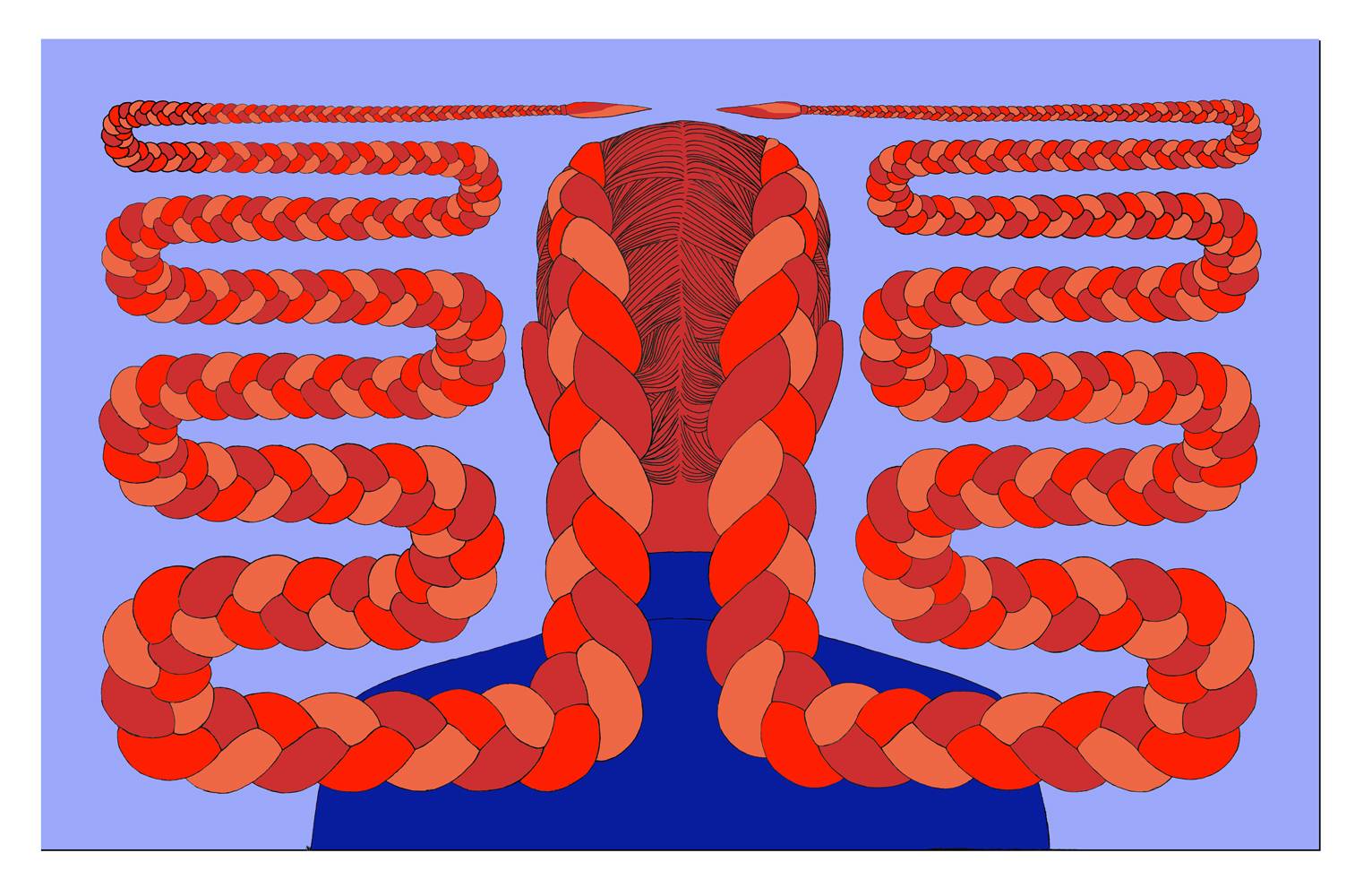

Robin Waynee comes from a family of artists and brings her cultural motifs into jewelry making, creating nontraditional pieces that convey a clear sense of Native American identity. Wally Dion’s work uses a similar approach, adopting timeless motifs into thoroughly modern pieces in a host of media, including quilts made from circuit boards, painted portraits of contemporary Anishinaabe, mixed media sculptures, and intricate drawings and paintings that new craft stories using traditional images and fashion.

Tulip Link Bracelet

Robin Waynee

Sterling Silver & 18K Gold Tulip link Bracelet with VS1 Diamonds (.50ctw)

Folding Braids 7

Wally Dion

Acrylic on paper

How did you get interested in creating art?

I grew up in a household where both parents were creative. My

father was a furniture maker and award winning wood sculptor. So the

interest was there for as long as I can remember. But what really got

me interested was when I met a guy who had his own little gallery

space and where he designed and created one-of-a-kind jewelry. I had

never seen anything like what he was doing. I asked if he would teach

me how to do it and he said yes!

Where/how did you learn your craft? Who helped you along the

way?

My husband gets sole credit for helping me along the way. I have

no official training. My education was through an apprenticeship that

turned into a partnership and 20+ years working and perfecting my skills.

Who are your biggest influences?

My husband’s work is inspiring. It’s organic and flowing. His

techniques and particular way of doing things sets his work apart from

everyone. I also find myself influenced by architecture. Not one

designer in particular though.

Was there a tradition or practice that was passed down to you?

Yes, my father taught me woodworking and basic jewelry production.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative practice?

I think growing up in a creative environment set me on my path. I

was artistic as a child and loved to draw. In jewelry design it’s

common to draw a design first and is often very helpful to have a

complete idea before creating. My father was a woodworker, sculptor,

jeweler, and photographer and being his favorite child, and he being

my favorite parent, I chose to hang out with him in his studio rather

than stay in the house and clean. I helped when and where I could. I

learned to read his mind and grab the tools he needed before he had to

ask for them. In all things, my dad always let me try my hand at what

he was doing and in that I learned a great deal of skills and

knowledge. Mostly, it peaked my interests in working with my hands and creating.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

That would have to be my Saul Bell Design Award pieces. It’s the

most prestigious - as well as the only international jewelry award -

any jeweler can win. And I won 3 years in a row, then again in 2020.

This competition has 2 rounds of judging. The judges are experts in

the jewelry world. For my work to have been judged by my peers and

contemporaries and having won with each entry is an honor and

achievement I had never dreamed of. My 2020 winning design is part of

this exhibition.

How has your career developed?

I started out with bare minimum knowledge of jewelry production

and have, so far, won every award a jewelry designer could win. I’ve

built long lasting relationships with collectors and have a well

established business.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

Being self-employed, I get to call my own hours and go for bike

rides when the weather is good. I love to cook. It’s my other passion

- in another life I was a chef, so I need lots of time for prep.

Living and working through this pandemic has been confirmation that

being able to have a home based work situation is one of the best

things about self employment. Quarantining life is not so far from our

everyday life.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

The flip side of the above answer. Being self-employed there’s no

guaranteed income or benefits. And you have to wear so many hats. I

can’t just create my art. I have to be a business person, sales

person, etc…

What do you want viewers to take away from your art?

My favorite feedback is “I have never seen anything like this.” I

have endeavored to be different with most things in life. I’m bored

with “trends” or what’s hot now… I’d rather stand out than conform to

the norm.

How does tradition and identity inform your work?

I have a diverse heritage. I am quite proud of who I am and whom

I come from. My work doesn’t identify with what “native jewelry” is

but it does reflect an intense commitment to precision, quality, wear

ability and uniqueness, attributes that could easily describe both

sides of my lineage.

How does your work comment on current social or political

issues?

It doesn’t. Or at least, I haven’t ventured there yet.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

FULL time, all the time. The creative process doesn’t rest.

What are some of the greatest challenges you face in making

your work?

I think the greatest challenge is to educate people on the

difference between mass production jewelry like in Zales and

my hand made one-of-a-kind jewelry. People do not understand the

skill, time, money, energy, TOOLS and equipment it takes to create

award winning pieces. If I only designed pieces, then sent them off to

China or Thailand to have made, I could offer it at low prices and

mass produce them. But I am hand picking center and accent stones. I’m

alloying 24k gold into 18k and rolling it into sheet form or drawing

down wire. Hand shaping, hand setting and finishing and photographing,

as well as selling my work. I. Do. It. All. One of the worst things is

how often Jewelry is passed over as being considered an art form. We

can be lumped into so many categories. But rarely does the creative

process be given the same status as paint, sculpture, pottery, etc…

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I would love to connect with the people of Michigan. I am from

there but my work is not well known in my home state.

How did you get interested in creating art?

I have been drawing and making art since childhood. I think some

people have a propensity towards creative endeavors or visual problem-solving.

Talk about your own art training.

My early art making was always supported by adults in the form of

art supplies and art instruction/lessons. Anyone and everyone I lived

with, or learned from supported and encouraged my art making. My

grade 8 teacher would allow me ‘alone art time’ in lieu of other

subjects. That year, I clocked in a lot of art time in my private

elementary school studio.

Who are your biggest influences?

My biggest influences are creative makers and practitioners who

are living examples of the person I want to be; people who took a

gamble and committed to a career, or practice, or project in-spite of

the odds or lack of support and interest. I look up to and respect

people who have devoted their lives to building and supporting a

cultural tradition. I appreciate crafts people especially, because

they contribute to a visual language that has been interrupted or

usurped by settler societies.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative practice?

I was raised in foster care so I think a lot of my story telling

incorporates a sense of optimism in people and ‘togetherness.’ Much of

my early life and the lives of people I love have been touched by

destruction; whether that takes the form of addiction, racial bigotry,

or violence. I envision a spectrum where creative and destructive

energies pull at each other. Without one, the other does not thrive.

Some of the most powerful and compelling artists and artworks I admire

are tied to dark and horrific events.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

I am proud of all of my works. Every piece is a masterpiece that

must stand the test of time.

How has your career developed?

My career as an artist has developed and strengthened slowly over

the years. In 2011, I stopped art making to attend graduate school in

Rhode Island. The experience was both difficult and challenging and

my production and creative directions fluctuated. It took several

years following graduate school to get back on track and find my

groove. Some days, I question the decision to attend grad school,

wondering if I should have completed it soon after my initial

bachelor’s degree, while other days I feel fortunate and

battle-hardened by the experience. Also, moving to the USA from Canada

has been difficult, both as an artist and Indigenous artist. Canada

has fewer people, so opportunities in the arts, as far as showing and

selling, are higher. The ratio of museums to artists in the USA must

be staggering, one million artists for every one museum maybe? Also,

the development of Indigenous art in Canada would be comparable to

Black art in America. In America, the number of Black artists,

scholars, critics, and writers is very high, going back several

generations. There is a strong tradition of Black art in America.

Today, that tradition is more evident; presidential portraits, major

museum collections, etc. Still, nowhere near the level of the white/

European art and art cannon, but it is a blip on the radar. As far as

Indigenous art in America, there is still work to be done in terms of

infiltrating and enriching the art world at large.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

I believe artists occupy a special place at the fringes of

society and their mission is to act as a mirror, reflecting our

potential as well as our failings. By some act of grace, I have lived

as an artist full time for many years. I often reflect upon the

unspoken exchange or debt that I owe for my privileged lifestyle.

Thus, I take seriously my art making and the topics I must engage with.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

Financial difficulties are ranked high on my list, when I am

experiencing doubt and difficulty.

What do you want a viewer to come away with?

I do not have any desired outcomes for viewers. I try to keep my

expectations low when it comes to: ‘what people find’ or ‘take away’

from my art. I am often surprised by people’s comments or

revelations. Imagine how boring an artwork would be if people read

exactly what I wanted them to read and nothing more?

How does tradition and identity inform your work?

Some of my work connects with specific Indigenous symbolism; the

eight point star/star blankets, or thunderbirds. I view Indigenous

art, or any culturally specific art cannon, as a fluid body that can

be added to and borrowed from. With my life’s work I hope to enhance

and add to the aesthetic language of Indigenous artists/people.

How does your work comment on current social or political issues?

Sometimes my work responds to an event or discourse affecting

myself or people I care about but other times I need to take a break

from political or socially motivated art. A recent group of paintings

featuring braided hair was my way of coping with the murder of an

Indigenous young person in my home community by a non-Indigenous

farmer. I chose to paint the back of a braided head as a reference to

the gunshot wound. Most viewers would not notice the bull’s eye,

impasto carved, into the canvas, but the message is there all the

same; in certain parts of the country it is still legal to execute trespassers.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I am a full time artist.

What are some of the greatest challenges you face in making

your work?

The greatest challenge I face as an artist is finding and

focusing on what matters to me. There are so many pressures in the

contemporary and traditional art worlds; it’s difficult to notice

their ever so slight pull or persuasions. However, the older I get

the less I care what people think, providing a sense of integrity and

freeing up energy.

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I would like everyday non-Indigenous people to look at this show

and understand Indigenous issues and peoples a little bit more.

Furthermore, I would hope that within the Indigenous art community,

craftspeople and artists continue to develop a unique and complex

visual language and engage one another in critical discourses.

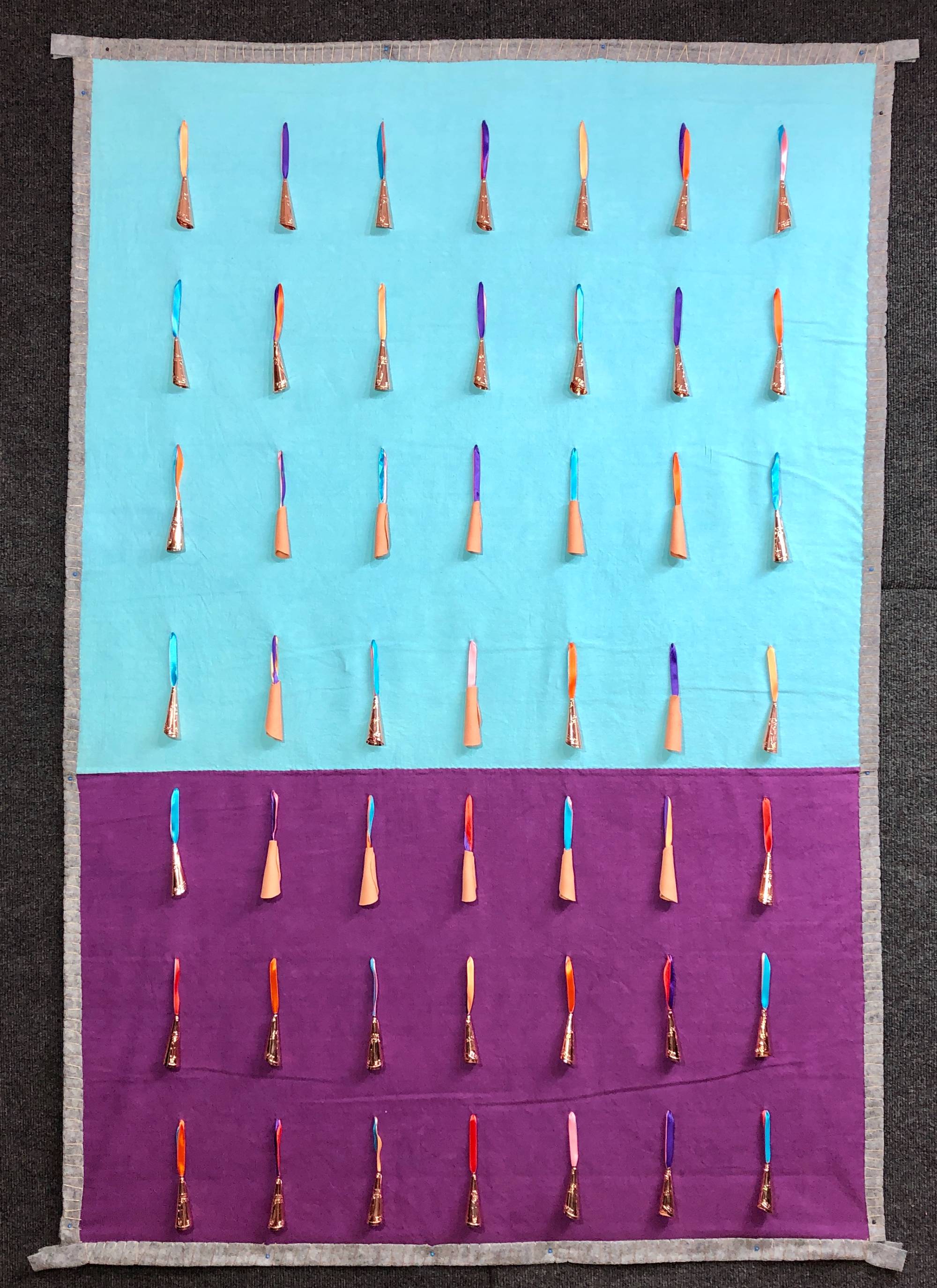

While ceramics are not traditional among the Potawatomi, Jason Wesaw has embraced the material to develop new forms and designs that speak to his heritage. Wesaw also draws, paints, and works in mixed media, with a focus on color shapes and geometry. The vibrantly colored paintings of Jonathan Thunder are decidedly post-Modern, blending mainstream pop-culture and cartooning with symbols of Native American identity and history to create new stories.

Mobbish Waboyan (Water Blanket)

Jason Wesaw

Hand dyed and hand sewn cloth with mixed media

Doctrine of Rediscovery

Jonathan Thunder

Acrylic on canvas

How did you get interested in creating art?

I was drawn to music, specifically the drums, from an early age.

My interest in creating rhythms paved a path into the visual arts,

always with a simplified approach to colors, symbols, and an affinity

for making work that shows the touch of the maker’s hand; a style

rooted in craft sensibilities, like the beautiful and functional

pieces made by my ancestors.

Where/how did you learn your craft? Who helped you along the way?

I recall my making my first ‘object’ in my early teens. A drum,

hollowed out from a log found in the woods, sanded and rubbed with raw

walnuts to give it a rich, dark tone, its double-sided rawhide heads

haphazardly tied together. I knew not how to make a drum and no

person taught me. But, I always felt I had help; the Spirits work in

that way. And ya know what?? That little drum sounded really good and

building it led me down the path of eventually making hundreds of

drums and becoming quite knowledgeable of our social and ceremonial

songs. This was the beginning of my becoming a maker. I’d likely be

considered an ‘outsider’ artist. Though I’ve studied at various

different places, I don’t hold a degree and I’m an art-school dropout.

Who are your biggest influences? Was there a tradition or

practice that was passed down to you?

There’s a long list of artists and elders who have helped shape

me. My Grandpa is one of my greatest mentors and inspirations. He’s a

maker too, and we’re always sharing ideas about how to do something

better and faster, allowing the work to inform us and evolve. The most

important tradition or practice that I hold close is the idea that we

keep good feelings in our heart and mind while we’re working. Even if

the inspiration or making the work itself is challenging, the creative

spirit is one that we should always appreciate as a gift from the Creator.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative practice?

My connection to the natural world and searching for balance in

the duality of life: simultaneously existing both physically and spiritually.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

My next piece!! Accolades and further opportunities are nice as

it helps keep the lights on and my ability to continue creating. But,

each piece and every show leads to the next idea, the newest creation,

and the deeper examination of what I’m trying really to communicate.

How has your career developed?

My career has developed haphazardly and somewhat slowly!! I make

work in a wide variety of mediums. I get into rhythms and patterns,

going where my interests lead, staving off boredom and trying to find

a cohesive language regardless of the material being used.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

The freedom, the exploration, the adventure, and the process of

taking ideas or inspirations and turning them into a tangible object.

I also enjoy collaboration and would like to make that a more integral

part of my future work.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

The business side of being an artist! Budgets, deadlines,

accounting for time spent on tertiary aspects of work like interviews,

shipping, making sales, etc., etc.

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

That the work speaks for me as an individual, a human being who

creates and prays and eats and enjoys life.

How does tradition and identity inform your work?

It informs my creative process from the perspective of place.

That the land, this place my ancestors have called home for many

hundreds and thousands of years, is who I am. The land has loved,

informed, and uniquely shaped us into the people we are: Bodwe’wadmi,

Keepers of the Fire, the original people of the St. Joseph River Valley.

Does your work comment on current social or political issues?

My work does not comment on current issues. It speaks

metaphorically about our identity as human beings and our place

amongst all of creation. That identity is formed through the land, our

culture, language, songs, ceremonies, and our acknowledgement of the Spirit.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I make art, I teach, and I work with the land. Along with

raising my kids, this is what I do in life.

What are some of the greatest challenges you face in making

your work?

I believe there are challenges every day. Some of the greatest I

face are motivation, finding clarity in the execution, balancing

between pushing the work to grow or letting it inform me as a person,

and maintaining focus.

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

For the viewers to see a collection of work that provides a broad

spectrum of styles, influences, and relevance as contemporary Tribal

people. That they may gain a deeper understanding of our continued

existence; one that is not merely surviving, but colorful and thriving.

How did you get interested in creating art?

As a kid I was fascinated by all forms of art. I drew on

everything. It was a great way to dive into a world where I could

bring things to life that interested me. My school councilor suggested

that I go to school for art, so I took a chance and listened to her

advice. At the Institute of American Indian Arts I found my people. I

studied painting, creative writing and dabbled in sculpture. When

making art, I feel like a shark in the water. I have worked at least a

dozen other jobs, but art is the only thing that I have stuck with.

Talk about your own art training. Who helped you along the way?

In 1999, I began to study painting at IAIA in Santa Fe, NM. My

instructor was Norman Akers, an Osage painter from Oklahoma. He is

known for large, surreal oil paintings with a lot of representation

imagery. I adopted many of his views on art. I wasn’t there for more

than a year or so. I stayed in Santa Fe and became a student of the

gallery scene for another couple of years after leaving IAIA. I moved

back to Minneapolis, where I was raised, and started developing a

style of my own, based on what I liked seeing in the painting world.

Who are your biggest influences?

I paid attention to work by surrealists, simply because of the

freedom of movement they expressed in the imagery created. But I also

like painters that use texture and brushwork to let a canvas speak for

itself. So artists like Dali and Kahlo influenced my thought process.

I like the portraiture that came out of the Renaissance. The dark

backdrops and accessories that accompanied the subject entertained my

eye and allowed me to create a narrative about the work. More

contemporary painters like TC Cannon, Tony Abeyta, and David Bradley

are southwestern painters that shaped my thoughts on texture, color

and composition. I would identify with low brow artists like Mark

Ryden, Ron English, and Chris Mars as well.

What personal experiences have shaped your creative practice?

I went back to college in 2002 to study film, visual effects and

animation. During that time I dove into making short stories and

vignettes come to life through CG, filming, and editing. During this

time I was still painting and had found representation that kept me in

exhibits and art fairs. My work started to merge with the concept that

each piece would be a story, or a vignette about something I wanted to

talk about. Since then I have worked in multiple mediums, including

traditional painting and digital artistry. On some projects I have

taken a completed canvas, scanned it, and animated the elements. I

also create short experimental or surreal films that I create like a

painting, adding a little here and there, until it looks done.

What work are you most proud of that you've created so far?

Each one after the last. I learn more with every project.

How has your career developed?

It cost me some shoe leather. After moving home from Santa Fe,

when I finally had enough paintings to show, I went from gallery to

gallery with a book of bad photographs of them. I got some help from

Juanita Espinoza at the Two Rivers gallery in South Minneapolis on

getting into some group exhibitions. Networking and keeping some new

work out there has led to one opportunity after the other.

What do you enjoy the most about being an artist?

Justifying my addiction to caffeine is working out pretty good

for me.

What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

When I leave the studio I shut off the lights and lock the door.

But I often find myself back there while doing the other things that

go into living a multifaceted life: family, friends, vacations,

grocery shopping, etc. I do what I love for work, so I get swept up in

it, and although I love it, it’s still work. So I have to force myself

to shut it off sometimes.

What do you want viewers to come away with?

This work is meant to be the first and possibly second comment in

a conversation about things that are of interest in my life, world,

and community. They are not meant to be the beginning and end of the

conversation, simply my two pennies.

How does tradition and identity inform your work?

I think about my identity as a citizen of the universe while

pondering imagery and meaning. The images are usually influenced by

what I see around or what I am interested at the time. I just painted

a birchbark canoe with hotrod flames going along the side. For me it’s

an intersection that I find myself at, being that water is a topic of

discussion when it comes to the oil industries practices in the

Midwest, but I am also a fan of muscle cars. If only the two could coexist.

How does your work comment on current social or political issues?

The social commentary in my work is often subtle. I’m of the mind

that if you tell someone what to think they will go in the other

direction. If you tell them how you think then you have a discussion

on your hands.

Do you make art full-time, or as you can?

I make art full time, but it’s a variety of personal undertakings

and commissions. The commissions are always something that I can get

behind, although I did make some random works for hire in the early

years. These days, if I’m working on it, it’s probably something that

I care about. I get hired to make animations, murals, logo design,

portraits, large scale installations, small installations, and when

I’m not doing that you can find me spending days in front of a canvas.

This year I received a generous grant from the Pollock-Krasner

Foundation based on my painting portfolio. I’m grateful for that

award, being a full time artist can be disorienting if you try to make

sense of it too much, and the award was like a needle on a compass

saying “keep on this path, you’re going the right way.”

What are some of the greatest challenges you face in making

your work?

Emails and contracts are something I wish took less of my studio

time. I like to joke and say “the hardest part about being a working

artist is finding the time to make the work.”

What outcomes would you like to see from this show?

I’m just grateful to be invited to show with some rad artists.

Research Tools

This exhibition engages themes related to Native American studies, social justice, identity and more. The GVSU Library subject guides listed below and the databases list under "Additional Resources" help you find articles related to these themes. Download the Learning Guide (right) for more information about these themes.

Subject Guides

- Art & Design

- Environment & Sustainability

- History

- Human Rights

- Indigenous People, Native American Studies*

*We recommend this subject guide as the most complete resource on Indigenous history, culture, issues, and more. Many of the resources listed below are taken directly from this guide.

Recommended Reading

Check out the following GVSU Library books and articles covering key themes and other content related to the exhibition. Or use the Libraries Catalog to find more books and articles. Visit the Michigan tab on the Libraries' Native Americans subject guide for a long list of specifically Michigan and Midwestern resources.

Thank you to Amber Dierking and Kim Ranger with the GVSU Libraries for their guidance in compiling this list.

-

(electronic) Native

Studies Keywords edited by Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Andrea

Smith, and Michelle H. Raheja, 2015

Explores 8 concepts in Native studies and the words commonly used to describe them: sovereignty, land, indigeneity, nation, blood, tradition, colonialism, and indigenous knowledge. Each section includes three or four essays and provides definitions, meanings, and significance to the concept, lending a historical, social, and political context. Here are the foundational concepts of Native American studies, offering multiple perspectives and opening a critical new conversation. -

(electronic) Handbook

of Indigenous Education, edited by Elizabeth Ann McKinley

and Linda Tuhiwai Smith, 2019

This book is a state-of-the-art reference work that defines and frames the state of thinking, research and practice in indigenous education, bringing together a wide range of educational topics including early childhood education, educational governance, teacher education, curriculum, pedagogy, educational psychology, etc.

-

(streaming) First

Peoples: Americas by the Public Broadcasting Service, 2015

As early humans spread out across the world, their toughest challenge was colonizing the Americas - because a huge ice sheet blocked the route. It has long been thought that the pioneers, known as Clovis people, arrived about 13,000 years ago, but an underwater discovery in Mexico suggests people arrived earlier than previously thought - and by boat, not on foot. How closely related were these First Americans to today's Native Americans? It's a controversial matter, focused on Kennewick Man. Few other skeletons engender such strong feelings. -

(streaming) Our

Fires Still Burn: The Native American Experience by Visions

(Firm), 2013

This compelling one hour documentary invites viewers into the lives of contemporary Native Americans. It dispels the myth that American Indians have disappeared from the American horizon, and reveals how they continue to persist, heal from the past, confront the challenges of today, keep their culture alive, and make significant contributions to society. Their experiences will deeply touch both Natives and non-Natives and help build bridges of understanding, respect, and communication. -

(print) Native

Universe: Voices of Indian America edited by Gerald McMaster

and Clifford E. Trafzer, 2004

Published in conjunction with the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian's new building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., Native Universe offers readers a deeper understanding of Native philosophies, histories, and identities. Featuring essays by such distinguished Native Americans as Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux), Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee), Victor Montejo (Maya), and many more, Native Universe reveals the rich heritage and true diversity of the Indian Americas. -

(print) Voice

on the Water: Great Lakes Native America Now edited by Grace

Chaillier and Rebecca Tavernini, 2011

These are the stories, poems and images that echo the lives of contemporary American Indians living in Michigan. The contributors' narratives and art address themes of the land, the lakes, family, the search for center, ideas of time and the past, communalism and our Native communities on and off reservation homelands, along with story-telling, Indian education, the Michigan urban Indian experience, ceremony and ritual, persistence of traditional arts and lifeways, and new cultural ways of being.

-

(electronic) Documents

of Native American Political Development: 1500s to 1933 by

David E. Wilkins

The arrival of European and Euro-American colonizers in the Americas brought physical attacks against Native tribes and against the sovereignty of these nations. The political structure and development of Native peoples, and the effect of American domination on sovereignty have been greatly neglected. This book contains a variety of primary source and other documents -- traditional accounts, tribal constitutions, legal codes, business councils, rules and regulations, BIA agents reports, congressional discourse, intertribal compacts--written both by Natives from many different nations and some non-Natives, that reflect how indigenous peoples continued to exercise a significant measure of self-determination. Brief introductory essays place documents within context. -

(electronic) Critically

Sovereign: Indigenous Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist

Studies by Joanne Barker, 2017

Gender, sexuality, and feminism work as co-productive forces of Native American and Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination, and epistemology, along with the production of colonial space, the biopolitics of "Indianness," and the collisions and collusions between queer theory and colonialism within Indigenous studies. Diné marriage and sexuality, Iñupiat people's changing conceptions of masculinity, Hawai'i's same-sex marriage bill, and stories of Indigenous women falling in love with non-human beings such as animals, plants, and stars.

-

(print) Decolonizing

Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples by Linda

Tuhiwai Smith, 1999

From the vantage point of the colonized, the term 'research' is inextricably linked with European colonialism; the way in which scientific research has been implicated in the worst excesses of imperialism remains a powerful remembered history for many of the world's colonized peoples. -

(print) Comparative

Indigeneities of the Américas: Toward a Hemispheric Approach

edited by M. Bianet Castellanos, Lourdes Gutiérrez Nájera, and

Arturo J. Aldama, 2012

The effects of colonization on the Indigenous peoples of the Américas over the past 500 years have varied greatly. So too have the forms of resistance, resilience, and sovereignty. Understanding the commonalities will help articulate new ways of pursuing critical Indigenous studies, via themes like indigenísmo, mestizaje, migration, displacement, autonomy, sovereignty, borders, spirituality, and healing across the Américas. Indigenous and mestiza/o peoples resist state and imperial attempts to erase, repress, circumscribe, and assimilate them.

-

(print) Hearts

of Our People: Native Women Artists by Jill Ahlberg Yohe,

Teri Greeves; editor, Laura Silver; foreword by Kaywin Feldman, 2019

Women have long been the creative force behind Native American art, yet their individual contributions have been largely unrecognized, instead of treated as anonymous representations of entire cultures. 'Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists' explores the artistic achievements of Native women and establishes their rightful place in the art world. This lavishly illustrated book, a companion to the landmark exhibition, includes works of art from antiquity to the present, made in a variety of media from textiles and beadwork to video and digital arts. It showcases more than 115 artists from the United States and Canada, spanning over one thousand years, to reveal the ingenuity and innovation that have always been foundational to the art of Native women. -

(print) Shapeshifting:

Transformations in Native American Art by Karen Kramer

Russell; with Janet Catherine Berlo [and others]; and

contributions by Kathleen Ash-Milby [and others], 2012

Public perception of Native American art and culture has often been derived from misunderstandings and misinterpretations, and from images promulgated by popular culture. Typically, Native Americans are grouped as a whole and their art and culture considered part of the past rather than widely present. This work challenges these assumptions by focusing on the objects as art rather than cultural or anthropological artifacts and on the multivalent creativity of Native American artists. The approach highlights the inventive contemporaneity that existed in all periods and continues today. More than 75 works in a wide range of media and scale are organized into four thematic groups: changing, expanding the imagination; knowing, expressing worldview; locating, exploring identity and place; and voicing, engaging the individual. The result is a paradigm shift in understanding Native American art. -

(electronic)

Injichaag: My Soul in Story by Rene Meshake and Kim

Anderson, 2019

This book shares the life story of Anishinaabe artist Rene Meshake in stories, poetry, and Anishinaabemowin "word bundles" that serve as a dictionary of Ojibwe poetics. Meshake was born in the railway town of Nakina in northwestern Ontario in 1948, and spent his early years living off-reserve with his grandmother in a matriarchal land-based community he calls Pagwashing. He was raised through his grandmother's "bush university," periodically attending Indian day school, but at the age of ten Rene was scooped into the Indian residential school system, where he suffered sexual abuse as well as the loss of language and connection to family and community. This residential school experience was lifechanging, as it suffocated his artistic expression and resulted in decades of struggle and healing. Now in his twenty-eighth year of sobriety, Rene is a successful multidisciplinary artist, musician and writer. Meshake's artistic vision and poetic lens provide a unique telling of a story of colonization and recovery. -

(print) Art for an Undivided Earth: the American Indian

Movement Generation by Jessica L. Horton, 2017

Jessica L. Horton reveals how the spatial philosophies underlying the American Indian Movement (AIM) were refigured by a generation of artists searching for new places to stand. Upending the assumption that Jimmie Durham, James Luna, Kay WalkingStick, Robert Houle, and others were primarily concerned with identity politics, she joins them in remapping the coordinates of a widely shared yet deeply contested modernity that is defined in great part by the colonization of the Americas. She follows their installations, performances, and paintings across the ocean and back in time, as they retrace the paths of Native diplomats, scholars, performers, and objects in Europe after 1492. Along the way, Horton intervenes in a range of theories about global modernisms, Native American sovereignty, racial difference, archival logic, artistic itinerancy, and new materialisms. Writing in creative dialogue with contemporary artists, she builds a picture of a spatially, temporally, and materially interconnected world-an undivided earth.

-

(print) Tracks

by Louise Erdrich

Told in the alternating voices of a wise Chippewa Indian leader, and a young, embittered mixed-blood woman, the novel chronicles the drama of daily lives overshadowed by the clash of cultures and mythologies. -

(print) Love

Medicine by Louise Erdrich

A story of the intertwined fates of the Kashpaws and the Lamartines near a North Dakota reservation from 1934 to 1984. -

(electronic and print) Blue

Ravens by Gerald Vizenor

After serving in the American Expeditionary Forces, two brothers from the Anishinaabe culture return to the White Earth Reservation where they grew up. They eventually leave for a second time to live in Paris where they lead successful and creative lives. With a spirited sense of "chance, totemic connections, and the tricky stories of our natural transience in the world," Vizenor creates an expression of presence commonly denied Native Americans. Blue Ravens is a story of courage in poverty and war, a human story of art and literature from a recognized master of the postwar American novel and one of the most original and outspoken Native voices writing today. Check for the online reader's companion at blueravens.site.wesleyan.edu.

Events & Activities

Join us for a virtual event co-sponsored by the GVSU Office of Multicultural Affairs and the Muskegon Museum of Art. Shirley Brauker, Jason Quigno, and Jonathan Thunder will join Dylan A.T. Miner, Director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at Michigan State University, in conversation about their artwork, as well as their creative processes and contemporary issues in the indigenous community. Open to all, RSVP required.

Personalized virtual tours or classroom visits are available upon request! Email User Experience & Learning Manager, Amanda Rainey, to set-up a virtual tour or visit for your class; [email protected]

Additional Resources

Films & Exhibitions

- Levi Rickert: Standing Rock, Photographs of an Indigenous Movement at the Muskegon Museum of Art

- “No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography at the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

- Online Exhibitions at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

History, Land, & Language

- Native American Oral Histories at the Grand Rapids Public Museum

- MSU's Native American Studies Research Guide

- Our home on Native land: Anishinabewaki: This map includes the Ojibwe, Odawa, and overall Anishinaabe traditional lands and migrations. Native Land Digital is a Canadian, Indigenous-led, not-for-profit organization.

- First Nation Seeker: First Nations across North America at time of first contact: linguistically based

- Anishinaabemdaa: Anishinaabe language lessons, stories, jokes, culture & history lessons in Anishinaabemowin by Kenny Pheasant

- Native American Indian Studies, A Note on Names by by Peter d'Errico, Legal Studies Department, University of Massachusetts

Get Involved On Campus

- NASA: Native American Student Association

- Gi-gikinomaage-min Project: Defend Our History, Unlock Your Spirit - Gi-gikinomaage-min: gee-gi-ki-no-ma-gay-min. Translated from Anishinaabemowin, the original language of this area, Gi-gikinomaage-min means "We are all teachers." This is the name our project team choose to convey to the Native American community that through our stories and experiences, we are all teachers to someone. As we share those stories, we are allowing for our next generations to experience the past.

More from the GVSU Art Gallery & Permanent Collection

Additional Artworks from the GVSU Art Collection

Use Art in the Classroom

Location

January 11, 2021 - February 26, 2021

Performing Arts Center Gallery

Performing Arts Center

1 Campus Dr.

Allendale, MI 49401

Hours:

Monday 1:00 p.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Wednesday 1:00 p.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Thursday 1:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m.

Friday 1:00 p.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Contact

For special accommodation, please call:

(616) 331-3638

For exhibition details and media inquires, please email:

Joel Zwart, Curator of Exhibitions

[email protected]

For learning and engagement opportunities, please email [email protected].

[1611025156].jpg)